Junk Explained: What Exactly Is Happening In Myanmar?

Everything you need to know about the unfolding crisis you've been hearing all about.

Myanmar has made a lot of headlines this week.

Yesterday, the country’s de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi broke her long silence on a violent conflict and refugee crisis that has been described by the UN as a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing”. She’s faced widespread international criticism for that response, which many see as far too weak.

Also yesterday, and slightly closer to home, The Guardian broke the news that the Australian government is offering to pay Rohingya refugees to return home, despite the fact that they’re the target of the violence.

If you’ve been seeing the news but have no idea what’s going on, it’s time to get up to speed. We spoke to Dr. Jean Jonathan Bogais from the University of Sydney to give you a backgrounder on what’s happening in Myanmar, and what Australia has to do with it.

What’s Happening In Myanmar?

The Rohingya people are an ethnic minority group in Myanmar (formerly known as Burma). Before the current crisis escalated in 2016, there were estimated to be around 1 million Rohingya people in the country, which has a total population of 51 million. We’ll get to the current crisis in a sec.

The Rohingya are technically stateless, because Myanmar refuses to recognise them as citizens and denies them a bunch of rights as a result. They face intense violence and discrimination within the country, and have been described as the most persecuted minority in the world.

This persecution has been going on for decades, but it’s seriously escalated in the past two years after a group of Rohingya militarised to oppose the violence they were experiencing. This only intensified the violent conflict, leading to a top U.N. Human Rights official describing the violence as a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing” just last week.

There’s been a massive outflow of Rohingya refugees fleeing Myanmar.

Myanmar’s military, along with a number of other groups, have staged a violent campaign against the Rohingya people, burning down hundreds of villages and killing survivors.

As a result of this intensified violence, there has been a massive outflow of Rohingya refugees fleeing Myanmar for neighbouring Bangladesh. In recent months, around 400,000 Rohingya are estimated to have fled — a truly staggering number, and one Bangladesh is not equipped to support.

Why Is There So Much Hatred Towards The Rohingya?

Dr. Bogais has been studying the conflict in Myanmar for years. To understand it, he says we need to consider the country’s history.

It’s important to remember that like much of Southeast Asia, Myanmar was once colonised by the British. As inevitably happens when a foreign power with next to no understanding of local culture and customs tries to impose its rule on a place, this involved some pretty arbitrary drawing of boundaries. The way the British divided up territory often ended up grouping together ethnic groups who would not consider themselves part of the same nation, as well as drawing borders through groupings of people, leaving fragments of communities scattered across a bunch of different countries.

This is what happened in Myanmar: a bunch of different ethnic groups have been thrown together, and none of them have ever really recognised the government. To make matters worse, the Buddhist majority and the Rohingya minority ended up on different sides during World War II.

As Dr. Bogais puts it, that history of conflict meant “we had the dynamics of war between the Burmese forces and the Rohingya already. That conflict is continuing, and what we have today is only a progression from the 1940s. It’s just been slightly better and slightly worse over time, up and down, and right now we’re getting to the high part.”

There are, of course, further layers of complexity to this. There are also other internal conflicts in Myanmar that don’t get talked about as much as the Rohingya issue, despite being extremely serious in their own right. But in short, the thing you need to understand is that the conflict with the Rohingya is not a recent thing — it’s been a part of the history of Myanmar for decades. That’s part of the reason people are not optimistic about a fix any time soon.

What Did Aung San Suu Kyi Do That’s Making People So Angry?

The name Aung San Suu Kyi is probably familiar to you, either because of recent news, or because she won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991. She’s best known as one of the world’s most famous political prisoners, remaining under house arrest for almost 15 years after the military refused to acknowledge the election of her political party. She was finally released in 2010.

She’s now the de facto leader of Myanmar, though the country doesn’t really have a proper government up and running, and has been under military rule for a long time.

Suu Kyi has attracted a lot of criticism lately for remaining silent on the massive violence happening in her country, and the ensuing refugee crisis. There’s been lots of pressure from the international community for her to break her silence on the issue, and yesterday she did, with a cautious speech that avoided publicly condemning anyone or taking firm action. She’s copped more criticism from the international community as a result.

It seems at face value to be a pretty straightforward case: people are dying, and a leader appears to be doing nothing about it. But Dr. Bogais says the situation is much more complex than that.

“I don’t believe she has said enough about what to do with the Rohingya,” he told us, but emphasised that we have to also be realistic about what she is able to do.

In live speech to nation, Aung San Suu Kyi says Myanmar "does not fear international scrutiny" over #Rohingya crisis https://t.co/WURNdPnhmD pic.twitter.com/8QT9BJlFKw

— BBC News (World) (@BBCWorld) September 19, 2017

There are a number of problems here. One is that Aung San Suu Kyi was elected only 18 months ago, in a country that still lacks much of the governmental infrastructure necessary to get things done. Another is that after so many years of military rule, what Bogais refers to as a “parallel economy” has formed, where “no matter what you want to do in Myanmar today, you have to deal with the military.” As a result, he says “you cannot remove the military” in the way that so many international observers are calling for.

In short, he says, “Aung San Suu Kyi was set up to fail. The expectation that she could stop the military and resolve the conflict was a delusion, and unrealistic, and put her in a position where she had no choice but to try to compromise.”

“The best way to do that yesterday was to avoid making any statement that could inflame anything, which is what she did. I’m not defending her, but we have to be analytic.”

One thing Bogais will criticise Aung San Suu Kyi on, though, is statements she’s made about Rohingya people being able to return to Myanmar.

“She said they could come back,” he said, “but they would have to go through a verification process that looks at citizenship, that will make it difficult for them. And if they were to come back, there is no peace. Most of their property has been destroyed — it begs the question, coming back where, to what, and to whom?”

If Things Are So Bad, Why Is Australia Trying To Pay People To Go Back There?

The situation with Australia and Manus Island is connected to a separate human rights issue: Australia’s treatment of asylum seekers.

As you know, Australia has been sending asylum seekers who arrive by boat to offshore detention centres on Manus Island and Nauru. Last year, Papua New Guinea ruled that the detention centre on Manus Island was illegal, breached human rights, and must be shut down.

The deadline for the centre to close is in October, and Australia has been doing a bunch of objectively awful shit to try to clear the camps — stuff like cutting off power and water while people are still living there. Now, they’ve been offering to pay Rohingya refugees on Manus if they return to Myanmar.

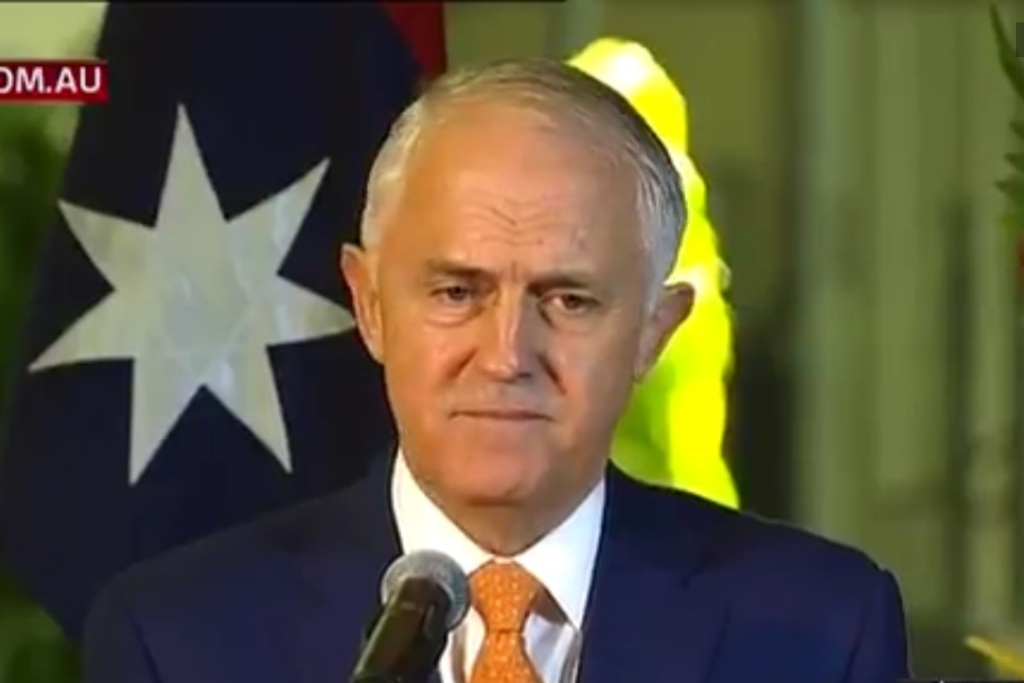

What morally bankrupt leadership looks like. Turnbull trying to pressure #Rohingya he is locking up to return home. https://t.co/coPxuLtyxM

— Kon Karapanagiotidis (@Kon__K) September 19, 2017

This is, quite obviously, highly unethical. You shouldn’t need an expert to tell you this, but in case someone from the Australian government is reading, here’s Dr. Bogais in the issue:

“Paying the Rohingya to go back to a zone of conflict is like paying asylum seekers to go back to Afghanistan,” he says. “This is highly unethical — it’s a way to pass the buck, to say it’s not our problem.”

“When you have a turn back the boats policy, you’re saying you don’t want people to die on your shores, but it’s fine for them to die somewhere else. Especially when at the same time you’re criticising the Myanmar government for not doing enough, there’s an ethical issue.”

This is the only part of this story that Dr. Bogais would say is straightforward: we need to do better.

“It’s not a complex issue. I think Australia, like other countries, could do much better, and should do much better on refugees.”

“Any of the Western democracies who are telling people what to do today should actually come to help by taking some of these refugees,” he says. “I grant that Australia cannot take 400,000 Rohingya, but any numbers will be important, because it will show a will to contribute.”

–

Feature image via Wikimedia Commons and Voice of America.

–

Sam Langford is a Junkee Staff Writer. She tweets @_slangers.