Is ‘Lust For Life’ The Album Lana Del Rey Has Been Trying To Make Her Whole Career?

We review the latest from Lana Del Rey.

When Lana Del Rey sings “Look at you kids with your vintage music,” the first line of her new album Lust For Life, who is she singing to? It could be to her fans – assumedly the same nostalgia-fetishising crowd who shop for ‘reclaimed’ vintage at Urban Outfitters and reblog pictures of pastel wallpaper on Tumblr – but it could just as easily be directed to herself, or a former version of herself, at least.

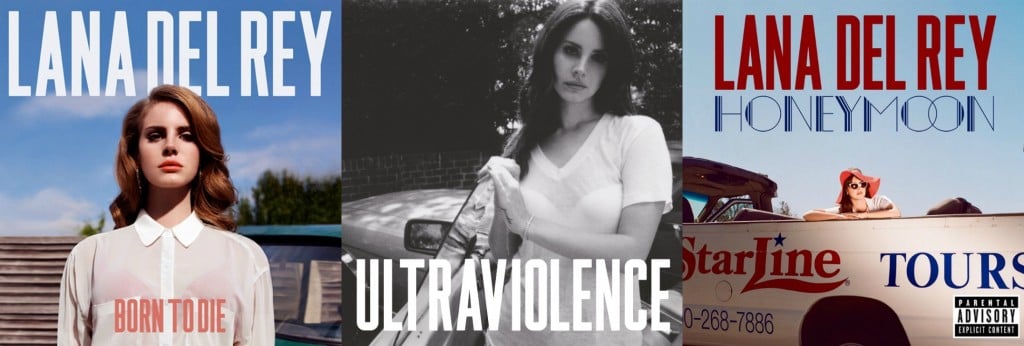

When we first met Del Rey on 2012’s Born To Die, she was a confused would-be popstar name-checking Marilyn and cosplaying as Jackie O, subbing in ‘vintage’ filtered music and production effects to mask the fact that outside a couple of huge singles, there wasn’t really much there.

Over her two Born To Die follow-ups, 2014’s Ultraviolence and 2015’s Honeymoon, her dinky vintage aesthetics grew from a framing device into something more resembling an edifice. Her work, once pleasurable to listen to but cloyingly shallow, became more richly textured and nuanced once she departed from her hamfisted attempts at pop.

And truth be told, Del Rey truly did depart entirely from pop on her second and third albums. Ultraviolence and Honeymoon weren’t concerned with courting radio jockeys like Born To Die was; instead, they were long and languid collections of torch songs, filled with tales of malaise, violence and betrayal. It was on these records that the depth of the Lana Del Rey project came into full view; Del Rey was less an aspiring popstar and more an auteur trying to paint a portrait of fatal and all-consuming lust, wealth and fame.

Lust For Life represents Del Rey’s attempt to reconcile the pop instincts that made Born To Die the fifth-best selling album of its release year with the shrewd artistic vision that pieced together Ultraviolence and Honeymoon.

It’s something of a commercial course correction, too: sales figures suggest that Del Rey’s embrace of six-minute torch songs definitely alienated some more casual fans. This attempt to reconcile what seem like two fundamentally different approaches to music-making results in an album that’s good, but not nearly as satisfying as her previous artistic endeavours.

“Even the poppiest songs of the sixteen tracks on Lust For Life would struggle to find radio rotation”

Even the poppiest songs of the sixteen tracks on Lust For Life would struggle to find radio rotation, though — Del Rey’s method for broadening the appeal of her music is mostly just to add a beat, a hook, and keep the running time under four and a half minutes, a significant concession for her but still barely a concession.

The album’s title track, a Weeknd collaboration, is the most obvious contender for a Big Single, but it’s oddly staid; it feels more like a Born To Die outtake than something representative of either The Weeknd or Del Rey’s current potential. The hook meanders, and the lyrics — which basically range from “My boyfriend’s back, and he’s cooler than ever” to “They say only the good die young / That just ain’t right” in emotional depth — deal in the kind of triteness that both artists stopped doling out two years ago.

‘Lust For Life’ is the first of five collaborations on the album, and the rest tend to fare a lot better. ‘Summer Bummer’ and ‘Groupie Love’, a pair of A$AP Rocky collaborations sitting in the centre of the album, are stunning, and give Del Rey’s sound a sense of relevance without contrivance.

“While she’s generally known for lighter songs, it’s consistently her dread-ridden tracks that are most striking”

‘Summer Bummer’, also featuring Playboi Carti, is one of Del Rey’s few hip-hop tracks to have actually been produced by a rap producer (in this case, Boi-1da) which means it’s a lot less heavy handed than her other tracks which prominently feature beats.

The song is creepy and claustrophobic, a summer jam that feels more appropriate for a humid city summer than a beach getaway. It’s on songs like this that Del Rey’s gift for conjuring unease comes to the fore. While she’s generally known for lighter songs, it’s consistently her dread-ridden tracks that are most striking.

The album’s other two collaborations – ‘Beautiful People, Beautiful Problems’, featuring Stevie Nicks, and ‘Tomorrow Never Came’, a duet with Sean Ono Lennon – fit more broadly into a cache of tracks on Lust For Life (along with ‘Love’ and ‘Get Free’) on which Del Rey deals with legacy, time and her place in popular culture at this particular moment.

‘Beautiful People’ finds an interesting angle in the way it interrogates the outlook of Del Rey’s oeuvre to date. “We complain about how it’s hard to live, it’s more than just a video game,” she sings, making reference to the song that started her career. The song ends with Nicks and Del Rey singing “We’re just beautiful people with beautiful problems,” over and over, the insignificance of the phrase hitting harder with each repetition. Is the track satire, or is Del Rey playing it straight once again, as she liked to do on Born To Die? It’s hard to tell – the lyrics, relatively spare compared to an ordinary LDR song, offer few hints.

‘Tomorrow Never Came’, a sweet but fairly standard song, brings Del Rey’s self-spun narrative full circle. Ono Lennon doesn’t add a huge amount to the song, but his presence allows Del Rey to deliver one of her best (and most absurd) couplets yet: “Lennon and Yoko, we would play all day long / “Isn’t life crazy?” I said, “Now I’m singing with Sean.”

It’s a weirdly surreal moment – when Del Rey sings about her icons, she rarely makes reference to time or place, and it often feels like she’s inserting herself into past narratives. ‘Tomorrow Never Came’ blurs this, as she acknowledges her place in the present for the first time. It’s a clever line, and one that brings questions about identity, and whether she’s playing a character, back to the surface.

After a set of tracks that seem to suffer from identity trouble, Lust For Life ends with three songs that feel like classic Lana: tragic, languorous and beautiful.

Del Rey’s music is often described, disparagingly, as mood music without any real innovation or uniqueness. These tracks push back against that, the musician finding new ways to frame her sound. On ‘Heroin’, she experiments with vocal modulation, her voice lifting to a thrilling yell at the song’s peak. ‘Change’ and ‘Get Free’ once again find Del Rey questioning everything that she’s been for her audience until this point.

She’s said that Lust For Life is her first album for herself, as opposed to for the fans, so it’s interesting to hear that manifest in self analysis: she sings “Change is a powerful thing / I feel it coming in me,” on ‘Change’, hinting at a change of pace for album five, and on ‘Get Free’, the album’s final song, she finally admits that she wants to get “out of the black, into the blue.”

All of this makes Lust For Life an album that seems ultimately concerned with settling scores: between Del Rey and her fans; her label; and herself. It feels like a bloodletting — a way for Lana Del Rey, an artist entrenched in her own aesthetic like no other, to finally remove herself from it.

—

Shaad D’Souza is a freelance writer from Melbourne. Follow him on Twitter here.