On Being A TV Bystander In The Age Of #GameOfThrones

From That Episode of Game of Thrones, to That Season of Arrested Development; what it feels like when a show we don't watch takes over our Facebook feed.

So, I haven’t yet watched it myself, but I hear that something massively shocking and traumatic happens in this week’s Game of Thrones. (CoughIpredicteditbackinAprilcough.) Even if you don’t care about this plot twist, you simply cannot escape the general angst about it.

“I’m literally shaking from the Game of Thrones episode,” tweeted someone I follow. “I’m never getting over it.”

“It’s been on my mind all night since I watched the last episode!” said a friend on Facebook.

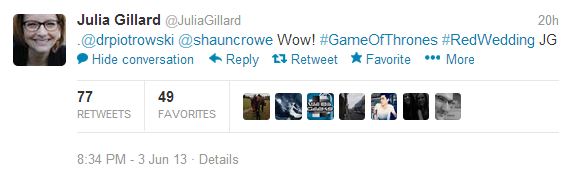

Junkee follows Game of Thrones, which is lucky for me because it’s also one of my favourite shows. Me, and most of Australia. Even Julia Gillard is into it.

But people who don’t watch it can find other people’s obsession annoying and alienating.

I felt the same about all that to-do over Arrested Development season four — I stopped watching Arrested Development halfway through season two. But the first time I remember feeling actively left out of post-broadcast TV fandom was Battlestar Galactica. My brother raved about it. My friends tweeted about it. It sounded interesting. But I never watched it, and still haven’t to this day.

When hyper-mediated fandom takes hold, a TV series is elevated above mere entertainment to a pedestal of social significance. Often, its creator is venerated as a visionary genius. It’s easy for fans to assume everyone else is a fan, too. We lose ourselves in the viewing peaks and troughs of seasonal schedules or DVD releases, thoughtlessly trampling the joy of discovery for others in our haste to consume new material. And we presume anyone who doesn’t share our passion is ‘missing out’.

Perhaps we should think more about what it means and how it feels to not-watch – to be a TV bystander.

You Need To Make Choices:

Life is short, and leisure time precious. Now that we have so much great culture competing for our attention, we have to be strategic. We can’t possibly consume it all, or we’ll end up like Cate Blanchett at the end of Kingdom of the Crystal Skull.

And even the stuff we do consume sometimes doesn’t always sink in.

The Huffington Post recently asked members of the public, who claimed to have read The Great Gatsby, to explain the novel’s plot. Some were stumped when asked to name the hero.

Linda Holmes, of NPR’s culture blog Monkey See, says we respond to pop culture’s dizzying plenitude with two strategies: to cull, and to surrender. To cull is usually to react against something: to make a blanket rule that we’re not interested in certain things. You might go “I don’t like crime procedurals” or “Australian TV is crap.” And in scrambling to avoid being accused of snobbery, you might even end up bizarrely suggesting that TV snobs hate critically acclaimed series.

A strategy of surrender, on the other hand, means making peace with abundance. You say to yourself, in Holmes’s words: “I might be missing something great, but I can’t have everything.”

There are heaps of beloved shows I’ve never seen. Deadwood. The Wire. Boardwalk Empire. The Walking Dead. House of Cards. But the pleasures they offer haven’t evaporated with their original, zeitgeist-y moments. They are still ripe with deferred enjoyment. Knowing I could watch them if I chose – but am choosing not to right now – is comforting, rather than bewildering.

Bystanding Isn’t Engaged — But Nor Is It Totally Detached:

Witnessing online TV discussion without watching the shows feels like taking your car through a mechanised car wash. You’re watching the rollers descend and the foam cascade over your windscreen, hearing the spraying and thumping and squeaking and the whirr of the machinery making it all happening, and all the while you’re sitting quietly, not doing anything, feeling oddly remote from the tempest.

Through online osmosis — tweets, Facebook reviews, links to recaps and interviews and analyses — I get to know the characters in shows I don’t watch; the showrunners, cast and other personnel. The mythology a show acquires on its journey through the peristaltic TV network system, from initial pitch to triumphant finale or shameful final axing. Even the following that a show acquires, and the tone and pitch of its online buzz, are informative.

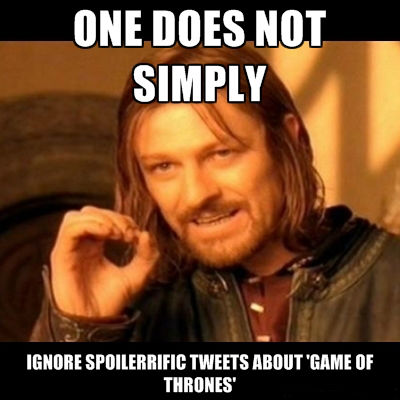

Most of all, I absorb key ‘moments’ in the narrative without understanding their original context within the episode. The screencap and animated GIF (HARD G FOREVZ YO!) are especially good at enshrining characters’ gestures, glances, expressions, or key lines of dialogue. These are clearly shibboleths: viewing comprehension tests in which insiders will LOL, share, or knowingly mutate the meme. Outsiders will remain silent and confused. Bystanders half-get the jokes, and have to make tough calls about whether to join in.

The ever-controversial Devin Faraci suggests it’s your responsibility to avoid spoilers: “We can’t wait around for you forever.” Yet to deliberately avoid social media out of spoiler paranoia actually requires a deep engagement in a show. Bystanders are semi-detached. They value social connectivity, and they are not about to evacuate shared online spaces simply because Faraci deems they’re “not taking part in the full, wonderful ritual of watching a great TV show”.

Bystanders’ experiences are partial, but possibly also wonderful.

A Bystander Needn’t Be A Hater:

My friends were rabidly into Buffy the Vampire Slayer. I watched a few episodes and didn’t warm to the smarmy characters and rib-elbowingly obvious themes. But the fact that everyone else treated Buffy as self-evidently brilliant made my mere disenchantment fester into outright hatred. This reached a peak in 2003, when an academic pop music conference I was attending was co-hosted with a ‘Buffy studies’ conference. Oh man, it filled me with vitriol that learned people could confuse fandom with research.

When Girls first became a phenomenon, I was ready to hate it in a Buffy-ish way (ie, because people wholeheartedly adored it and worshipped Lena Dunham as a genius), but then watched maybe six episodes of the first season and was like, “I get it now.” Not that I finished that season, or followed the second one. Yet it’s been fascinating to ride the series’ ebbs and flows, to watch people getting buffeted by the shocking plots without actually watching them myself. (I’ve also read enough commentary about Girls that I can carry on a perfectly articulate conversation about it.)

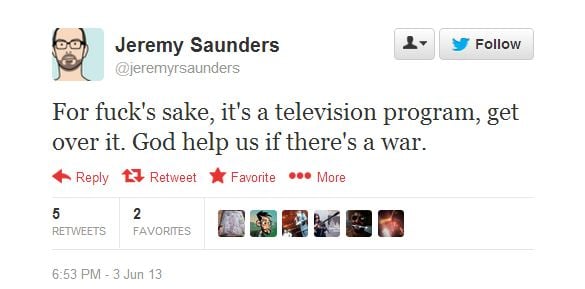

Yet the one-eyed raves and ‘me-first’ culture of flaunting plots and jokes can become wearying and obnoxious – actually deterring me from wanting to step up from bystanding to actually watching. Bystanders can then succumb to their own snarky temptations. This sentiment about Game of Thrones was retweeted into my stream yesterday:

“The ‘entire season in one go’ idea not only fragments the conversation but reduces it to a trivial dick measuring contest as all people can reasonably say is how many episodes they have seen,” my film-critic buddy Rich said in a recent Facebook conversation about Arrested Development. “Disappointingly reductive – and that’s the last thing the already simplistic Twitterverse needs.”

Another reviewer friend, Glenn, added: “The tweets I have been seeing all day are incredibly frustrating because, in a complete opposite reaction to what it’s meant to be doing, it’s making me not want to watch it. For now, anyway.”

At its worst, bystanding can feel like observing the nonsensical Caucus-race of Alice in Wonderland, in which participants start and stop running whenever and wherever they like. Then they all crowd around, asking, “But who has won?” Sometimes, the answer seems like: “Nobody.”

—

Mel Campbell is a freelance journalist and cultural critic. She is the founding editor of online pop-culture magazine The Enthusiast and the national film editor of the Thousands network of city guides.

Illustration by Matt Roden.