The M.I.A. Documentary Is A Reminder That The 2000s Weren’t Ready For Her Revolution

In 2010, one truffle-coated French fry turned M.I.A. from a political provocateur into a poser.

In 2010, one truffle-coated French fry turned M.I.A. from a pop music political provocateur into a poser.

In a now-infamous profile by The New York Times, writer Lynn Hirschberg paints M.I.A. as “politically naive”, a pop-star who raps about refugee crises as a chic point-of-difference. During lunch, M.I.A. tells Hirschberg she doesn’t care if people label her a terrorist sympathiser, munching on truffle-coated chips between words.

As think-pieces were spurned from a single image, the chips became The Perfect Metaphor For Everything Wrong With M.I.A.. Never mind that it wasn’t strictly accurate — when M.I.A. later posted secretly-recorded audio of the interview, we hear Hirschberg order the fries.

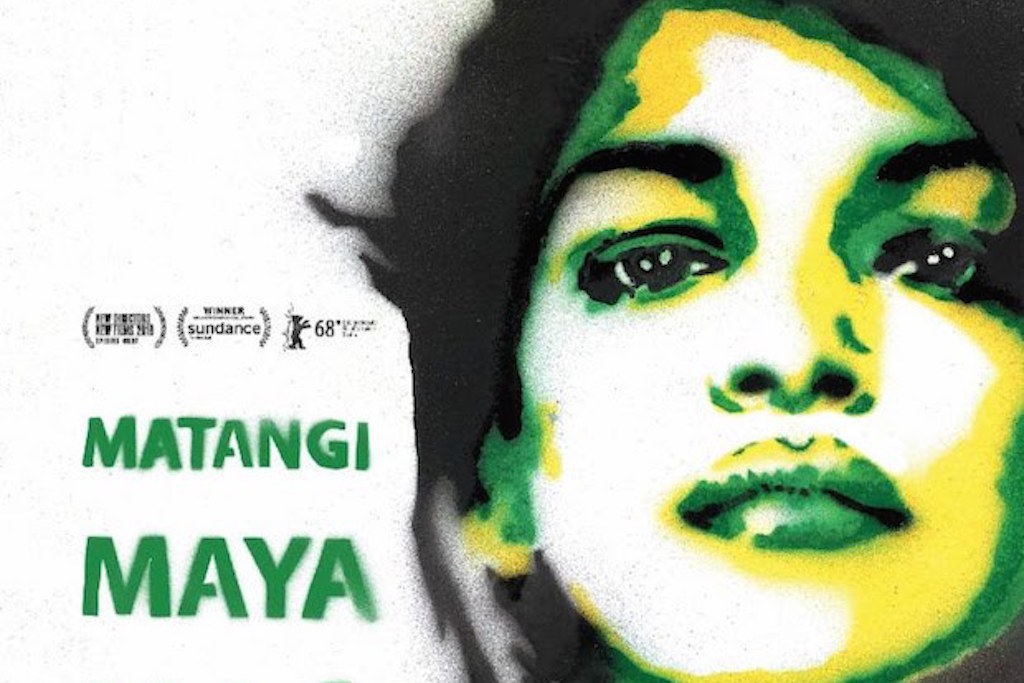

‘Truffle-gate’ is only a blip in MATANGI / MAYA / M.I.A., Steve Loveridge’s long-awaited documentary on Maya Arulpragasam. But it’s one of many moments that layer to reveal Arulpragasam reached a level of fame that necessitated she shed an identity — that she had to be successful or the political rapper, not both.

She refused — and so became a vapid terrorist sympathiser to sources as disparate as Fox News, Oprah, and her ex-lover Diplo.

“Started At The Bottom, But Drake Gets All The Credit”

Rather than follow the rapper on a new project — M.I.A. says 2016’s AIM was her last album — the documentary spans decades in a (mostly) linear fashion. Loveridge draws upon more than 700 hours of footage that Arulpragasam, once an aspiring filmmaker, shot herself as a teen and twenty-something in the late ’90s and early ’00s.

Born in Sri Lanka, Arulpragasam grew up in London, where her family sought asylum from a civil war — one stoked by her father Arular Pragasam, a self-professed founder of the Tamil Tiger independence movement, widely recognised as a terrorist movement.

This revolutionary spirit flows through M.I.A’s discography, a diasporic sampling of refugee and immigrant cultures across five albums, tied together by frustration.

“Arulpragasm has always been creatively driven by a need to process the complexities of her immigrant identity.”

Loveridge’s documentary avails the idea that M.I.A. is a manufactured star. By centring Arulpragasam’s own vlog-like footage, we see how she’s always been creatively driven by a need to process the complexities of her immigrant identity.

We see Arulpragasam float through her early 20s following an interest in film. At first, she turns her camera on herself and London’s immigrant community before, through a chance encounter, becoming the right hand woman of Justine Frischmann of ’90s Britpop band Elastica. Here, she begins to work on music, but while filming tours, Arulpragasam feels unfulfilled — in 2001, she visits Sri Lanka to connect to her history.

There, she learns a hard truth: that her childhood makes her a foreigner in both Britain and Sri Lanka.

“There’s always going to be something different about us that doesn’t relate to a white experience or a black experience,” we hear her later say to fellow London rapper Afrikan Boy. “It’s always something extra. Something else that you have to go and do, which is connect with your back-homeness.”

It’s this placelessness that pushes Arulpragasam. Throughout MATANGI / MAYA / M.I.A., there is a sense that there is nothing holding her back.

Back in London, we see an unknown Arulpragasam literally knock on the door of XL Recordings armed with tapes, dressed in her own designs, and ready with an impromptu performance of ‘Galang’, her first hit. For a while, it’s height to height, as M.I.A. catapults to stardom.

Rather than mere fan service, these scenes centre Arulpragrasam’s unwavering self-conviction and complex connection to Sri Lanka, two oft-overlooked pillars of her career. As she rapped on the title track of 2013 album Matangi, she “started from the bottom, but Drake gets all the credit”.

Then As M.I.A.’s Career Took Off, So Did Violence In Sri Lanka

In the first months of 2009, M.I.A. was everywhere thanks to ‘Paper Planes’. The song, a Diplo-produced satire on immigrant stereotypes with an infectious sample-filled chorus (‘All I want to do is [three gunshots] and take your money [cash register opening]’), was nominated for both a Grammy and Oscar, having featured in Slumdog Millionaire.

For the first five months of the year, violence erupted in Sri Lanka, ultimately ending the country’s civil war. As the Tamil Tigers made last stands against the Sri Lankan government, the brutality was equivalent to a genocide, the death toll for the period reaching (disputed) estimates of 40,000.

Arulpragasam used her platform to ill effect — in Loveridge’s documentary, we watch her be cut off by Bill Maher, told to stay in her lane by talk-show panelists, and parodied to high hell.

On the Grammys red carpet, Arulpragasam argues with a CNN reporter for the station editing out her comments on genocide in a previous interview. The reporter laughs it off. “You’re the first person that we’ve interviewed that says, ‘The piece was too much about me,’” the reporter says. “People mostly want it about them.”

Watching M.I.A. / MATANGI / MAYA, it’s clear that Arulpragasam is naive for expecting anything else on the red carpet. As the world’s most famous Tamil, she had a platform which demanded a sanitised message — one without the ‘g’ word.

“I tried to do it the way they wanted me to do it, which is learn a script, learn the five sentences you wanted to repeat in the news,” she says.

It doesn’t work, which is no doubt why she later learns to distrust the media. Beyond recording the NYT interview, suspicion sweeps through her 2010 album MAYA, where songs like ‘The Message’ describe how governments spies on its citizens through technology, a prescient image laughed off at the time as paranoid.

Even still, Arulpragasam remains guarded. After watching the documentary for the first time at its Sundance premiere, she told Billboard she feared what Loveridge, a friend who she met in film school more than two decades ago, might do with her footage.

Born Free

Nowhere is it Arulpragasam’s refusal to concede more apparent than her $6.6 million dollar standoff with the NFL after flipping the bird to the world during Madonna’s 2012 Superbowl show during her 15-second verse in Madonna’s ‘Give Me All Your Lovin”.

In the doco, we see the immediate aftermath. When Arulpragasam literally runs away from NFL officials, it’s clear she hasn’t taken stock of the gravity of the situation.

“There’s a sense Arulpragasam occasionally pokes a beast to poke it, conflating agitation with activism.”

Later on, she expresses disappointment at watching Madonna being bossed around backstage and “bending over” for the NFL before the show. It’s just one of many dissolutions, yet Arulpragasam refuses to follow lead and pays the price, settling for an undisclosed amount.

Still, there’s a sense Arulpragasam occasionally pokes a beast to poke it, conflating agitation with activism. While she says it was a mere coincidence that her video for ‘Bad Girls’ came out the same day as Madonna’s saccharine ‘Give Me All Your Lovin”, these things don’t just happen. What’s badder than upstaging the queen of pop at a gig that doubles as a coronation?

It’s clear that M.I.A. has a reputation to uphold. She might rap on Madonna’s track that she doesn’t give a shit, but MATANGI / MAYA / M.I.A. is proof, if anything, she cares too much. It’s her biggest asset and her biggest flaw.

—

MATANGI / MAYA / M.I.A. screened at Sydney Film Festival. It does not currently have an Australian release date.

—

Jared Richards is a Staff Writer for Junkee, and co-host of Sleepless In Sydney on FBi Radio. He tweets at @jrdjms.