“That Boy Ain’t Right”: Re-Visiting ‘King Of The Hill’ In The Age Of Trump

King Of The Hill explored the baseness of the American legend with empathy, intimacy, and epiphany. How does that stand up today?

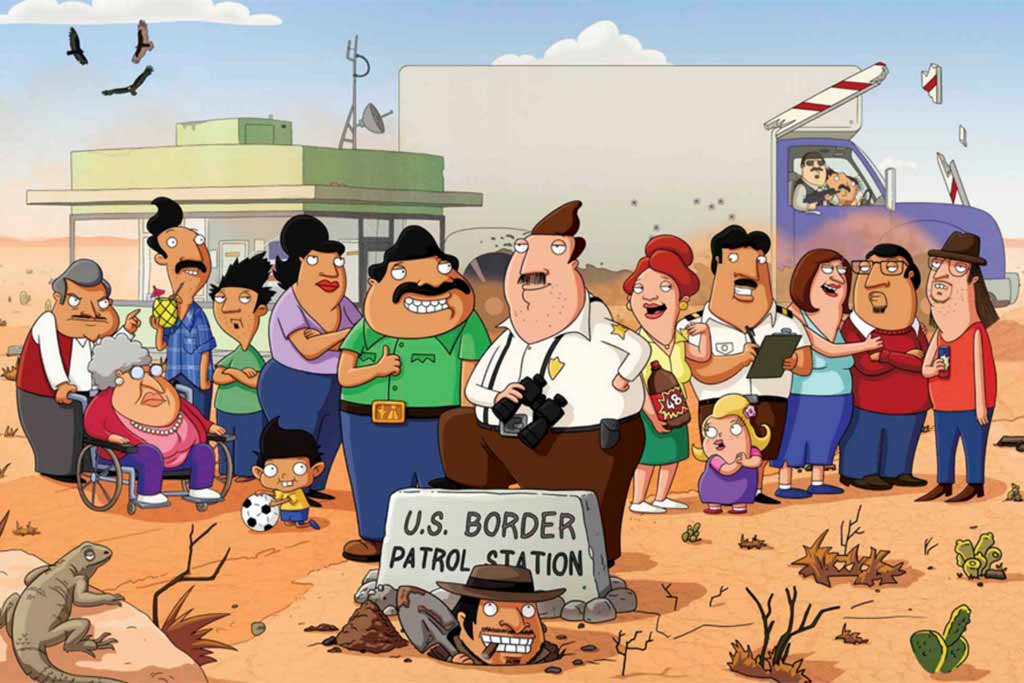

It’s been 20 years since King Of The Hill first aired, and Mike Judge’s seminal satire of the ‘atypical’ Texan family, American class dynamics, and generational rifts, stands as one of the greatest achievements in television.

It’s a slice of animated hyperrealism that extended the banal to ludicrous extremes to mine comic genius. A show driven by exactitude of language, character, and philosophy, King Of The Hill remains one of the longest-running animated sitcoms of all time, and one of the funniest (I’d argue second only to classic Simpsons.)

Ostensibly about the trials and tribulations of humble propane salesman Hank Hill, his extraverted boy Bobby, and over-enthusiastic wife Peggy, King Of The Hill dared to critique the ideal ‘moral conservative’ nuclear family of post-Reagan America. The conflict in KOTH generally stemmed from the friction between Hank’s longing for the mythic greatness and ideals of America’s ‘golden age’, and the postmodern alternative culture of its steady decline. King Of The Hill explored the baseness of the American legend by way of empathy, intimacy, and epiphany.

Hank wasn’t a flag-bearer for conservatism so much as he was for decency. He had a set of ideals instilled in him by visions of the moon-landing, Ford pickup trucks, and John Wayne films. Unlike his son Bobby, Hank was largely devoid of humour or imagination (outside of the world of propane, at least) and the show was more or less an exploration of his path to enlightenment, or his mode of it at least. His values were tested by “jackasses” — yoga instructors, bikies, his friends and neighbours, or Chuck Mangione.

Yet Hank was in awe of anyone he perceived to be his superior, particularly those of a paternal nature. Abusive and manipulative father figures like his WW2 veteran father Cotton (who killed “fiddy men”) and his lecherously corrupt boss, Buck Strickland, directed Hank’s beliefs and self-worth — a fact given equal humour and pathos by Hank’s otherwise headstrong certainty and sense of self.

Outside of these men and others in positions of authority, Hank didn’t tolerate fools, and he especially didn’t tolerate bullies. It’s hard then, for a lifelong KOTH fan, to not think about Hank (and his curb-side mates) in the age of Trump.

What would he make of a man that has hijacked his value system, while simultaneously eroding it? The answer lies in the show’s skewering of men, especially those who struggle to adapt to change.

Morality and Tragedy

KOTH was a show about the fragility of masculinity, the weirdness of male spaces, and the shifting sands of fatherhood. Hank’s father figures (Cotton and Strickland) were ostensibly fitted roles he’d been taught to admire: a war-hero and a titan of industry. Both men, however, failed in the role of father – Cotton spectacularly, Jimmy Carter himself failing to negotiate a peace between the cantankerous “stump” and Hank.

When Cotton has a new child with his young stripper bride DeeDee, he names him GH aka Good Hank. There is something undeniably Trumpian about the troll-like Cotton who, after DeeDee’s breast implants, asks Hank “what do you think of mama’s new tatas?” and tells Luanne “you will never know if you are attractive, it’s up to a man to tell you that”. When he’s on his deathbed, and Hank tells him he loves him, Cotton replies: “You loves me? What kind of man tells another man he loves him?”

Cotton is a vivid example of the underpinning tragedy that made King Of The Hill’s brand of satire so stingingly authentic: the gags and drama are driven by the show’s men, and their inability to access their true selves, swallow their pride, and develop. Hank and his drinking buddies operate as a projection of conservative philosophy’s drive towards stasis.

Hank resists change in all forms, and he’s unwilling to see it: to him, Bill Dauterive is still the beloved high school quarterback, there’s nothing funny about fart noises, and America still leads the world in industry and innovation.

Nowhere is this distaste for change more present than in Hank’s relationship with his outspoken, slightly effeminate, and proudly fat son Bobby. “That boy ain’t right,” Hank would say of his son.

Countless episodes turn on the tension between Hank wanting to be impressed by Bobby, and Bobby wanting to impress Hank. A recurring story arc was Bobby getting into something (hip hop, improv, competitive dog dancing), loving it, and Hank trying to convince him it was bad.

When Bobby joins the soccer team he’s surprised that his father, who is constantly trying to make him an athlete, doesn’t approve. It culminates in this exchange:

Hank: “Bobby, I never thought I’d need to tell you this, but I would be a bad parent if I didn’t. Soccer was invented by European ladies to keep them busy while their husbands did the cooking.”

Bobby: “Why do you have to hate what you don’t understand?”

Hank: “I don’t hate you, Bobby.”

Bobby: “I meant soccer.”

Hank: “Oh. Oh, yeah, I hate soccer. Yes.”

In the episode ‘Bobby Goes Nuts’, Hank is stoked to hear that Bobby has learnt self defence, and is standing up to his bullies. He is horrified to discover however that Bobby (who attended a women’s defence class) is doing this by kicking everyone in the nuts, and screaming: “That’s my purse! I don’t know you!”.

In the episode ‘Now Who’s The Dummy?’, when Hank initially disproves of his burgeoning interest in ventriloquism, Bobby creates an “all-American boy” persona for his dummy named Chip — replete with letterman jacket and buzzcut — so he can communicate about sport with his dad. Hank, being an essentially compassionate person, usually comes around and accepts Bobby, quietly confessing to himself that things are different: there is no ideal ‘American boy’ anymore.

KOTH explores the emotional absences that pervade the space between fathers and sons, and in doing so draws a link between those shortcomings, and societal shortcomings.

Hank’s absence of a caring father drives him to paternally nurture others, even when it’s not in either parties’ interest. We see this in his relationship to his desirous trailer-park-evangelical niece, Luanne, who communicated with her emotionally stunted “Uncle Hank” via finger-puppets. Hank was brother and father to his lifelong friends Dale, Bill, and Boomhauer, who he had to constantly navigate through life’s harsh realities.

Boomhauer was a charismatic womaniser who failed to settle down, Bill was a record-holding high school athlete turned weeping divorcee and army barber, Dale was a delusional conspiracy theorist unable to recognise the conspiracy within his own house: that his (clearly Native American) son Josef is the biological son of his wife Nancy’s “masseuse”, Johnny Redcorn.

You have to understand these ideas of manhood and fatherhood to understand where the show stands politically.

Then there is Peggy, or as Cotton calls her, “Hank’s wife”. Peggy is unlike any other sitcom mother: never sexualised (except for her disproportionate size 16 ½ feet), Peggy is a dilettante determined to the point of delusion. Peggy has zero self-doubt and (unlike Hank) absolutely no shame.

The polar opposite of the Marge Simpson-style housewife viewers would expect a character like Hank to be married to, Peggy rarely attracts Hank’s ire despite sharing so much in common with those who do. Peggy knows herself, and Hank respects that.

In many ways, her asexuality and brash machismo makes her the confident and accepting father figure Hank secretly aspires to be. When Bobby downs Hank in his nut-kicking rampage, it’s Peggy that stands up to him, saying: “I believe you will find that I have no testicles, where’s your secret weapon now, huh?”

You have to understand these ideas of manhood and fatherhood to understand where the show stands politically, especially in relationship to the identity/brand of the Trumps. Hank and his family are essentially polar opposites of the Trump dynasty. Hank is hard-working and kind; Peggy is ‘homely’, driven and proud; Bobby will perform Slim Shady with shadow puppets, Luanne marries Lucky (who “slipped on pee pee at the Costco”) for true love, even though it means she won’t escape the cycle of poverty.

They are virtuous characters whose eccentricities lend strength to the internal moral logic of the show. Hank principles are, unlike Donald’s, unflinchingly consistent.

Making America Great Again

It’s the rest of the cast that might have become #MAGA warriors. Bill and Boomhauer are the type of isolated sad-sacks that find comfort in Trump’s brash machismo. Hank’s Laotian neighbour Kahn, the archetypal hard-working immigrant, constantly abandons compassion for the necessary cruelty of opportunism: Trump is the kind of character he’d suck up to at his country club, Nine Rivers.

Then there is Dale, the pocket-sand wielding paranoiac who peddles conspiracies and whose tangeants read like Breitbart abstracts. “Tell you what it is: it’s your quote un-quote pollution control. I heard on talk radio you don’t even need ’em. It’s just the latest Nazi government plot. Open your eyes, man,”

You can see Dale on Twitter, lambasting “fake news” behind a Pepe display pic. There is of course one greatly prescient irony with Dale: he’s known to everyone but himself, being a ‘cuck’.

Trump is the exact kind of charlatan that the KOTH characters are consistently screwed over by, and the kind Hank constantly butts heads with. The show is driven by a desire to show the hilariously bleak irony of people like Hank and his friends supporting a philosophy and brand of government that so consistently screws them over.

To Judge, that is the essential farce of modern (post-Nixon) American conservatism, and we see it across the spectrum of his work. He extrapolates the folly of this relationship with characters who — in their own way — partake (Hank), protest (Daria), or subvert (Beavis and Butthead) this cycle of abuse and co-dependency.

With KOTH characters, especially Hank, it’s not the politics or the ideas that would lose Trump a vote, but the man himself. Like all things in the show, what makes a “good man” is rooted in ideas of paternalism.

KOTH prophesied the new-wave of nationalists, hacks, experts, and snake-oil salesmen that are currently carving up the US.

In my favourite episode, ‘The Perils of Polling’, Bobby and Hank are invited to meet then Governor George W. Bush after Bobby saves a diving carnival pig from drowning (“pig heart-transplant, or pig-saving boy?” Bush asks an aide before meeting Bobby). When Bush gives Hank a limp handshake, Hank is mortified. His entire world-view collapses. He obsesses over tapes of Bush shaking hands, noting the faces of other victims as they shift through “happy, surprised, disappointed”. The sliding approval ratings that follow the election of a phony.

Bush, himself the product of daddy issues, failed the ‘real man’ test. In that moment, Hank saw behind the curtain and realised (again) that he’d been sold a lie: that his candidate was akin to filthy inefficient charcoal, not beautiful clean-burning propane.

In its joke-packed morality plays King Of The Hill was able to elevate and accentuate the essential dilemmas of right-leaning white working class folk in America. An extended exercise in postmodern humanism, King Of The Hill was quietly bipartisan: its distillation of men to the bare brittle essence prophesied the new-wave of nationalists, hacks, experts, and snake-oil salesmen that are currently carving up the US.

King Of The Hill made the point that the system was as absurd as the jackasses that operated within it: that the capability of paternal entities like Congress or the Presidency are dependent on ideas of government, free will, and manhood that are, fundamentally, bullshit.

There’s little doubt that both Hank and Trump are driven by a deep aversion to change and nostalgically skewed desire to “make American great again”. Trump, like Hank, had a distant bullying father who seems to have shaped his views of masculinity. Hank, unlike Trump, has taken on the fatherhood of many with patience, benevolence, and stoicism.

There’s no question that Hank Hill would not have voted for Donald Trump. He’d take one look at him and say, “that boy ain’t right.”

–

Patrick Marlborough is a writer and comedian based out of Fremantle. He tweets at @Cormac_McCafe.