Nine Most Effective Uses Of Profanity In Film And TV

"You were f**king Tessa Campanelli?", and other legendary exclamations.

Last week, news broke that Martin Scorsese’s new film The Wolf Of Wall Street set an all-time record for the use of F-bombs on the big screen — 506 (the previous title holder was Spike Lee’s Summer Of Sam, with 435). But there’s a right and a wrong way to use profanity on screen. It’s a powerful garnish that’s often mistaken for a necessary ingredient — something that should be native to a character’s personality and not driven by the writer’s need to project ‘badness’ or make more of a limp emotional moment. It’s fine for Tommy from Goodfellas (1990) or Mr Blonde in Reservoir Dogs (1992) to salt every sentence with the four-letter word, as they wouldn’t know it any other way, but if a middle-class protagonist is throwing a tantrum over an unrewarding career, no over-articulated ‘fuck’ is going to make us give any more of a… fuck.

That being said, nothing dots an ‘i’ and crosses a ‘t’ like a potty-mouth put to professional use. Here are a few of the most effective… (And apologies in advance, but “Yippee-ki-yay, motherfucker!” and “I’ve had it with these motherfucking snakes on this motherfucking plane!” will not be included in this list).

–

Dog Day Afternoon (1975)

Sonny: Kiss me.

Det. Sgt. Eugene Moretti: What?

Sonny: Kiss me. When I’m being fucked, I like to get kissed a lot.

A ground-breaking film in its day, Dog Day took a massively underrepresented protagonist (a gay man), treated him like any other heterosexual hero, and told one hell of a hostage film in the process. It captured the era’s prevailing sentiment: inquisitiveness, frustration and the need for societal upheaval — and provided one of the most distinct motivations for a bank robbery in the form of payment for a sex-change operation. Sonny’s open defense of he and Leon’s relationship and of his own sexuality is as powerful today as it was upon its release, and is typified by this classic exchange between he and the detective on the scene (see 1:17).

–

Glengarry Glen Ross (1992)

Blake: I made $970,000 last year. How much you make? You see, pal, that’s who I am. And you’re nothing. Nice guy? I don’t give a shit. Good father? Fuck you — go home and play with your kids. You wanna work here? Close! You think this is abuse? You think this is abuse, you cocksucker? You can’t take this — how can you take the abuse you get on a sit?!

Perhaps the most testosterone-filled film ever made to not include a single car chase or fight scene (made even more bizarre by the fact that it’s a film about telemarketing), David Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross is a happy-swearer’s heaven. Al Pacino, Jack Lemmon, Kevin Spacey, Ed Harris and Alan Arkin F the hell out of every conversation in a way that highlights the desperation and impotence of these commission-driven men, but it’s bit-parter Alec Baldwin that steals the show with an anti-pep talk that may as well have been spoken by his scrotum. The monologue is a thing of beauty and should be experienced in its entirety, but here’s a taste of what to expect (see 2:55).

–

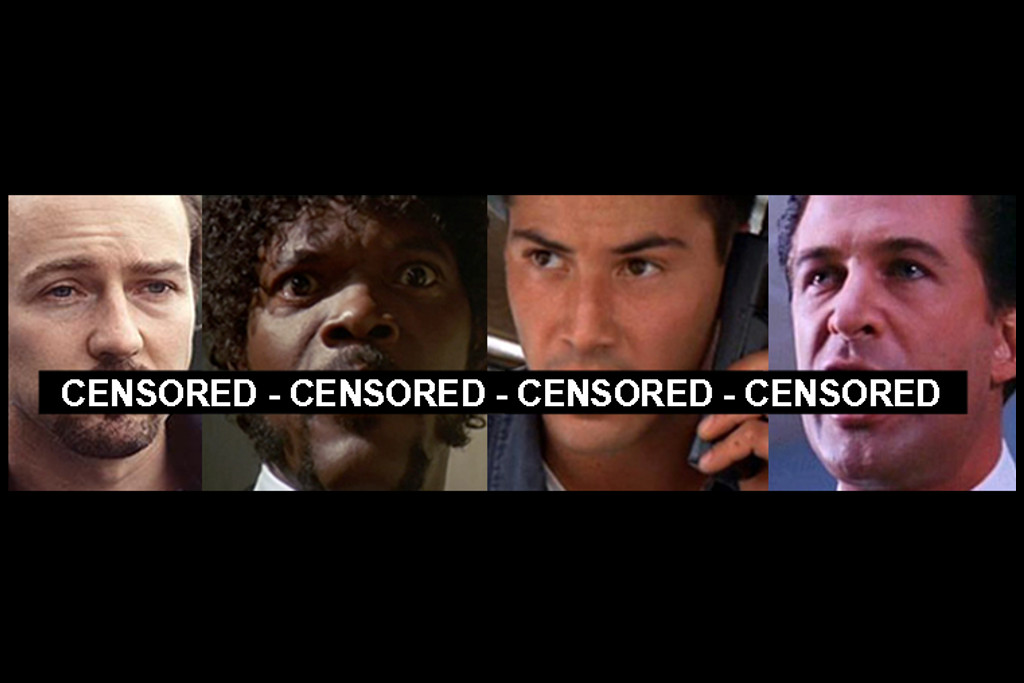

Pulp Fiction (1994)

Jules: You sendin’ The Wolf?

Marsellus: You feel better, motherfucker?

Jules: Shit negro, that’s all you had to say!

It was difficult to decide which Tarantino film to include in this list, and even more difficult to choose a particular moment. Quentin is the rare screenwriter that pours profanity into every exchange, almost until its use becomes a character in itself. While many debate its necessity, the fact of the matter is that his films wouldn’t be the same without it. In Pulp Fiction, there are handfuls of examples where a sentence is made more effective by a risque word (anything related to In-N-Out Burger/mayonnaise in Europe/foot massages), but a favourite would have to be this exchange between Samuel L. Jackson and Ving Rhames (see 0:35).

–

The Usual Suspects (1995)

Fred Fenster: Hand me the keys, you cocksucker.

Cop: In English, please.

Fred Fenster: Excuse me?

Cop: In English.

Fred Fenster: Hand me the fucking keys, you cocksucker, what the fuck?

It’s always difficult to revisit a film from your youth for fear it’ll lose its effect (see: Requiem For A Dream, Run Lola Run), so for some time I’ve avoided popping this twisty caper into the DVD player. But one thing’s for sure: Benicio Del Toro’s casual approach to a police line-up is timeless. Perhaps one of the most subtle uses of the F-word ever captured on film, Del Toro tags an almost indecipherable “What the fuck?” at the end of his line to great comic effect. It’s a cursing that is entirely native to his serpentine, too-cool-for-procedure personality, and proof that you don’t need to hurl a swear word at someone’s head in order to celebrate it (see 0:51).

–

25th Hour (2002)

Monty: Fuck the corrupt cops with their anus violating plungers and their 41 shots, standing behind a blue wall of silence. You betray our trust! Fuck the priests who put their hands down some innocent child’s pants. Fuck the church that protects them, delivering us into evil. And while you’re at it, fuck JC! He got off easy! A day on the cross, a weekend in hell, and all the hallelujahs of the legioned angels for eternity! Try seven years in fuckin’ Otisville, Jay!

Spike Lee’s post-9/11 crime drama has gathered popularity with age, and with good reason. It’s one of Edward Norton’s finest hours, and like Inside Man, proof that Lee can find a vehicle for his politics without preaching. However, the most Lee moment in this largely non-Lee film comes when Norton’s Monty confronts the mirror and rattles out the F-word at anything and everything — you, me, him, every race, every creed — and it’s a monologue that serves as cathartic moment for anyone that’s mad as hell and isn’t going to take it anymore.

–

Deadwood (2004-2006)

[Uh, just watch the whole clip.]

If Deadwood is, as it’s often labelled, ‘Shakespeare in the mud’, then a primary ingredient of that mud would have to be profanity. Tempestuous creator David Milch found new uses for the swear word, slipping it into the oddest part of a sentence and creating a new syntax in the process. Attempting to find Milch’s most effective use of ‘cocksucker’ is like trying to pick the best of Tony Soprano’s heavy-breaths, so I’m just going to close my eyes and place my finger somewhere along the series’ 36-hour timeline, and hope for the best.

–

Speed (1994)

Traven: We got a wad, pretty big.

Stephens (into phone): There’s a pretty big wad.

Traven: Brass fittings.

Stephens: Brass fittings. What else?

Traven: Hold on.

Stephens: Hold on.

Travers: (Beat. Surveys bomb.) Fuck me!

Stephens: Oh darn.

Sometimes it’s less the writer’s use of profanity that makes a mark, and more the actor’s delivery. Sometimes it’s less about the dramatic potency of the curse word and more about its unintentional hilarity. And if there’s anyone that knows unintentional hilarity, it’s Keanu Reeves, an actor that’s never quite been able to shake the Ted Theodore Logan (or perhaps, Keanu) from subsequent performances. It’s a tendency that can ruin an otherwise great film (Dracula), but in Speed, Keanu’s reactions to genuinely tense revelations give Peter Sellers a run for his funny money. This particular moment sees our slack-jawed hero discover a bomb underneath a public bus, and he responds with two words that perfectly capture the severity of the moment: “Fuck me.” Sounds a little lame, right? As I said, it’s all in the delivery. (Click here or on the image below to see the clip).

–

Terminator 2: Judgement Day (1991)

John Connor: No, no, no, no. You gotta listen to the way people talk. You don’t say “affirmative” or some shit like that; you say “No problemo.” And if someone comes on to you with an attitude, you say “eat me.” And if you want to shine them on, it’s “Hasta la vista, baby.”

The Terminator: Hasta la vista, baby.

John Connor: Yeah but later, dickwad. And if someone gets upset, you say “Chill out!” Or you can do combinations.

The Terminator: Chill out, dickwad.

John Connor: Great! See, you’re getting it!

The Terminator: No problemo.

It’s generally accepted that ‘fuck’ is the Rolls Royce of swear words, but sometimes a less brutal succession of letters is just as effective. The action classic Terminator 2: Judgement Day is basically a Rolls Royce showcase, but it’s an exchange between Edward Furlong and Arnie that stands out. In this scene, Furlong’s John Connor is attempting to teach Arnie’s Terminator how to talk like a human (or more accurately, like a 10-year-old that listens to Guns N’ Roses), and hearing the towering Austrian try his hand at a word that hasn’t been uttered by anyone since this film’s release is a necessary moment of levity. (Unfortunately I couldn’t find a version of the scene that wasn’t chopped up into nonsense, so refer to the quote while you watch).

–

Degrassi High (1987-1991)

Caitlin: Tessa Campanelli? You were fucking Tessa Campanelli?

Children of the early-’90s wouldn’t know much about recreational drug use or STDs if it weren’t for Canada’s half-hour high-school serial, Degrassi High. We watched the shocking exploits of Joey Jeremiah and Snake and Wheels as they battled the onset of pubic hair, and we liked it because it was risque without being explicit. But when the writers decided they’d end the series with the movie-length episode ‘School’s Out’, that safety net was yanked from under our feet and we were forced to watch the consequences of the characters’ shenanigans play out. Break-ups, ended friendships, a drunk driving accident that left an audience favourite blind, and a final comeuppance for Joey, whose infidelity is discovered by his long-time belle, Caitlin.

But perhaps the most effective moment in a show that managed to last five years without a single swear word was when both Snake and Caitlin proved they meant (adult) business by hurling the word ‘fuck’ at our Machiavellian protagonist’s Fedora-topped head. It may have been bleeped at the time, but the spine-shivers caused by hearing our ‘innocent’ Degrassians utter a word that had never been part of the show’s world still lingers today (see 0:43 and 1:15).

–

Jeremy Cassar is a screenwriter from Sydney.