Meet The Tasmanian Comic Book Artist Taking The United States By Storm From His Bedroom

Matt Groening, Bob Odenkirk and David Cross are all fans. Here's why you should get to know Simon Hanselmann.

In a nondescript building on the outskirts of Washington DC a man stands nervously on a low stage, illuminated by intermittent camera flashes and dull fluorescent lights. A lustrous russet wig, a billowing cream wedding dress and rows of fake pearl bracelets offset his strong jaw and broad shoulders. He reaches into his stuffed brassiere, pulls out a piece of paper and unfolds it before fixing his gaze on a small pile of graphic novels sitting on a stool.

“I, Simon Hanselmann,” he intones deeply. “Take you, comics, to be my lawfully wedded art form.” The audience, iPhones aloft, laugh gently. He flicks his head, blinks his fake lashes and continues. “It’s been 26 years of unbridled bliss…through obscurity and low-level Internet infamy – a whirlwind romance for the ages,” he pauses to allow another ripple of laughter to pass across the crowd.

“I will be with you – through sickness, profound sadness, delirious highs, crippling insecurity, epic personal fuck-ups, and the inevitable critical backlash, ‘til death do us part. Which may realistically be in about five years.”

Fuelled by further warm laughter and the goodwill of smiling faces, he pushes his synthetic hair back and theatrically announces: “I fucking love you, you cheap bastard. You continually screw me over and undervalue me, but I just can’t stop wanting you.”

“I am a modern woman. Smiley face X O X O hashtag forever.”

He walks across the stage, flinging the paper into the front row.

“Nailed it.”

–

One month before ‘marrying comics’ – a publicity stunt dreamed up by him and his publisher, acclaimed Tasmanian comic book artist Simon Hanselmann is sitting in his cramped apartment, dressed in jeans and a crumpled t-shirt.

“Sometimes I dress for interviews,” he says ruefully. “Sorry.”

That he has found the time to talk at all is impressive, and throughout our conversation he rarely stops working. His work appears in The New York Times, Pitchfork Review and The Believer; today he’s colouring his weekly strip for youth media website Vice. Simpsons creator Matt Groening, renowned comedians Bob Odenkirk and David Cross, and Ghost World author Daniel Clowes are all confirmed fans. Others follow him on Tumblr where he is, in his own words, a “low-level celebrity and drag personality”. Within a month, his compilation Megahex will debut in the Top 10 of the New York Times Best Seller list.

Tracking how his trajectory of success began requires looking back. Looking back isn’t always easy.

“I just went to the bank this morning, put $400 in my mum’s account to cover her Suboxone for the next month,” he says sighing, referring to her latest drug-withdrawal medication. “I’m hoping she’s not going to go straight out and spend it on drugs. People tell me to cut her off, but I can’t do it. I’m all she’s got,” he smiles wanly. “It’s just this searing empathy I have with her situation.”

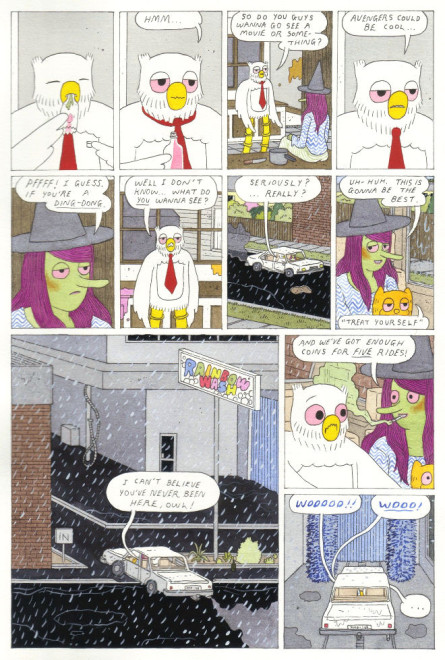

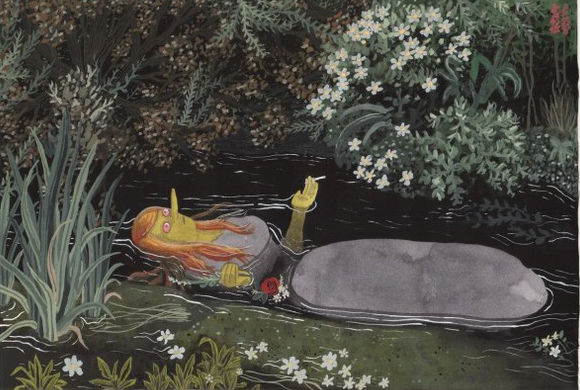

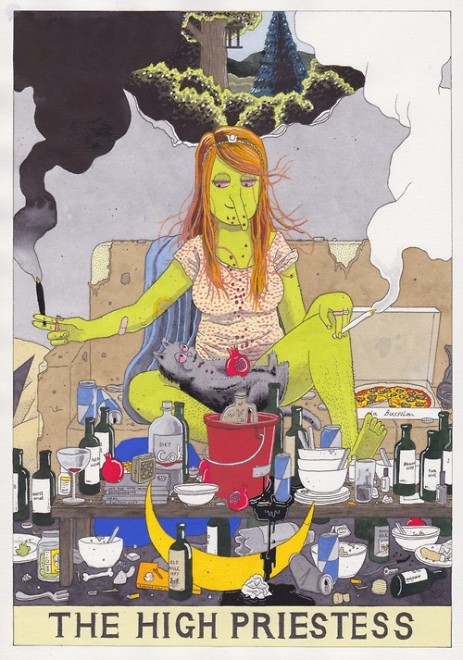

Begun in 2010 and showing no sign of ending, Megahex is a semi-autobiographical soap opera about four characters. It too builds on his “searing empathy”. Megg is a depressed, frequently stoned witch, Mogg her boundary-invasive cat, their housemate Owl (a misanthropic anthropomorphised owl) and Werewolf Jones, a pathetic, lecherous hanger-on. The trigger warning adorning the cover – strong coarse language, depression, rimming, drug use, and mental and physical abuse – is not just for promotional reasons.

“I bang on about addiction and drug problems and horrible Hobart scene politics,” he says keenly before we’re interrupted by the buzz of a mobile phone and a glimpse of another overarching influence.

“Here’s a text from my mum,” he informs me, putting down his brush and grabbing his phone. “She’s probably telling me she’s been written off by everybody. ‘Booked into St Johns on the 30th,’” he reads.

A 2012 report from the Australian Bureau of Statistics found half of all Tasmanians are functionally illiterate and innumerate. One-third of the state relies exclusively on welfare payments for their income. In particularly disadvantaged regions of the state, where the unemployment rate is over 50 percent, it’s easier to score pot than find someone who can read a prescription. This is the world in which Megahex was born.

“I think my situation was quite common in Tasmania,” he says, crouching over his low table, dipping his brush carefully in a little jar of ink. “Rampant unemployment and people turning to drugs. My mum did a really good job. I always had slick lunches at school. Nice sandwiches and Roll-Ups and muesli bars. She did provide a really good home.”

Growing up an avid reader and writer, Hanselmann started with Helen Nicoll and Jan Pienkowski’s popular books Meg and Mog, a series that inspired his own work. He quickly progressed to comics like Tintin, Asterix and Mad, which he copied and expanded on. His love of writing and drawing was a passion fed by his mother who he later realised was stealing books for him. “She kept me literate and clean and nice,” he says. “But at the same time she had a monster drug habit.”

When his mother was passed out for days at a time, he was often cared for by a confused and anxious grandmother, unsure what was happening to her daughter. Hanselmann acknowledges these lapses in care often had harrowing consequences.

Like his mother, Hanselmann uses drugs to cope with anxiety and to maintain a work ethic he describes as “escapist”. His earliest published works are profane, drug-fuelled comic strips that satirised his friends. Despite being full of local references and dick jokes, his drawing skills impressed enough Tumblr readers to draw a small following. Fearlessly mining his life for inspiration he developed Megahex and, as he puts it, “boom, everything suddenly blew up”.

–

Like many Melburnians, he had already been published at Melbourne’s legendary zine store/DIY publisher Sticky Institute. Fellow comic artist David Mahler watched Hanselmann develop his style and saw this sudden spike in audience.

“Starting out, I think that’s what Megg and Mogg was for him,” he says. “He put his own face on these characters once he’d already lured people in with his other work and made them fall in love.”

Like many of his friends, Mahler learned more about Hanselmann’s relationships with his mother through reading his comics than conversation. More notably, he also learned about his friend’s cross-dressing and gender questioning.

“People say that I write female characters well,” Hanselmann explains. “But I’m really just writing myself. I identify as a flesh-swaddled skeleton. I really don’t see huge divides between genders, I never have.”

Hanselmann puts down the brush and reaching for his tobacco pouch. “I’ve been cross-dressing since I was pre-sexual and the weird thing is reconciling with how it’s gotten mixed in with sexual stuff. It’s erotic wearing women’s clothes…” he trails off. “Which feels creepy. It makes you feel like a creep.”

Growing up, Hanselmann became used to strangers visiting his house to buy drugs from his mother. When he was 17 a police raid on his home resulted in him getting strip-searched and his stash of women’s clothing uncovered. “I was super-embarrassed. They were like: ‘Aw, these are trophies are they mate?’”

“‘Yeah. Trophies,’” he deadpans in disgust.

Rather than being something done in secret, Hanselmann’s American and European publishers now expected him to cross-dress for his promotional tours.

“I’ve done it to myself by becoming a Tumblr drag personality,” he says resignedly, going to the window, opening it and exhaling a steady stream of smoke. “So now people expect it. I feel like I’m underperforming if I don’t dress up.”

–

Fellow artist David Mahler says artists who draw extensively from their own lives risk attracting an exclusively like-minded audience. In Hanselmann’s case, opening up about his gender confusion in an interview with The Comics Journal last year proved to be a boon, and he became an inadvertent pioneer.

“After that interview I had 300 emails in the days after. Well, two death threats and about 300 very positive emails, including five other cartoonists coming out to me about similar problems,’ he says.

“I feel better since coming out, but still it’s a whole new kettle of fish. Reconciling the whole thing and doing it in front of a big audience and having expectations.”

Coming out to his family as a cross-dresser wasn’t something Hanselmann planned to do. In what now seems a pattern, Hanselmann did something that came naturally, and someone else deemed it newsworthy. In this case, his hometown newspaper, the Launceston Examiner, devoted a double-page spread to his success, adorned with Facebook-sourced shots of him in drag.

Informing the interviewer that his cross-dressing wasn’t common knowledge amongst friends and family, he still sounds irritated.

“I told them, ‘this is me coming out to my entire family and friends down there. Can you please send me the interview before you print it?’ They didn’t.”

Conceding the article was ultimately helpful in telling his story, Hanselmann admits he is still incapable of separating his mother’s judgement from his own sense of self worth. His recitations of her offhand remarks still sting.

–

Hanselmann’s meticulously tidy yet incredibly cramped bedroom-cum-studio is full of evidence that he is in the throes of success. New copies of Megahex translated into Spanish, French and Italian lie in neat stacks. Piles of ‘roughs’ or storyboarded pages sit by a makeshift Ikea desk, each a surprise inclusion with every order he mails out.

“I guess they’ll turn up on eBay one day”.

His work desk, a small rectangle of chaos, is littered with grubby jars, coloured water, dainty brushes, a packet of cigarette papers and scattered tobacco. Books cover the walls, their spines colour coded and height-matched. The space above his desk is adorned with scraps of paper; ideas, sketches, scribbles and a schedule for his upcoming 20-state American tour.

Hanselmann puts his work ethic down to a consistent use of marijuana, a vice he occasionally battles with and one that infuses many of his stories.

“I quit for six months about a year ago. I always come back to it though,” he sighs. “When you’ve got to do 18 hours of work a day, it’s fucking boring! I like the repetition but it’s also horrible, and it helps,” he gestures with the joint in his hand. “I’m 33 at the end of the year, it’s got to catch up with me at some point. I don’t want to be a drug-fucked old hippy.”

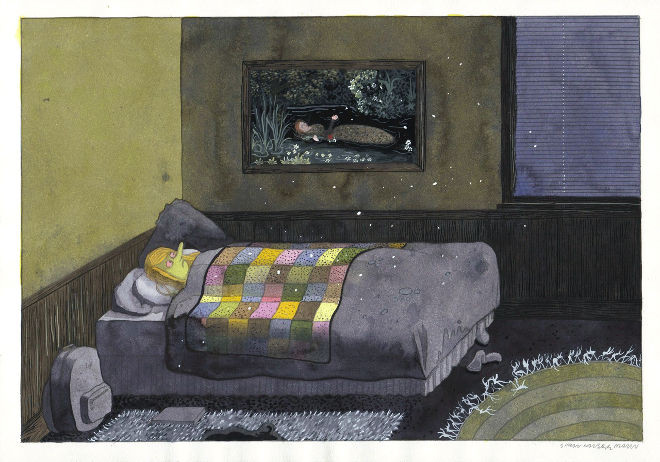

“A lot of comic readers and artists are lonely and pretty antisocial,” says David Mahler with a laugh. “The Internet has made it a lot better, but it’s still pretty horrible.” He cites the repetitive nature of the work as being the most difficult thing to deal with. “I’m sure it feeds the depression as well, so I think it’s cyclical. Simon is not going to suddenly start making these joyous works. He might make something joyous now that he’s gone overseas and getting acclaim, but he’s still going to come back home and lie on his ‘sadness mattress’ and watercolour Owl’s beak until 3AM.”

–

Hanselmann’s next project, Megg’s Coven, is a ‘straight verbatim’ account of visiting Launceston to put his mother into a rehabilitation clinic. “Broken families and years of addiction and brokenness,” he explains. “All her friends are involved in the drug scene and she just gets pulled in. She’s using more, so the story keeps writing itself. I’ve got 1,000 pages worth of material planned at the moment,’ he says, gesturing toward a pile of sketchbooks.

“It takes so long to draw, I’m just behind. I’ve got years of Megg and Mogg in me, really good stuff,” he says emphatically. “It’s going to get more dramatic, and then I’ll do something different eventually.”

While it’s hard to think of a time that Hanselmann wasn’t ‘different’, the pressures he faces now are new. Now, they come in the form of curious TV producers, optimistic foreign language publishers and emotional readers. “I just got to work on my health and try and get happier and more confident with my life.”

Happiness has since come in the form of a second wedding, this time to a human, American publicist Jacq Cohen, the woman who ‘discovered’ him on Tumblr and connected him to his publisher, Fantagraphics.

“We’re both really passionate about comics and intense hard work. We Skype everyday and are trying to sort out this damn visa thing and long-distance.”

Meeting several months later and asked whether he’d revise his life expectancy from the ‘five years’ mentioned in his first wedding vows Hanselmann says despite being “manically frazzled,” the combination of wider fame and his new marriage has changed his outlook.

“I’d been saying to her, I feel happier than I’ve ever been. She’s very accepting of ‘girl me’ and that part of me. Everyone knowing about it, I feel like a stigma has been lifted. I still struggle with guilt and shame and bullshit I have to push through, but…I’m just so fucking busy!”

–

Andy Hazel is a freelance journalist based in Melbourne who works at The Saturday Paper.