Michael Kiwanuka On Love, Hate, And Everything In-Between

"When I’m singing 'I’m a black man in a white world', that’s not out of bitterness or out of anger. It all comes back to knowing your identity, and taking comfort in it."

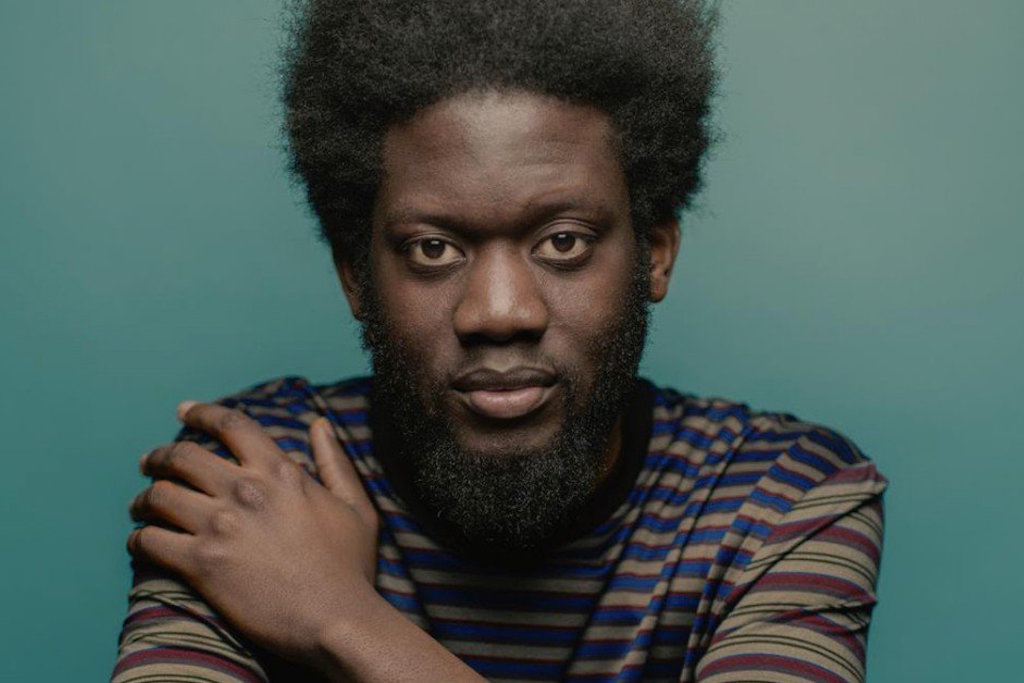

In a relatively-quiet corner of Three Williams, a bustling cafe in the heart of Sydney’s Redfern, Michael Kiwanuka sits contently and ponderously. He’s fresh from Splendour in the Grass, the Byron-bound true survivor of the music festival recession, where he and his band held their own on a line-up built on the foundation of heavyweights like The Cure, The Avalanches, The Strokes and a couple of non-”The” bands for good measure.

Indeed, more eyes are on Kiwanuka now more than ever – his second album, Love & Hate, has been praised as a masterwork within the realm of contemporary soul music; and they’re not unsubstantiated claims. With glorious orchestration and stunning delivery, it’s an album that resonates long after its final strains ring out – an important, aware and engaging look at the world as seen through Kiwanuka’s eyes.

FasterLouder: For those that aren’t aware, Love & Hate is an album that’s been in the works for quite some time. Take us back to where the album’s initial formation started.

Michael Kiwanuka: In about 2014, about the start of that year, I started doing some demoing and some studio sessions and toying around with some of the song ideas that I had been writing toward what I was hoping would be the next album. It’s funny… so much of what I was working on at that time ended up being fairly different to what would end up on this album. A lot of those songs started really simply – me at the piano, me playing guitar – and they made it through to the final stages, but they evolved a lot in that time. I found the sound I was going for as the writing was coming along. It took me awhile, actually, but I think that once I found the right people I was able to properly pursue the right creative direction.

How did the songs expand from those humble beginnings of just guitar or just piano? Did you have ideas for arrangements in your head as you were writing these songs?

It was a product of working in the studio a lot of the time. I’ find myself with a riff, and then just immediately take it as many directions as I wanted. When I’m at home, I’ve got my guitar, my laptop and GarageBand; and that’s about it. When you’re in the studio, you can overlay drums, percussion, more guitar, bass… all as you’re writing. You can dream bigger and go with it, all the while writing lyrics. I’ve never really had that process until doing this album, and it completely opened up my world as a songwriter.

There’s a lot of key contributors to Love & Hate, but it would be amiss to go past Brian Burton – aka Danger Mouse – as a central force on the album. Brian is the kind of producer that is instantly recognisable for having a sound. He can take Norah Jones and make her sound like Danger Mouse. He can take Cee-Lo Green and do the same. He even just did it with the Chili Peppers. Was it at all a concern that he would be encroaching on your territory at all?

[laughs] Yeah, a little. I knew that there was a downside to working with a producer that’s so famous. It can kind of engulf the music, in a way – it can eclipse it. Being a quite young artist, at least in terms of albums, I knew from the outset that it could be a hindrance. I wanted to make sure that my own personality was kept in there. It was something I was aware of, but it worked out alright. It ended up being more of an exchange, more than anything – there were definitely elements and ideas utilised on his records that I wanted to try out, and there were elements of my singing and songwriting that he wanted to bring out more of, as well. We just had to find that balance.

How did the other players on the album come about? Was that more of Brian’s initiative or more yours?

The thing is that I was trying to make a record for a long time. I had stuff all over the place – different ideas, different songs, different producers. In order to make the record come together, I had to pull back in a lot of different pieces of the puzzle from a lot of different places. That meant working alongside the people that had been a part of the project along the way. Before Brian was in the picture, I was working with this guy Inflo [AKA Dean Josiah], and he produced a bunch of stuff and co-wrote some things with me. I felt that, in order for this record to be the best reflection of me possible, I knew that I couldn’t just abandon all of the work that I’d already done. I couldn’t just scrap it and then do it all again with Brian. I knew that I wanted my other work to be represented in there, as well. As great as being a solo artist can be, it’s also nice to have people around. It’s good to have collaborators that push you out of your comfort zone.

We’ve looked at the album from a musical standpoint, but let’s change tact and discuss your personal lyrical input to this record. There appears to be a sense of disconnect in a lot of these songs when it comes to their subject matter – it’s a considerable distance between who you “are” and who you’re “supposed” to be. It’s conflict between the id and the superego, in a way, but there’s also more to it than meets the eye. What was going on in your life to lead to such a degree of introspect?

A lot of things were on my mind. One of the things about trying to be a musician is your identity. It comes up a lot… I mean, you’re putting music out under your own name. That’s you. That might seem simplistic and obvious, but I got to thinking a lot of the person I was and who I wanted to be outside of making music. Weirdly enough, it was the only way I could find a reason to go to the studio and make music. Pleasing an A&R man, commercial success… that alone is not worth working that hard to make something that was good. It’s not enough. It had to be something else. That’s where I found myself singing about what was going on in my head: Who I was, how I wanted to be perceived, how people perceive me, stereotypes I’ve experienced. I’ve always been interested in where people fit in, and where they find themselves in the world. This lead me to think about where I see myself, where I fit in. I used that as inspiration, and it kind of sprung me into making songs.

‘Black Man In A White World’ has been a major talking point of the album, and for very good reason. It feels incredibly pertinent – not just for the high levels of tension for people of colour in America, but it’s also impacting on Britain right now as well…

Yeah, absolutely. It’s very interesting that the song was written before all of that stuff was making news, and then as it came out it started to kind of unravel. I think that aspect of one’s identity has always played a bigger part of who you are than we’ve ever been willing to admit – and now, with everything that’s going on, it’s become a lot clearer. With something like Brexit happening… that’s people worried about losing that part of their identity, losing who they are. They’re going as far as to vote to leave Europe in order to keep that. There’s a history in England of people losing jobs and industries going – much like America, much like places like Detroit. That’s an identity – where you work, where you live, your family’s business. We take that for granted, but that’s what builds us and what gives us part of our identity. It’s part of what makes us who we are. When that’s encroached upon, people get angry. They get bitter. They act extremely – whether that’s a vote to leave the EU, locking someone up or shooting someone.

Has it affected you to consider at all that people with a completely different background to yours – indeed, such as a white person here in Australia – will be learning about POC experiences outside of America through your music?

It has, yeah. That’s especially been the case with ‘Black Man In A White World’. When I was writing that song, it was definitely done with a degree of trepidation – I kept thinking to myself, “What are people going to think of this? What are people going to say?” I barely even see black people at my own shows – I don’t know what it’s like anywhere else with soul music, but in England my music isn’t really listened to by young black kids. There’s a history to this kind of music, but it doesn’t really interest them. I knew that what I was writing would be quite strong in terms of resonating with my typical audience. I don’t know… I guess there was a period of time where I was definitely worried. After awhile, though, I started to think about who my favourite artists are and what they would do in my situation. I came to realise that they put themselves out there. They’re vulnerable, and I think that’s important. Look at a record like [Bob Dylan’s] Blood on the Tracks… I feel that emotionally. Even before I knew what he was singing about, I could feel what he was singing about. That’s the beauty of art for me.

There’s a line in the song… “I’ve lost everything I had/I’m not angry and I’m not mad.” That can be interpreted as a numbness to oppression through means of systemic and institutionalised racism, which can often feel so much worse than anger because it means you’re feeling nothing. Is a reading like that close to the mark at all?

With that lyric, I was thinking about myself growing up. Placing myself within society in a greater sense, I found myself wanting to relate to and connect to something and just not being able to find it. I think that lyric, specifically, is about my relationship to music more than anything. When you lose that sense of identity, you can lose confidence in yourself. Before that song, I had a period where I stopped enjoying making music and writing songs. I was saying that I’d lost this sense of being, this sense of belonging. As far as singing “I’m not angry and I’m not mad” is concerned… that was to do with taking pride in myself. I wanted to make clear that when I’m singing “I’m a black man in a white world”, that’s not out of bitterness or out of anger. I was thinking more specifically about being ostracised, or being told what kind of music to make. It all comes back to knowing your identity, and taking comfort in it.

You’re dealing with a lot of bigger-picture issues here – and one would suppose that’s to be expected from an album with as wide-swinging as Love & Hate. The most interesting thing about the album, from that perspective, is the marriage and intertwining of the personal and political. These are huge topics, but you’re approaching them from a very direct individual perspective.

I didn’t want to hide behind any lyrics this time. I wanted to find reasons as to why people would want to listen to me. I remember Inflo asking me that when we were working together – there’s a lot of good singers, there’s a lot of good bands, there’s a lot of good guitar players. What makes an artist stand out is what they’re saying – and, by extension, the songs in which they’re saying it. When I realised that, I went deep and took that direction. I wanted to make an album that would stand out, because I’m interested in making music that people connect with. It could be a stylistic thing or a catchiness thing, and those were things I could do; but I found that if I wanted to make an album that would really be remembered at a time when there’s a saturation of music, then what I was saying had to be as strong and as important as the music itself.

Let’s wrap up with a question not about you: Are there any artists in British music right now that you think deserve attention and recognition?

There’s a singer called Rukhsana Merrise. She’s on Communion, this label that I used to be on, and she works with a lot of producers and songwriters that I grew up with. She’s making a mix of folk, soul and pop. It’s different – it’s not vintage soul, it’s her own thing. I’d definitely tell people to check her out.

–

Love & Hate is out now through Universal Music.

–

via FasterLouder.