Are TV Recaps The Reviewing Equivalent Of Premature Ejaculation?

Scoff all you like, the recap is part of how we watch TV now.

Recently Pamela Adlon, star of Louie and Californication, dissed TV recaps in an interview with Vulture:

“I love the conversation – I think it’s wonderful – I just think people are premature-ejaculating their opinions. I liken it to reading a book, and you’re halfway through and you put it down, and you say, ‘This is what happened in the book so far, and you know what? If this doesn’t happen I’m going to be so upset.’”

I don’t watch Louie, but having recapped Game of Thrones for Junkee, I obviously have some professional dignity invested in conversations about the genre’s value.

I think I realised why I hate tv recaps: they resemble bad student essays that are merely descriptive rather than analytical.

— Matthew Sini (@MatthewSini) June 17, 2014

Like any cultural criticism, recaps can be done badly. But that shouldn’t damn the whole genre . Recaps are a satisfyingly immediate way to express and analyse the experience of watching television; and their ability to identify a TV zeitgeist while it’s fresh should be cherished, not condemned.

–

What’s The Difference Between Recaps And Reviews?

Recaps are often dismissed as the idiot cousin of reviews. It doesn’t help that the recap form emerged from teen soaps, which are themselves deemed debased.

However, the best recaps are reviews. With enthusiasm and goodwill, critically and thematically, they analyse narrative, character and mise-en-scène. They discuss the episode in relation to previous episodes and to other texts and contexts.

Recapping is a form, not a style: a reviewing genre that follows a TV series episodically. It aims to spark water-cooler-style discussion among people who are also watching the show. I find it enriches my favourite TV shows to read how the critics I respect – and their comments sections – interpret each episode. It prolongs the pleasure of spectatorship, adding new insights that mightn’t have occurred to me.

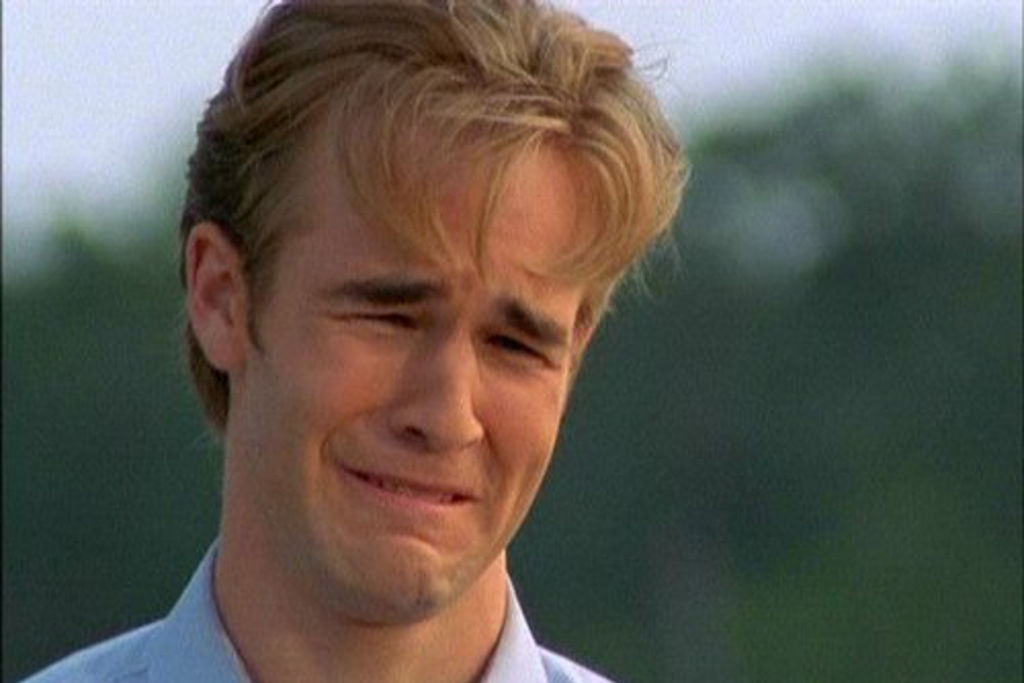

The website Television Without Pity – originally named Dawson’s Wrap after the series it first recapped – helped define the recap as a detailed summary of an individual TV episode. Some of its recaps weren’t reviews, but were designed to help viewers who’d missed an episode catch up with a show’s plot. But TWoP also positioned the recapper as “a hybrid fan/critic/hater” with a snarky, superior voice. The notion that recapping is about cracking jokes, and the broader hobby of hate-watching ‘trash TV’, is probably TWoP’s greatest legacy.

I don’t like this kind of recap, because it isn’t a review. Its mean-spiritedness cheapens the pleasure of culture, which surely we’re drawn to from a basic human impulse towards meaning-making. What sad, stunted lives we lead if we approach culture snobbishly, and reduce its meaning to ‘lulz’.

–

Can We Legitimately Analyse A ‘Work In Progress’?

If, as Adlon told Vulture, a season of a TV show is the ‘work’, should we – the critics – reserve our opinions until we can watch an entire season at once?

Apart from the commercial reality that media organisations want to convert their readers’ interest in current shows into megaclixxx on their TV coverage, retrospective criticism has a substantially different aim. It prioritises posterity – a show’s ability to capture a zeitgeist or influence those that followed it – whereas for most viewers, that show is strongly embedded in the fabric of everyday life.

Serial TV is more than just a longform movie or a visual novel, because its narratives are structured to include time. Cliffhangers and revelations are carefully planned for season openers, finales and the increasingly popular ‘mid-season finales’. Actors and writers come and go offscreen, and stories mould themselves to the uncertainty of renewal or cancellation. (Remember how insane the Australian ’90s adult soap Chances became in response to poor ratings?)

In April, The Week claimed recap culture is hurting television. “Recaps began to double as proving grounds for theories, as if a TV show were a puzzle that needed to be solved,” argued writer Chris O’Shea. Similarly, Adlon wishes that, rather than speculating on what they’ve just seen, Louie recappers would just chill out and let Louis CK develop his characters naturalistically.

“I know that one thing that motivates Louis and drives him is characters that don’t explain why they do what they do. You just see things happen and play out, and you don’t get a neat little button at the end of it.”

Jaded former recapper Rich Juzwiak argues – and I can testify – that it’s really, really hard to respond to a show originally and incisively every single week, to the compressed deadlines recaps demand. TWoP’s legacy means readers often treat recaps as entertainment rather than criticism. And because recaps are ephemeral, they can feel insubstantial and thankless, making the recapper feel like a performing monkey.

It’s tempting to retreat into summary and snark, or to hang your recap on the dramatic ‘hook’ of a shocking moment, extrapolating what it ‘means’. Sometimes, you identify something as more, or less, significant than it turns out to be.

Like Game of Thrones, Louie had a rape controversy this season, and both shows used subsequent episodes to insist that what recappers interpreted as nonconsensual was more nuanced. But while Game of Thrones folded its rape scene into a broader story of ‘those kinky, passionate Lannister twins’, Louie met its critics head-on two episodes later in a meta-commentary on ‘offensiveness’.

That doesn’t mean recappers reacted ‘wrongly’. The recap genre is ideally positioned to capture TV’s contingency, and to reflect viewers’ anticipation. Still, good recappers should resist being buffeted by the storms showrunners actively build into their stories. As Matt Zoller Seitz writes at Vulture, “The piece is, first and foremost, a description of the contents of the writer’s mind. If it’s empty, the writer is basically fucked.”

–

Recaps Both Challenge and Reinforce TV Auteurism

When we grumble that recappers impatiently second-guess showrunners’ creative decisions, we’re really complaining that recapping undermines the mystique of TV auteurism. But what if ruminating on the intentions of an auteur is precisely what codifies a series as ‘quality television’?

David Lynch’s Twin Peaks, hailed as the catalyst for today’s TV golden age, expressed Lynch’s already established sensibility. His fans were used to asking themselves what his films ‘meant’, and Twin Peaks was itself a show about searching for answers beyond the quotidian.

The X-Files, meanwhile, actively encouraged viewer speculation because it was situated within America’s pre-existing conspiracy culture. It was one of the first network dramas to embed episode-long procedural stories within larger, multi-season narrative arcs – not because of creator Chris Carter’s autonomous genius, but because viewers wanted more to speculate on. Carter says he developed this structure after a fan wrote to tell him: “[We] like the episodes that involve Mulder and Scully and their relationship and their lives and not the ones that are strictly procedural and case-driven.”

Otherworldly mystery was also the engine of Lost (created by Jeffrey Leiber, JJ Abrams and Damon Lindelof), of Daniel Knauf’s sadly under-appreciated Carnivale, and was seized upon fetishistically by recappers of Nic Pizzolatto’s True Detective. We’ve learned to approach these complex TV series with awe, to scrutinise them in minute detail, and treat showrunners as oracles.

What did David Chase mean by the final moments of The Sopranos? Matthew Weiner is the Buddha of Mad Men, endlessly interviewed by supplicant TV writers to whom he responds enigmatically. And who will the mischievous George RR Martin and his junior partners Benioff and Weiss ruthlessly kill off next on Game of Thrones?

Reading those entrails, seeking those answers, is the role of the recap. Not-knowing, yet striving to find meaning, and reinterpreting it over time as the story develops. This is how we experience TV. And it’s that immediate engagement – rather than politely waiting until the DVD comes out – that makes recaps vital and valuable.