Learning About Australia Through The New Yorker Archives

What does the world's most famous magazine have to say about the far side of the world?

For three short months, until the end of September, The New Yorker has opened its archives for us, the freeloaders, to feast on the wealth of stories and profiles it has harvested since 2007.

There are many wonderful profiles that you will no doubt find your way to eventually, but first, how does Australia look through the eyes of the most famous magazine in the world? We are often mentioned for progressive healthcare and of late, successful gun control, but on a number of occasions the masters of long-form take a closer look at what happens down under. Here are seven of the best.

–

“The Miner’s Daughter” by William Finnegan

“The sheer distorting weight of Rinehart’s wealth is perhaps best understood in relative terms. The American economy is ten times the size of Australia’s, so in the United States an individual fortune equivalent to hers in relation to the national economy would be somewhere around two hundred billion dollars. That is roughly the combined net worth of the four richest Americans. Or seven Michael Bloombergs.”

The New Yorker loves its plutocrats, so it was really only a matter of time before it found its way to Gina Rinehart. William Finnegan takes us into the famously private life of the world’s richest woman, presenting a more intimate profile – though far from redrawing her as a saint – than the Australian media has ever been able to do.

–

“A Problem Like Matilda” by Michael Schulman

“When it came to turning ‘Matilda’ into a musical, Minchin created a pint-size freethinker in his own image. Overlooked by witless adults, Matilda uses brainpower—which builds into telekinesis—to triumph over stupidity. ‘She wins by being clever,’ Minchin says.”

Tim Minchin wears many masks — or shades of eyeliner, if you will — that all seem to find their way into his music. Schuman draws on Minchin’s witty lyrics to explore the life of our favourite atheist celebre, wordsmith, comic and musician. His most recent and hugely successful endeavour was to translate Roald Dahl’s classic Matilda into a musical, and it serves as Schuman’s point of entry into Minchin’s rising star.

–

“Postscript: Peter Sculthorpe (1929-2014)” by Teju Cole

“In [a] 1999 radio interview, Sculthorpe mentioned the particular honor he felt when, following the death of notable Australians, the obituary features on television would feature fragments of his music. It made him feel like he had become part of the culture in some essential way. All day yesterday, I listened to Peter Sculthorpe. Today, far from Australia, I will again.”

This tribute to the late Peter Sculthorpe exemplifies what The New Yorker does best: making obscure worlds accessible to the reader. In this case, Teju Cole reflects on the sounds of “Australia’s leading composer”, that evoke imagery of harsh desert landscapes but also subtly speak to his interest in Indigenous land rights and celebrate Australia’s proximity to Asia.

–

“Tasmanian Devil” by Richard Flanagan

“Walsh is explicit about what his museum is not: it’s not a rich man gratefully giving back to his community. It’s not an attempt at immortality, as he frankly admits that his collection may be deemed worthless in another decade. It is a theatre of strange enchantments: from a wall of a hundred and fifty-one sculptures of women’s vaginas to racks of rotting cow carcasses; a waterfall, the droplets of which form words from the most-Googled headlines of the day; the remains of a suicide bomber cast in chocolate; a grossly fattened red Porsche; a lavatory in which, through a system of mirrors and binoculars, you can view your own anus; X-ray images of rats carrying crucifixes; a library of blank books; cuneiform tablets; and stone blocks from the Hiroshima railway station, which was destroyed in the atom bombing. “

If Gina Rinehart is famously private, David Walsh is a public enigma. Walsh’s boldest and most famous creation, the MONA in Hobart, has brought attention to his artistic interests, his gambling fortune and his calculated recklessness. Walsh lives directly above his financially and (due to climate change) geographically tenuous creation, which has elevated Tasmania’s tourism profile to the world stage. The piece crescendos nicely, without forcing together Walsh’s many loose ends.

–

“Germaine Greer Is Back” by Margaret Talbot

“More than sexiness, it was confidence that made the Greer on the cover ofLife, and in her public appearances at the time, so alluring. An Australian with a Ph.D. in English from Cambridge, Greer projected a striking self-assuredness as a public intellectual. The certainty of her pronouncements sometimes blunted her analysis, but it was unusual in a woman, and that made it exhilarating; her signature blend of coarseness and erudition made it more so. Gloria Steinem was a more politically efficacious leader. Betty Friedan wrote a better book. But Germaine Greer seemed to lead the most appealing life.”

Margaret Talbot doesn’t pretend to love Germaine Greer. She does, however, have a great deal of respect for Australia’s most outspoken and pioneering feminist. In this short portrait, she reveres Greer’s radicalism and audacity, and simultaneously faults her for it. Greer’s latest book, an account of her project to restore native vegetation on a plot in North Queensland, is welcomed by Talbot as a sign that Greer has her “swagger” back.

–

“Laugh, Kookaburra” by David Sedaris

“Our destination that afternoon was a place called Daylesford, which looked, when we arrived, more like a movie set than like an actual working town. The buildings on the main street were two stories tall, and made of wood, like buildings in the Old West, but brightly painted. Here was the shop selling handmade soaps shaped like petit fours. Here was the fudgery, the jammery, your source for moisturizer. If Dodge City had been founded and maintained by homosexuals, this is what it might have looked like.”

In a familiar trope, though coloured by his prose, David Sedaris’ journey into the Australian bush is also a journey into himself. In getting there, he reflects on family and home and prongs on a burner. There is more sentimentality and less self-depreciating humour than Sedaris fans might be used to, but he is as charming as ever.

–

“The Inferno” by Christine Kenneally

“Residents, seeing huge clouds of dirty orange-yellow smoke looming over the trees, got in their cars and drove, either to shelter in the local football oval or out of town entirely. The local police, firefighters, and emergency workers scrambled to alert people to the danger. Bates and his deputy drove through residential streets with their lights and sirens on, knocking on doors and yelling through the P.A. system that everyone needed to leave. They put together a convoy that was able to exit the town in less than thirty minutes.”

Christine Kenneally, not to be confused with the former NSW Premier, pieces together narratives of the catastrophic Victorian bushfires of 2009. The piece is grounded largely in the small town of Marysville, 100 kilometres north of Melbourne, but pans out to question the way Australia copes with bushfires. It is a raw but measured account of the deadliest fires in our nation’s history.

–

Tom Taylor is a recent graduate of NYU Abu Dhabi, now living in Melbourne. He writes sometimes, in between opening many tabs at once and trying to resuscitate his fast fading laptop.

–

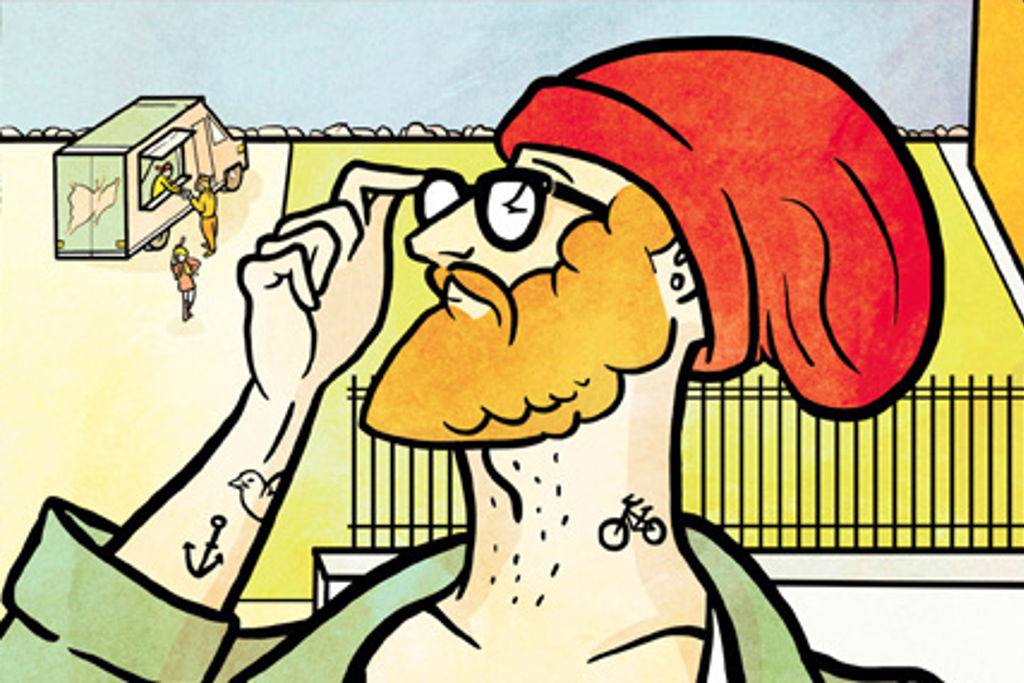

Feature image via Simon Greiner, a Sydney-born artist whose illustration, “Brooklyn’s Eustace”, was the front cover of the New Yorker‘s 2013 anniversary issue.