How Do We Get Australia Talking About Missing Persons?

What would you do if a loved one disappeared?

In November 2015 we held our first youth unconference, JUNKET. Since then, we’ve shared thoughts and features from some of our 200 delegates on the topics they raised. This, from Emma Beckett, leads on from a session she ran about how to raise public awareness about missing persons.

–

Over 38,000 people are reported missing in Australia each year. That equates to one person every 14 minutes, or over 100 a day. Thankfully, most of these people are located quickly, but thousands remain missing long-term. Many are never found.

Maybe that number doesn’t sound very big to you. Maybe you have never personally known anyone who went missing. But whether or not someone is missing for a long time or a short time, it has a significant impact on the missing person’s friends, family and others.

For every missing person, at least 12 people are directly impacted – that’s nearly half a million Australians every year. These impacts can be emotional and psychological, may be related to finance, quality of life, health or relationships. For many of these people the burden is long lasting.

Like everything devastating in life, you probably don’t think this could happen to you, or your family. But just stop for a second and think: what would you do if one of these missing people was someone you knew? Would you know where to start? Who would you turn to for help?

–

Knowing Where To Turn

Loren O’Keeffe can answer these questions from experience. One day in 2011, Loren’s brother Dan simply left the family home, taking no possessions, and never came back.

In the first few days, the O’Keeffes didn’t know what to do, or where to turn. Dan was reported missing to the police, but as he was an adult male and there was no suggestion of foul play, his case was considered non-suspicious – police simply told the family to do whatever they felt they should do.

So Loren, running on instinct alone, took matters into her own hands and started an online campaign to find her brother. Three days after Dan went missing, she made a Facebook page, a Twitter account and a website. That spread to billboards, bumper stickers, and posters being distributed by people all over Australia.

The massive reach of the online campaign (the Facebook page has more than 63,000 followers) translated into interest from traditional media, and soon she was putting out press releases and doing newspaper, radio and TV interviews. One of these media appearances led to the only confirmed sighting of her brother since he went missing.

The exposure didn’t just raise an interest in Dan’s case; it made Loren a go-to for people in similar situations. Although Loren figured out her Dan Come Home campaign strategy by herself, she says she “was frustrated that thousands of people still had no guidance in a context where time is really of the essence”.

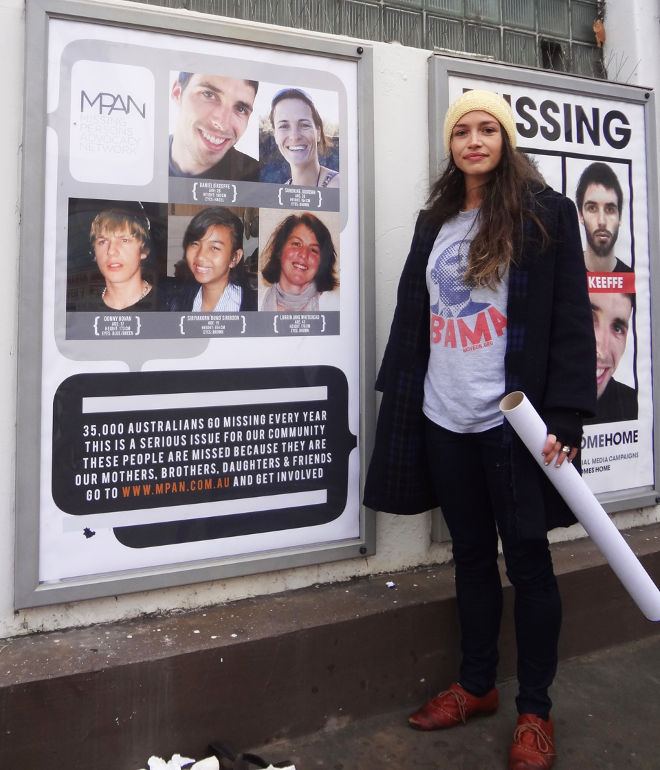

So she decided to formalise the advice she was constantly sharing with others. She won her first charitable grant and, in 2013, started the Missing Persons Advocacy Network, MPAN for short. With the help of volunteers Loren produced the Missing Persons Guide , a practical guide for what to so when someone goes missing.

After a lot of searching, Loren found plenty of support groups, but nothing that offered practical help to friends and family of missing people. Practical support is important for two reasons: when someone is missing, you feel useless and helpless. Having a practical action to take helps both in terms of getting coverage for the missing person and for feeling engaged.

While there are government agencies like the National Missing Persons Coordination Centre that run initiatives during campaigns like National Missing Persons Week, and list the details of the missing, Loren says MPAN is different: “MPAN aims to support families of all missing persons, at all times of year, and work with them directly so that our initiatives humanise their loved one rather than just list their physical descriptors,” she says.

–

Have You Seen This Charity?

Although missing persons are the focus of MPAN, many other fledgling not-for-profit organisations are in similar positions; struggling to get a foothold in a crowded charity sector, with no formal support or training. It’s easy enough to start a new charity; most people in the sector are running off passion and commitment and learning the rest as they go along. But many new organisations fail to thrive when the enthusiasm wears off and the dollars are not forthcoming.

Loren admits that applying for grants and fundraising has been the hardest part about starting MPAN. Missing persons doesn’t slot nicely into the categories often specified by funding bodies, and public fundraising is hard because as Loren explains, “most people don’t see it as a charitable cause; it’s an area mostly associated with the police and Crime Stoppers, and that association can make it very difficult for people to empathise.”

MPAN’s biggest challenge is to break the stereotypes and shake the taboos surrounding missing persons. Loren hopes that by doing this, the funding will follow. But she admits that at times it can be difficult: “Trying to maintain the momentum when MPAN’s interactions [with those needing help] are often intense, short-lived and regularly have devastating outcomes… it’s hard”. Often when a missing person is located, it’s not a happy ending.

MPAN has worked around the lack of funding in creative ways. The ‘100 A DAY’ campaign leverages unsold advertising space in print media, whilst ‘Help Find Me’ calls on owners of blogs and websites to donate search bar and banner space.

While this is a great way to soldier forward, Loren says she has higher-reaching plans: “In five years’ time, I’d love for MPAN to have reached a point of financial sustainability”. Right now MPAN is an organisation mostly run by volunteers, but Loren has high hopes for what could be done with just a few paid staff and formalised partnerships with key stakeholders. Loren has spent time with Missing People UK, which has been built over decades and now has a 24-hour help line. She hopes that in the age of technology, the growth of MPAN can be even faster.

–

Ambiguous Grief: Life With A Missing Loved One

Aside from searching, there are so many practical and emotional questions for the loved ones of missing people that probably don’t cross the mind of the average person. How do you stop the electoral commission sending fines for missing people who haven’t voted? What do you do about paying their rent or mortgage or car registration or health fund memberships?

Loren recently made headlines again when she tried to get the Melbourne Cricket Club to put Dan’s membership on hold. MCC memberships are like gold; Dan had been on a waiting list since birth, and since Dan went missing, his family have been paying hundreds of dollars a year to keep the membership current. While they want to maintain his membership for practical and emotional reasons, unfortunately, organisations like the MCC don’t have any contingencies in their club rules to deal with these situations.

While it might seem like a small thing from the outside, it’s just one more example in the list of daily challenges and blows to the families of the missing. Loren hopes that by publicly fighting these battles for her family, she can help make it easier for the next family in the same situation. Loren is now working with the MCC to find a suitable outcome.

Those left behind are dealing with ambiguous loss – a state of grief for which there is no real resolution. “The physical and mental impact is huge and relentless,” says Loren. “Thousands of Australians are dealing with this every single day – we just need to know if our favourite person is okay. Can you imagine?”

–

Emma Beckett is a scientist by day, but in her spare time volunteers for the Missing Persons Advocacy Network (MPAN), because she wants it to exist if someone she knows ever goes missing! Emma is the admin for MPAN’s twitter account (@mpan_au).