No, I Won’t Stop Being Angry About Oppression (And That’s No Reason To Shut Me Down)

"In the social and political environment we’re in, the way we talk, listen and discuss things matters."

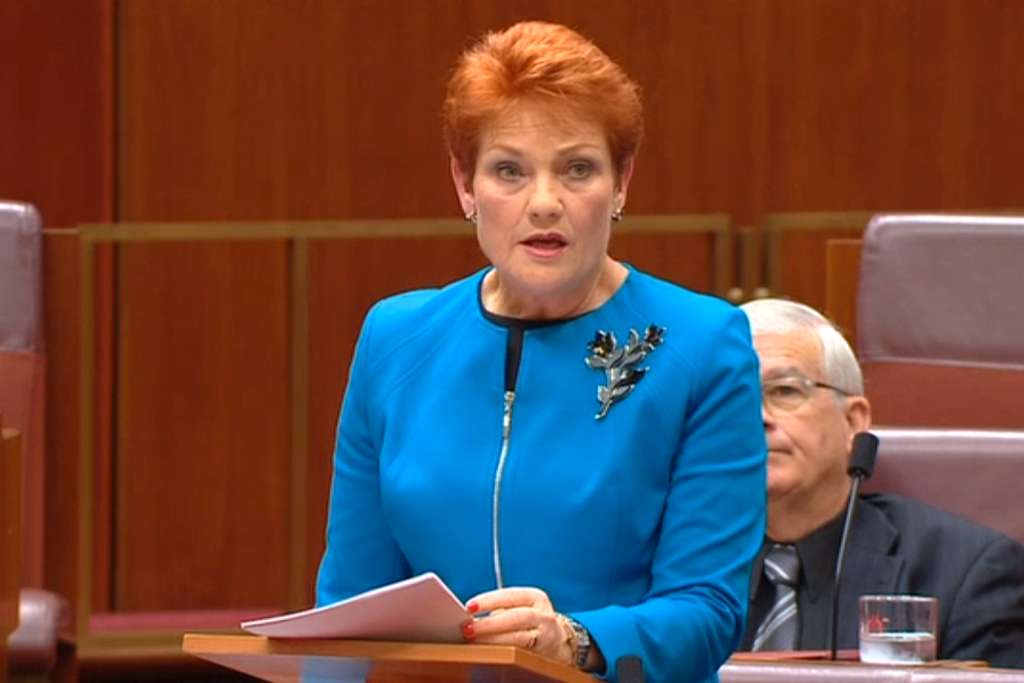

Since the federal election last year saw the re-introduction of Pauline Hanson in parliament — and all over our television screens — and the US election a few months later resulted in Donald Trump rising to the White House after a hate-filled campaign against Muslims and Mexicans, there’s been a lot of discussion about what the hell is going on.

If your Facebook or Twitter feed look anything like mine, there’s been a flood of ‘I Can’t Believe It’s Happening’-style posts in response to some of the hateful stuff we’ve seen recently. Trump’s executive orders have attempted to place immigration bans on people from certain Muslim majority countries. Closer to home, engineer/author/activist Yassmin Abdel-Magied last month had to defend her religion on live television in the face of misinformed attacks by Senator Jacquie Lambie, then face intense abuse and online petitions by ‘alt-right’ groups calling for her to be sacked from her job.

A lot of white liberals have expressed shock through all this, after legitimately failing to see what systemic racism and growing Islamophobia in the Western world could result in. It’s likely it never directly impacted them. There are a lot of people just waking up to what the world is like when you are either an immigrant, person of colour, Indigenous, Muslim, any other religious minority, LGBTIQ, not able-bodied or a combination of the above.

While that’s undoubtedly a good thing, what’s less great is the way in which some now ‘woke’ progressives have criticised the tone in which marginalised people discuss the legitimate hurt and anger they are feeling.

People are criticising those who applauded when a Nazi got punched, arguing we should instead be engaging in a dialogue with white supremacists to understand their beliefs. There are reports of white feminists scolding women of colour at the Women’s March on Washington for holding signs that said ‘Hold White Women Accountable’ and telling them they were being exclusionary. There are growing calls for those most directly at risk of harm to ‘unite’ and ‘practice understanding’ when there’s every reason to be mad about what the world we live in is turning into.

These calls are a form of tone policing, and quite frankly, they suck.

What Is Tone Policing?

Tone policing is essentially when someone criticises an argument by a marginalised or impacted person by focusing on the emotion behind the message (and whether this emotion is ‘correct’), rather than the message itself. Being tone policed while speaking out about an issue that directly impacts you is really derailing. It’s been done to me by people who think they care and want to help, and it’s left me feeling hurt and unheard.

I arrived in Australia, with my family, in 1995. The year after we migrated here, Pauline Hanson gave her maiden speech to the House of Representatives in which she built on the abhorrent statements she had made about Aboriginal communities, and said that Australia was being “swamped by Asians”. Hanson’s rhetoric was filled with hate and disdain toward Asian migrants who, according to her, weren’t welcome in Australia. I was one of those Asians she hated.

So, when Hanson left parliament and the main Australian political arena, it came as a relief to me. I thought it would be easier to build a life in Australia with my family without a voice in parliament reminding me of how I wasn’t welcome. But, while Hanson had left the house, the reminders of being unwelcome remained.

It can come as a surprise to some friends, but I’ve been yelled at on public transport. I’ve been that passenger you have seen on viral YouTube videos that is being harassed by someone with racist stereotypes about Indians; I’ve been told migrants are stealing all ‘our’ jobs and told to go back to where I came from. This was all while I was trying to make my usual commute to work or home from school. And it’s about as traumatic and horrifying as you’d imagine. It fills you with shame and then anger.

So when numerous people on my Facebook feed posted memes about Hanson’s politics or Pauline Pantsdown videos with jokes about ‘90s nostalgia, it didn’t feel funny to me. I responded to this humour — about the re-election of a woman who had filled many of my childhood years with fear — with a Facebook post. I wrote about how non-PoCs or non-Muslims sharing Hanson’s views as something to laugh at, ignores the very real impact her views have on minorities — people who know that Hanson represented real thoughts of real people with very real prejudices.

I was upset because a lot of the people sharing jokes about Hanson failed to see the legitimate danger of normalising her as a joke.

Next came the private messages, from self-described ‘well-meaning friends’ reminding me (in case I’d forgotten) that we lived in tough times, where there were a lot of people feeling alienated, where recent polls showed that 50 percent of Australians would support a Muslim ban and my anger could alienate these people further. I was told I should take a more conciliatory tone to reach out. If I continued to be confronting, they argued, people just couldn’t side with me.

Folks — I give you tone policing 101. My well-meaning FB friends were demanding a higher standard of those who are oppressed than those doing the oppressing. And if I wasn’t willing to meet that standard, they wouldn’t listen.

Remember when Nicki Minaj called out the VMAs saying she wasn’t nominated for Video of the Year for ‘Anaconda’ because she wasn’t a skinny white woman, and Miley Cyrus said she couldn’t agree with her because of the tone she took? Or maybe you remember when Waleed Aly took a break from doing legitimately great things for the #sendforgivenessviral campaign? It called on Muslims in Australia to forgive Sonia Kruger for publicly advocating a Muslim ban, and asked them to understand why people might be fearful and Islamophobic towards them.

This is tone policing. It asks ‘us’ to be more reasonable, objective or rational — to keep the emotions out of it.

Who’s Being Reasonable?

All this really comes unstuck when you ask what behaviour is, or should be, considered ‘reasonable’. The people who decide what is acceptable and rational are the people that have the privilege of stepping back from a conversation when it gets too ‘heated’. In most cases, they are not directly impacted by it. It’s a luxury that those who come off as ‘angry’ cannot afford.

In the case of the Facebook post about Hanson, I was told to be calmer by people who didn’t have to deal with the first-hand impacts of the racist views I was angry about. They could turn off their phone or laptop and disengage from Hanson being re-elected, but for me it was a reminder of the daily experience I had carried as a migrant in Australia over the past 20 years. They could afford to not be enraged about it because they had an escape.

You might dismiss all this as merely the view of someone who wants to be angry without any tempering of that by people who want to be calm. But in the social and political environment we’re in, the way we talk, listen and discuss things matters. Tone policing is harmful to this discussion.

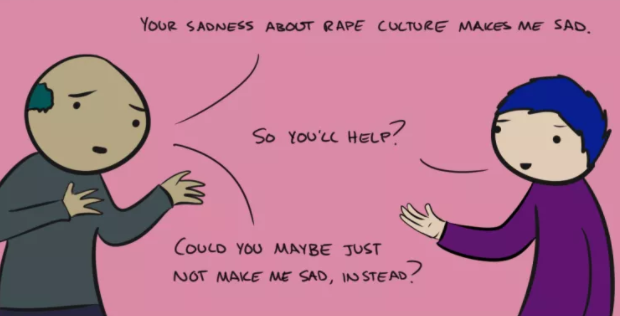

Comic panel via Robot Hugs. Check out the full piece here.

What’s Wrong With Tone Policing?

Tone policing assumes that legitimate discussions can’t involve emotions. Those who attack anger as a helpful emotion to fuel social change believe that the feeling makes people feel uncomfortable, and by being angry you’re disengaging people who you need on your side. Instead, they advocate for reaching out with compassion and empathy to those who may have harmful views and to transform them with kindness.

This is a well and good approach for some. But to demand marginalised voices empathise with those who hold oppressive views against them is burdensome. It’s asking people who are already harmed, to push past their emotions to do more to be understood. In the wake of Trump’s election, we saw calls for PoC, black and Muslim voters to understand the ‘white working class’. When in reality, a lot of the white voters who think they’re getting left behind are in fact doing just fine. The people we’re asked to reach out to are so often not disenfranchised, but instead just uncomfortable about seeing their own privilege.

Tone policing prioritises people’s comfort over understanding why someone else might be hurting, even if it makes you feel a little uncomfortable while doing so. This is what’s saddest to me about the whole thing. It indicates conditional support. It tells me that you’re only going to get behind me if I express myself in a way that isn’t too threatening to your idea of how I should talk and feel. And if I don’t, you’ll switch off. That sucks, mainly because it continues to embody the cis/white supremacist/hetero patriarchy that got us here in the first place, and what quite frankly we should all be working towards smashing down.

Comic panel via Robot Hugs. Check out the full piece here.

So, next time you try to tell a marginalised person to take a calmer tone when speaking of their experience, think about if you’re tone policing. Ask whether your demand for a less confronting approach is derailing the actual conversation that needs to happen. And then, don’t do it.

—

Kamna Muddagouni is a writer and podcaster at Can U Not? based in Melbourne. She tweets at @kamnamm.