How To Give A TED Talk Without Even Trying

If you specialise in mindless #inspiration, pseudoscience and feelgood nonsense, maybe you can give a TED Talk too.

Three little letters,

a paradox to some.

The worse that it is,

the better it becomes.

–

The answer to this riddle is supposed to be “pun” but could just as easily be “TED” — the Technology, Entertainment, Design conferences notionally created to enrich our understanding of the world, but which often just confound us with doublespeak, and stroke the egos of rich wankers with a product to flog.

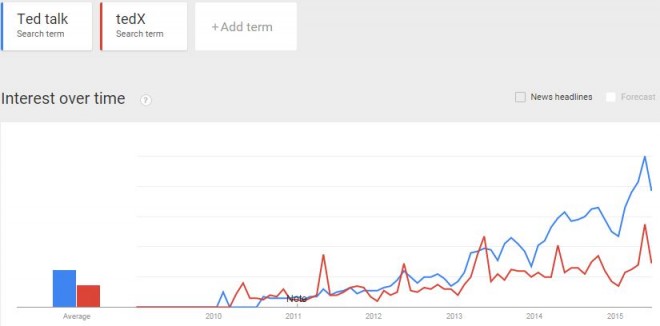

Terrible as they are, TED talks served a valuable end in that they triggered a satire boom. Parody after parody, these talks have been ferociously lampooned for at least five years. You’d think TED’s credibility would be shot. Yet people continue to pay $8500 to attend these glad-handing gabfests, and many continue to watch online for free. Google Trends indicates a clear upward trajectory in the global popularity of both “TED talks” and “TEDx” as search terms.

Australia, shame on us, displays the fifth-highest regional interest, with searches for “TED talk” skyrocketing from a trough in January 2015 to a record high in March, when Monica Lewinsky delivered her TED talk entitled “The price of shame”. Funnily enough, this correlated with a spike in regional interest for the search term “blowjob,” which hit 93% of its maximum popularity over time. Coincidence? Double shame, Australia.

Worst of all, an auxiliary service economy has cropped up around TED, as opportunistic business-savvy organisations devise exxy short courses to teach middlebrow windbags “how to give a TEDx-style talk”.

If there’s one thing that annoys me more than TED talks, it’s people making money off of spurious “workshop” events.

And if, in fact, the honest goal of TED talks is to communicate “ideas worth spreading,” then monetising their proper instruction seems not only cynical but dumps a great big commercialised roadblock in the way of progress.

So, in service to the open-source knowledge economy, I’ve created this instructional guide — totally gratis and with no strings attached — on the three most effective tropes and strategies of the world’s premier narcissists.

–

Give the illusion of sense, without needing to make any

The best way to do this is to link your argument back to brainology, or, as it’s known in boffinese, “neuroscience”.

Dr Rod Lamberts is deputy director at the Australian National Centre for Public Awareness of Science. He says that, in popular media, neuroscience tends to become “no different to any other mystical art”; that people with a political or business agenda exploit it is as a modern form of astrology or fortune telling.

It works like this…

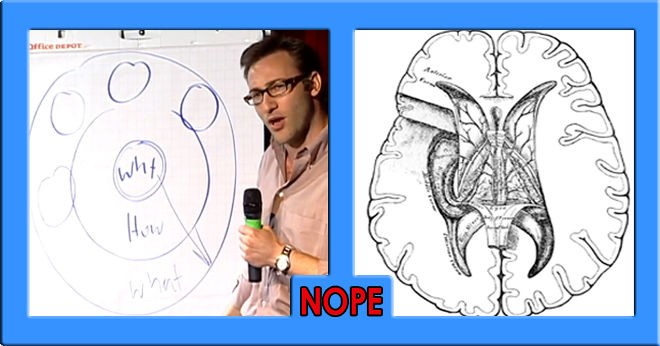

In 2009, the year TEDx launched, “leadership expert” Simon Sinek delivered the most-watched TEDx talk ever — 22.5 million views, and counting. In this texta-and-easel-based homage to the The Secret, Sinek introduces us to “the golden circle,” which is supposed to explain “how great leaders inspire action,” but which Sinek only ever uses to explain why Dell couldn’t sell MP3 players.

Pointing to a hand-drawn diagram, Sinek argues his theory is not only instrumental but also scientifically sound because “the golden circle” sort of resembles a cross-section of the human brain.

The audience coos: Ahhhh, yes, the brain! I’ve heard about that. It’s where all your smarts are ideated to then go “swoosh!” down the mind-pipes, into the vocalator and out your talky hole.

Damn, he’s charismatic! But how does he do it?

Using a term coined by Stephen Colbert, Lamberts explains that pseudo-neuroscience sells because “it’s got a lot of ‘truthiness’ about it”. Anything purporting to tap into the way our brain works is rich fodder for confirmation bias “because of how ‘sciencey’ it looks, and the ‘truthiness’ of the science … So you strap that to our already strong opinions about why people do things, add your values and your politics — it’s amazing, there’s so much you can do with it.”

In short, “neuroscience” is to nerd-chic nontrepreneurs what “Minister for Women” is to Tony Abbott: a hollow slogan, to disguise an inferior product. Apply liberally.

–

Don’t actually solve problems (or, Damn the info, focus on the ‘tainment)

Solving problems is boring. People who have time to go to TEDx talks don’t have problems, anyway. Well, actually, they have one problem: they’re bored with their lives. But you know what’s fun? Dreaming up highly imaginative, but wildly impractical tech-only solutions to social and political tragedies.

I recommend starting small. Try focusing on local, Australian problems; especially problems of the political or business elite (that’s where the venture capital is). You could look at how cabinet leaks continue to make the Prime Minister look stupid, and solve that with a bit of Wonderland technology. E.g. try retaining his ministers’ cerebral data via a neural implant that beams their memories straight to Peta Credlin’s iPhone. Real-time surveillance = real-time justice.

The two-birds-one-stone approach is also a winner. Say, drug dependency and malnutrition? Try a pro-biotic, kale-based methamphetamine. It’s like ice but good for you.

You’ll also want to pepper your talk with strings of highfalutin, techno weasel words (Don Watson can swivel). Here’s some I prepared earlier:

- Seamless paradigm shift

- Next gen data-mining netiquette

- Disruptive real-time podcasting for the Global Citizen

- Cross-platform, mobile-modular, algorithmic and immersive crowdsourcing served with slow-roast pulled pork on a bed of buckwheat.

Feel free to use without attribution or understanding.

–

Win hearts, forget minds

In March this year, former prime minister Kevin Rudd delivered a talk that captured the very best of TED’s bourgeois optimism. On the future of US-China diplomatic relations, Rudd’s talk was rambling, indulgent, littered with off-key dad jokes and, for one very brief moment, genuinely articulate and perceptive.

Director of the Lowy Institute’s East Asia Program Dr Merriden Varrall reviewed his talk thus: “Rudd didn’t quite nail it … he went a bit too far in the oversimplification and lost a bit of the message.” (Note, when Varrall says he “didn’t quite nail it” and “went too far”, she’s speaking as someone more interested in good policy than good TEDding. Oversimplification is a TEDder’s best friend.)

Varrall agrees with Rudd’s contention that US-China diplomacy can only initiate from a mutual recognition of each other’s nationalistic peculiarities. Varrall adds that this would help to attenuate harmful, bilateral misperceptions; “Correcting misperceptions is an integral part of international relations and politics. Misperceptions pose a high geo-political risk.”

“So when Rudd started speaking about how we need to stop thinking in terms of China’s dream versus the US’ dream, and we need to start thinking more collectively, he was making a very good point,” said Varrall.

But audiences can only stand so much detailed programmatic specificity before their minds start to wander. Where’s the #inspo, Kevin?

Thankfully, Rudd lays it on thick when he extolls his 2008 apology to the Stolen Generations. He says this symbolic act of kindness ushered in a “new beginning, because we had gone not just to the head but also the heart,” and that we must do similar in the case of the US and China.

Never mind, then, that rates of hospitalisation for self-harm continue to increase amongst the Australian indigenous population; adult imprisonment rates worsen; and many key indicators of “closing the gap” actually point to its widening. Our minds could never abide this blatant lack of progress, but our hearts were sated. So that’s nice.

Riffing on the feel-good qualities of the apology, Rudd tacitly exhorts the golden rule of TEDding: first, take learned insight, and then sandwich it between irrelevant anecdotes and quixotic nonsense, leading to a soft-brained, heart-warming conclusion.

In the end, the difficult project of detente is reduced to a loose vision of, as Rudd describes it, “a dream for all human kind”. How do we get there? We “take a leap of faith, not quite knowing where we might land”. TED audiences love a simple visionary.

Ultimately, the key to unlocking your true potential as a TED-quality speaker is, as Associate Professor at the University of California Benjamin Bratton has it, “taking something with substance and value, and coring it out so that it can be swallowed without chewing”.

Class dismissed.

–

Dan Wood is a freelance writer, croissant expert and visionary solipsist. He has written for Crikey, The Lifted Brow and Daily Review. When he’s not eating avocado, he works at Crikey as a subeditor.