Growing Up Gay In Indigenous Australia

"When I came out to my father, he told me he used to bash people like me." A syndication from Archer Magazine.

Junkee is publishing a series of in-depth pieces on gender, sexuality and identity in conjunction with Archer Magazine, the Australian journal of sexual diversity. This article was originally published in Archer #2, June 2014. Subscribe to Archer here, and Like them on Facebook here.

–

The Big Bang Theory tells us that after the start of the universe, there was an amorphous cloud of atoms and particles. The catalyst for the coalescing of the gases and dust were very small differences in that early cosmic soup. If it wasn’t for these differences and mutations, the universe would never have formed.

I find enormous comfort in this: that nature thrives on difference.

When you’re Aboriginal, you’re always reminded of your difference – from the sideways glance of a shop assistant to the excitable look of school children when you’re delivering a Welcome to Country. When you’re Aboriginal and gay, there are layers of difference and this can be challenging for some people.

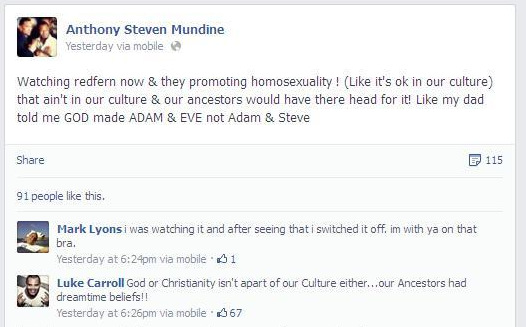

Since the emergence of the marriage equality debate, there have been a number of squeaky conservative cogs that provide fodder for the media, and see eye to eye with the coalition government. These voices shudder at the thought of anything that challenges their notion of ‘normal’. I’m thinking of the opinions of folks such as Anthony Mundine, whose anti-homosexuality views were widespread following a Facebook outburst late last year.

Not only is anti-homosexual rhetoric cruel and demeaning, it is also increasingly out of step with mainstream Australia. In the case of Mundine, it was also out of step with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (ATSI) leaders and thinkers, as well as the wider community.

Of course, diversity of thought exists in the ATSI community. And to that end, many indigenous LGBTI people experience homophobia and transphobia in their own lives. Unfortunately, the perpetrators are often their own people or family.

I was about five years old, I reckon. My father, a Wiradjuri man, and I were getting out of our old family Valiant. We lived in what was called ‘the new mission’, in Macauley Street in Deniliquin, New South Wales. All the blacks had been moved to Deniliquin from Moonacullah Mission some 20 years earlier.

The charming houses built for the Moonacullah Aborigines were fibro and erected on the fringes of town, not far from the sewerage plant. A stiff northerly breeze carried the smell of raw faeces into our street, and if there was an operational issue with the works, the town’s sludge would come bubbling up into our bathrooms. Not exactly a welcoming experience of assimilation.

Deniliquin was, and still is, a pretty town on the Edward River (Koletch, in our Wamba Wamba language). Ever since I can remember, the sign coming into town announced that there were 8000 people living there.

On this particular summer day, after my father had been looking after me (I sit in the corner of the local TAB while he bets on the horses), we arrived back in Macauley Street to discover he’d left the house keys inside. He ordered me to climb through the window to open the door, but I refused. His response was to verbally abuse me and, for the first time in my life, I was called a ‘poofter’. I didn’t know what this word meant, but, considering the tone of its delivery, I knew it couldn’t be a good thing.

Over the following years I heard this word a lot more, and figured out its meaning. Given my pre-pubescent romance with another boy, I soon knew I was this thing.

This was the prism through which I saw my early sexuality. In the community I lived in, I did get a sense that homosexuality was not a good thing within our mobs. And, of course, like all homophobia and all bigotry, these attitudes were designed to de-humanise me, to marginalise me and to keep me down.

The host of these parties was known as Aunty Sharon, a redhead with striking features and a beak-like nose, who spoke beautifully and loved hugging us kids. She was my mother’s boss and she lived in Waterview Street, Balmain, with her girlfriend.In 1978 my mother wisely left my father and moved to Sydney with my sister and me. Mum moved in some pretty funky and arty circles and we were often at bohemian parties in Balmain. My sister and I would hide under my mother’s skirt while mysterious white people drank and danced and ate exotic food.

My mother never had to explain any of this to me and I lapped up the experience, as any curious child would. I loved our visits to Aunty Sharon, and the look and smell of her house. My favourite thing was to fall asleep cuddling her life-sized Wonder Woman cushion.

In hindsight, these were formative years that helped to empower my sexual identity and sense of self-worth. My mother never sheltered us from these influences. She knew I was gay all my life, I suspect, and when I finally came out to her in 1991, she said “surprise, surprise”.

My mother is a proud Wamba Wamba and Muthi Muthi woman and she knows her culture, her ancestors and the way forward for her people. She spent her life working for the mob and instilling her knowledge into future generations through environmental work, weaving and storytelling.

My father, on the other hand, is highly colonised and, in my opinion, a tragic figure of a man who was never there for any of his children. When I came out to my father, he told me he used to bash people like me. Whenever we fought, homophobic insults were not off limits.

I have seen this prejudice in other families in Deniliquin, too – we must have been a queer little community, given how many gay and lesbian relatives I have. One experience that springs to mind is that of my cousin Henry, who is transgender. Henry blossomed into Violet during her teen years. Not knowing how to deal with this change, her brothers were brutal and violent.

Violet moved to Newcastle and rarely returned home. Despite all this, there remained a staunch set of sisters, nieces, nephews and cousins who adored her, kept in regular contact and resisted, berated and belittled those small-minded brothers.

This group also provided powerful protection for the rest of us LGBTI kids growing up. Hopefully, the prejudice of the old uncles dies with them.

We were also lucky enough to have Elder LGBTI people guide us through our childhood and coming-out phases. Small country towns are not the most hospitable places for young black kids, let alone young black LGBTI kids.

That said, homophobia still finds fertile ground in our communities. In late 2013, a boxer by the name of Anthony Mundine unleashed a homophobic rant on Facebook following an episode of Redfern Now. Mundine’s comments released a flood of memories for black LGBTI people like me, and gave room for more indigenous people to express their homophobic beliefs.

If anything good came from Mundine’s incendiary comments, it was the chance for collective self-reflection for Aboriginal LGBTI people, along with their families and supporters. For every person who supported Mundine there were dozens who spoke out against his narrow-mindedness, promoting the loving acceptance of gays and lesbians in our community. And it has also encouraged support and advocacy for black LGBTI peoples in local and broader representations.

The contrast between my mother’s open-hearted embrace of my sexuality and my father’s hateful reaction made me contemplate the idea raised by Mundine about the place of homosexuality in so-called ‘traditional’ Aboriginal culture. There are indications from some cultures around the world that diverse sexuality is an integral part of ‘traditional’ indigenous life – for example, the Sistergirls of the Tiwi Islands, or the Two-Spirit movement found among some Native American cultures.

There is also a logical and reasonable approach to this argument: Aboriginal people have been in Australia for more than 60,000 years in what many anthropologists describe as a triumph of survival and mathematics. Given the overwhelming evidence that homosexuality is biological, it is logical to assume that homosexuality would have been a part of such a social equation. It is estimated that there have been four billion Aboriginal people In Australia since the dawn of time. Four billion, and not one gay person? That just defies belief.

Some argue that our culture would have oppressed such behaviour. This raises some interesting questions, as well as some colonial mythologies. Which traditional Aboriginal culture is being referred to here? When white people colonised Australia, there were hundreds of Aboriginal cultures. To know the mores and values of every single Aboriginal culture would be a major feat of anthropological prowess – one of which I doubt Mundine and his ilk are capable.

This argument also ignores the major diversity between groups, and indeed within them. This is why a homogenous approach to government policy doesn’t work, and why a consensus on constitutional reform will probably never work. We are as diverse as any other ethnicity and this must be acknowledged to really move forward.

This idea of ‘traditions’ is also dangerous because it glues us to the past, rendering us immovable and static. It also sets up a system of haves and have-nots – those who have maintained their ‘traditional’ culture, and those who have lost it.

All cultures change, and Aboriginal people would not have survived for so long had they not been adaptive and dynamic.

This responsibility would not be given lightly. It is a position that involves trusting a person’s character. The fact that LGBTI people have been entrusted in these processes speaks volumes for the support we have within our communities. As for gay people being accepted in Aboriginal communities, I know a dozen or more black LGBTI people who are strong and powerful leaders in their communities. Some have led their mobs to successful native title consent determinations – a role that is built on trust. A native title case would include holding secret knowledge of sacred sites, family histories and land management practices, not to mention being entrusted to negotiate on behalf of thousands of claimants.

Of course, there will be narrow-minded people in our communities, too. We may dislike the Fred Niles, George Pells or Tony Abbotts of mainstream culture, but we are not surprised that those voices exist in a liberal democracy. There are narrow-minded indigenous people. There are also indigenous fundamentalists, climate-change deniers, racists and misogynists.

When I think of these people, or when I hear their bullshit in the media, I think of my accepting, unsurprised mother. I think of my sisters fighting for my rights, and defending my cousin Violet, and I remember the embrace of that Wonder Woman cushion.

–

This article was originally published in Archer #2, June 2014. Subscribe to Archer here.

–

Steven Lindsay Ross is a proud Wamba Wamba man from Deniliquin, New South Wales. Steven has worked in water management, Indigenous rights, crime prevention and the arts, and has attended two United Nations meetings on Indigenous issues.

–

Feature image by Stelios Papadakis.