Are The Greens Reshaping Themselves As A More Radical Party?

This could be what Australian progressive politics needs right now.

The rise and rise of right-wing populists across much of the developed world, including here in Australia, has sparked an enormous amount of debate on the progressive side of politics around what we’re doing wrong.

“Stop talking about race!”. “Stop talking about gender and sexuality!”. “You’re alienating working class people!”.

Most of the arguments have focused on what the left has been doing wrong, rather than what it should be doing instead.

But recently there have been some signs that the Australian Greens are learning the lessons of massive global political shifts. A number of policy announcements suggest that the party is willing to reposition itself as a bolder, more radical party seeking to tap into voter frustration with the status quo and articulate a different vision for society.

Have The Greens Stopped Trying To Be “Mainstream”?

Recently, I’ve criticised the Australian Greens for seeking to replicate “mainstream”, moderate politics and prioritising parliamentary deal-making as the primary method of securing social change.

Under a strategy pioneered by former leader Bob Brown, the Greens sought to position themselves as a non-radical, palatable alternative to the current major parties. Bit by bit the party jettisoned policies that drew the ire of conservative tabloid newspapers.

The party watered down its progressive drug policy in the lead up to the 2010 election by inserting a clause that explicitly ruled out the legalisation of any currently illegal drugs. In 2012 a major rehaul of the party’s policy platform saw the Greens abandon their support of an inheritance tax.

While the Greens were attempting to present themselves as moderate political players, the electorate’s antipathy towards politics and politicians continued to build.

Voters flocked to minor parties in the Senate in both 2013 and 2016, sending a clear message to establishment political parties that they were fed up. But the Greens failed to benefit from that growing sense of populist outrage. Their vote fell in the Senate in both elections.

Instead the beneficiaries were the short-lived Palmer United Party (though Jacqui Lambie has stuck around), the Nick Xenophon Team and, of course, Pauline Hanson’s One Nation Party. Voters were clearly looking for alternatives that rejected the political status quo, and it seems as though the Greens relative longevity (at least as far as minor parties go) and their attempts to moderate their policy position, failed to capture the imagination.

But over the last few days, early signs have emerged that the Greens are seriously considering their policy platform and are willing to re-embrace the same ideas that were dumped for being “too radical” only a few years ago. The party has shifted its position closer towards drug legalisation, hinted at support for an inheritance tax and articulated a bold new policy when it comes to the rights of workers.

These policies, and the political shift they represent, could help provide a blueprint for the future of progressive politics in Australia that recognises voters are sick of politics as usual.

The Greens Are Right To Restart The Drug Debate

Over the weekend the party ditched its opposition to the decriminalisation of drugs and launched a new policy that acknowledges the war on drugs has “failed”. Under the policy, recreational drugs like cannabis could be legalised while other drugs, like heroin and ice, would be treated as a health (rather than law and order) issue.

The policy echoes the calls of leading medical experts who are asking that politicians to move beyond outdated criminal justice approaches to drug policy. The Greens are also talking cues from Portugal, which decriminalised all drugs in 2001 and has seen a reduction in use and harm ever since.

The party has already been attacked by the usual suspects in the conservative media for its new policy. But it’s absolutely the right move. It is supported by the evidence and it’s a much-needed intervention in Australia’s stilted and virtually non-existent political debate around drug law reform.

The role of progressive political parties like the Greens should be, in part, helping to shift the boundaries of social debates. Instead of accepting the terms of engagement set by institutions like The Daily Telegraph (as the last policy did, for example), they should try and re-write them. That’s what a policy like this does.

It isn’t the most radical proposal in the world, but it re-frames the argument. Rather than accepting politics as it is and trying to find a place where the Greens can fit in, a policy like this is about smashing politics wide open and putting forward new ideas for more caring society.

We Need More Progressive Economic Policies

There’s been a lot of analysis around the fact that Donald Trump successfully tapped into the concerns of working-class communities in declining industrial centres, anxious about their employment and the future economy.

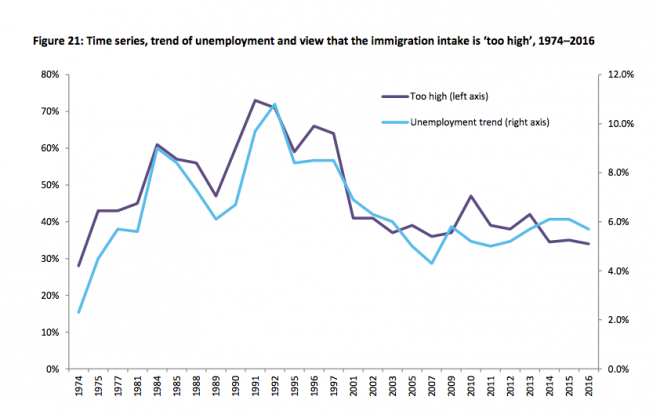

The same has been said of Pauline Hanson’s resurgence here in Australia. The fact is, there is a correlation between the precarious nature of the economy and concerns around immigration.

This graph shows how concern around immigration levels closely tracks the unemployment rate.

Scanlon Foundation Mapping Social Cohesion 2016 Report

Trump and Hanson-esque rhetoric on race and migration has been given a great deal of credence because of this. We saw that recently with Bill Shorten’s lazy attacks on foreign workers. Rather than addressing the root causes of income inequality and a slowing economy that can foster these kinds of sentiments, politicians on the right and the left choose to focus on the symptoms instead, jumping on the anti-immigrant pile-on.

In the last week, the Greens have put forward two progressive economic policies that are about seriously addressing inequality. Like their new position on drugs, they will be attacked by conservatives and probably by the Labor Party as well.

But in an era where voters are sceptical of an economic agenda that delivers for the wealthiest and leaves everyone else behind, they could find strong support in the community.

The first is an inheritance tax. After the party abandoned the policy in 2012, Greens leader Richard Di Natale has recently flagged support for the idea.

The ABC’s Michael Janda has pointed out that inheritance taxes are quite common in the developed world. Most OECD countries, including the UK and the US, have them in some form and their an efficient way of re-distributing wealth.

With an appropriate threshold, you can imagine a populist campaign targeting the likes of Gina Rinehart and James Packer, arguing that a portion of their obscene wealth could be used to fund investment in health, education and infrastructure rather than all being handed down to their children.

Di Natale’s proposed tax is very limited and would only apply to investment properties, but now is the right time for progressives to start debating policies designed to redistribute wealth and build a fairer Australia.

The Greens have also put forward a new policy to protect low-paid workers from being exploited by large companies. It’s a response to recent scandals involving the country’s largest union, the Shop, Distributive & Allied Employees Association (SDA), that have seen some workers in the rail and fast food sector see their pay drop as a result of union negotiated deals.

The idea isn’t radical, but thanks to the narrow scope of the debate around industrial relations in Australia, it will be attacked by big business and the Coalition as unreasonable. The Greens only have one member in the House of Representatives, so it’s unlikely to become law. But, like the inheritance tax, it’s an example of how a minor party on the left can help drive the debate around a fairer economy.

We Need More Radical New Ideas

It should be obvious that a new drug policy and an inheritance tax aren’t a kind of magic bullet to fighting off the rise of Pauline Hanson. Both are good policies, in their own ways, that would make Australian society a better and fairer place if they were implemented.

But they are important because they reflect a significant strategic shift within the Greens. They indicate that the party is recognising that “mainstream” moderate path it pursued in recent years is leading to hollow ground.

I am not seeking to portray the Greens as the great heroes of a progressive Australia. They are far from perfect. I think it’s supremely disappointing, for example, that a party that seeks to portray itself as a left-wing opposition to One Nation has a federal party room that consists entirely of white people.

But when it comes to policy, these recent announcements are a positive step.

The public is rightly cynical of the political consensus that has dominated Canberra. The economy is stagnating, community divisions are bigger than ever but politicians are still prioritising the interests of the wealthy elite.

By acknowledging their mistakes, as the Greens have done, and developing bold new policy initiatives, progressives can harness that sense that frustration and channel it to help build a better society, rather than letting the likes of Pauline Hanson exploit it for their own divisive purposes.

Osman Faruqi is Junkee’s News/Politics Editor. He is also a former office-bearer of the Australian Greens and has previously worked for Greens MPs.

–

Feature image via Senator Richard Di Natale/Facebook.