The Problems And Privilege Of Living With An Invisible Disability

"I often feel guilty or not completely seen."

On the third day of Year 7, my English teacher asked me to get up in front of the class and out myself.

I stood up and explained that I was vision-impaired and that I had albinism. I reluctantly demonstrated my monocular (a singular binocular that I needed to use to see the board) and rushed to get the whole thing over and done with. I don’t really know what my classmates thought, and to be honest I was probably too flustered to pay attention. But I know that they weren’t expecting me to be an albino or have a disability.

Throughout my life, whether intentionally or not, I have developed a series of tricks that make my albinism and disability invisible. I use these tricks to ‘pass’ as able-bodied, to avoid drawing attention to myself and to limit any marginalisation I might experience because of what my body cannot do.

This experience of ‘outing’ myself as a person with a disability and specifically a person with albinism has continued through my life. Because I don’t fit the typical Da Vinci Code murderer albino vibe, I pass as a person without a disability — at first glance, there is nothing about me that would suggest that I’m not able-bodied.

I come out when I start a new job, when someone notices me holding my phone really close to my face, when I start dating someone new and my eyes shake because I am nervous, when someone asks me why I am so white (yes, really).

Just, no.

The invisible nature of my disability gives me a ticket into the able-bodied world — except that once I get there, I can’t see and I will probably get severely sunburnt.

People with albinism, or who are albino, are characterised by having super white hair and skin and often having light blue or purple-y eyes. It’s happens because of a recessive gene that means you don’t produce the pigment melanin when you’re cooking in utero. What many people don’t know is that you also need melanin to properly develop your eyes, so most people with albinism are vision-impaired or partially blind.

My eyesight can be rather shit. I’m too blind to drive, the text on my phone is as big as your retired dad’s and I’m really photophobic, which means my eyes are sensitive to light. I also have a nystagmus which means my eyes shake to focus; they do it more when I am nervous or upset, which has always exacerbated my nervousness in intimidating situations.

While I am very pale, there are definitely many who would look more obviously albino than me. My colouring is probably most similar to someone like Cate Blanchett (whatababe), who doesn’t have albinism. I hit the fake tan pretty hard as a teenager but now I try to work my paleness in with my whole tonal linen Melbourne aesthetic. I experience some frustration and limitation because of with my eyesight. But I also get half-price taxis subsidised by the Victorian government so I suppose it all balances out.

Having an invisible disability means I have often sat uneasily between the able-bodied and non-able-bodied communities. Even as a kid I was the most sighted kid at the blind school and the blindest kid at the mainstream school. I was too independent (read: stubborn) to be eligible for any accessibility funding but I still missed out on lots of visual cues in the classroom.

I often feel guilty or not completely seen.

This in-between space — while nuanced and unique for each person — is a space I imagine might be familiar to others who can pass as someone with a privileged body. These are the bodies who have what the world often considers as having the ‘default’ experience (a heterosexual, cis-gendered, white person for instance) who are able to move more easily through the world because some aspect of their sexuality, race, gender identity or any other signifier of who they are isn’t immediately visible.

Being able to pass can feel uneasy because it forces you to confront the things you have access to that others in your community do not. I often feel guilty or not completely seen when I think about my privilege in this regard. Until recently, I would look at my very white body and be self-conscious and aware of the disadvantages I experienced as an albino. Naively, I was failing to see that because I pass as able-bodied and non-albino, the colour of my skin equates to straight-up white privilege, which I have loads of. I am sure that people with albinism who are also people of colour have a particularly difficult time reconciling these parts of their identity. The extent to which they pass as racially or culturally white would impact this dramatically.

There are definite advantages that come from passing as able-bodied. I get to come out when I want and I don’t experience the immediate disadvantages that others who live with a disability might. But it can also be painful because I am often on edge as I wait for someone to notice, for the invisible to be made visible and, despite my pride in being someone with albinism and with a disability, I still feel vulnerable every time I am found out.

It’s complex and it’s always changing, but at least I have my half-price taxi card.

—

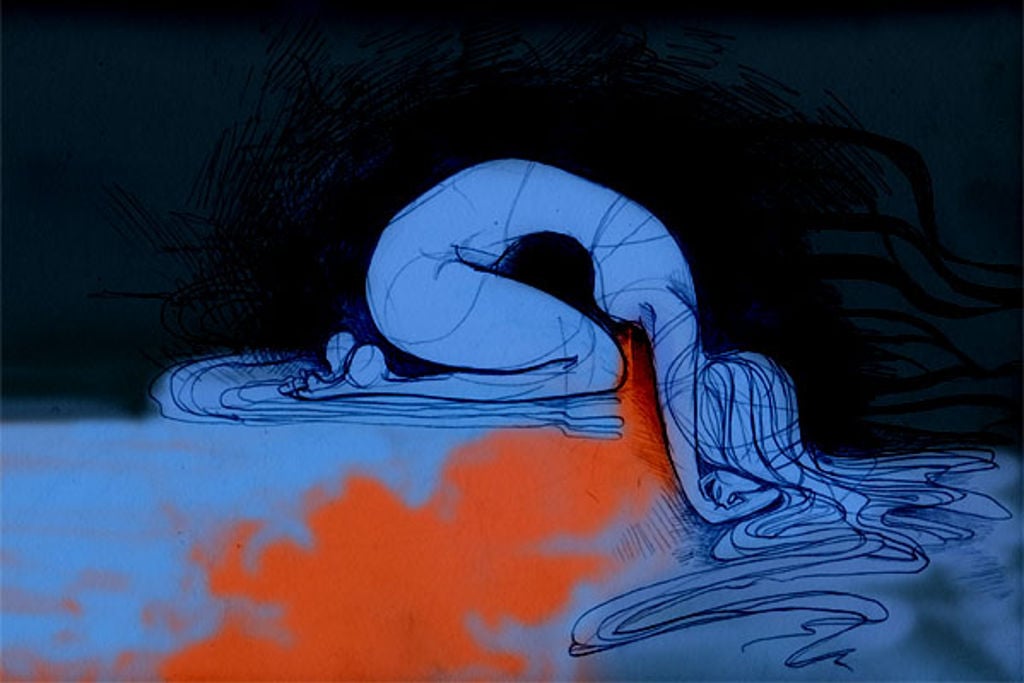

Image by Mo Riza via Creative Commons/Flickr.

—

Brigid Canny is a filmmaker and facilitator loving all things social impact storytelling. She tweets about women and feelings from @brigidcanny.

—

Brigid was also a delegate of Junket 2016 where she ran a session on this topic. Read more thoughts and features from some of our other 200 delegates here.