Grant Morrison On Misfits, Mutants, And Comics As Revolution

We nerded out with the Scottish comics legend ahead of his appearance at Sydney's Graphic festival this weekend.

Grant Morrison is a writer, occultist, and counter-cultural anarchist of comic books. A native of Glasgow, Morrison — alongside fellow authors Alan Moore and Neil Gaiman — was one of the leading members of the late ’80s ‘Brit Invasion’ of American comics that completely revitalised the then struggling industry, making comics smarter, darker and a whole lot more interesting.

He’s perhaps best known for his iconic runs on Animal Man, Doom Patrol and his creator-owned series The Invisibles, but he’s also gone on to be a main writer on some of the biggest franchises in comics such as X-Men, Batman, Superman, JLA (Justice League of America), and the DC universe-wide crossover, Final Crisis. Even if you’ve never picked up a Morrison comic, you’ve doubtlessly come across his legacy: the ultra successful Arkham Asylum video game franchise is partly based on Morrison’s defining 1989 graphic novel of the same name, and his 1994 series The Invisibles is largely speculated to be the basis for The Matrix.

During a 15-minute chat ahead of his appearance at Sydney’s Graphic festival this weekend, we discussed everything from his work to fetish clubs to Superman punching dinosaurs.

–

Junkee: You’re travelling to Sydney for a one-on-one panel with Gerard Way (creator of the comic book series Umbrella Academy, and former lead singer of My Chemical Romance). What can we expect?

Grant Morrison: It’s going to be a lot of new stuff and new ideas. I’ve been writing a little piece I hope to read, and there are going to be a few surprises. I’ve been tied down to DC for the past decade, writing a few comics a month, so it’s only now that my schedule is freeing up that I can branch off. I’m working on a screenplay for an animated movie, a few TV projects, as well as making some new creator-owned content.

Gerard and yourself both focus on misfit characters, which we can especially see in your titles Animal Man, Doom Patrol and The Invisibles. What keeps drawing you back?

I guess it’s cause most of us feel that way. I particularly felt that way when I was young — just a little twerp kid with mad ideas and weird friends — so I kind of always identified with outsiders. I think unless you’re one of the ruling class of a country, unless you’re Prince William or Harry, you’re gonna feel like an outsider. If you’re them, you probably feel it even more. So honestly, it’s purely a functional reason. These are the people I grew up with and the people I felt.

New X-Men #135. The boy in the gimp suit’s mutation is that he permanently turns into sentient gas. The others aren’t much better. [art by Frank Quitely; Marvel, 2003]

I remember when you moved onto the X-Men, the freaks of Marvel’s universe, you created your own X-Men ‘Special Class’ made of mutants who were kind of shitty, outsiders of the outsiders.

Yeah, I always felt there just wasn’t enough attention given to mutants who weren’t beautiful. You know, ’cause [former X-Men authors] Chris Claremont and John Byrne always drew and portrayed beautiful people. You know, skinny little Kitty Pryde… Well, she was a good-looking girl. I just always thought there have to be mutants who look like real fucking mutants, and I felt like we needed to hear from those people as well, the ones who didn’t just look like fashion models, didn’t come from an Abercrombie & Fitch ad.

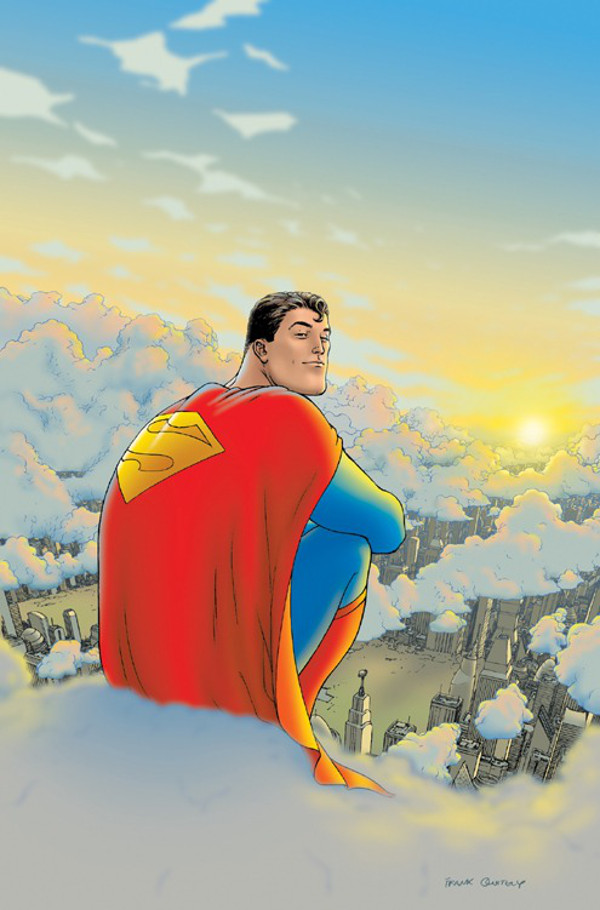

That run was pretty dark, with most of Special Class dying while the other mutants got addicted to the drug ‘Kick’. You’re known for doing some pretty fucked-up shit: The Invisibles featured fetish clubs, voodoo gods, the Marquis De Sade, rapes, serial killers and lobotomies. But you go from that to something like All-Star Superman in 2008, the title that people now call the quintessential Superman book. When I read it, I get this overwhelming sense of love. How did you make that transition?

Well, that one was more because the character you’re dealing with has to make you feel that way, don’t you agree? Batman makes you feel a certain way: he’s all angsty and cranky and it’s about the night and the dark thoughts you have and trying to conquer them. With Superman, he represents the very best in humanity and in a way represents the best we can aspire to. I think when you’re telling a story with that guy, you’ve got to go to his place and imagine how good he would be.

And I had to make that reflective in the story structure, too. My style is normally quite improvised and chaotic — there’s a lot of structure in there, but at the same time I like to keep it open. But with Superman, I was trying to do something very ordered and rational, kind of based on Leonardo DaVinci and the ideas of the Renaissance and the Enlightenment about how man could be perfected and how evolution could lead us into the sun.

So because the book was called All-Star Superman, I knew it had to be about a star, about a solar theme, so then we had all these ideas about a sun god and Hercules. The structure of the story then rose from the character, and that’s why it feels like Superman. The whole thing was to make you feel the way that Superman feels — you know, this very bright, positive, humanitarian outlook.

All-Star Superman [art by Frank Quitely; DC Comics, 2008]

Switching to the darkness, you just finished a seven-year run writing Batman. You had Batman travelling through time, having a son, the former Robin fighting to wear his cowl, and eventually Bruce establishing a multinational group of ‘batmen’. There’s this recurring idea that Batman can’t be stopped, he’s eternal. I have one page in particular burned in my mind: Batman, back in the Neolithic era, painting the bat sigil on a cave wall. What was this all about?

Batman is a figure of darkness and, you know, just to be clear, I’m not trying to do realistic versions of these characters because I don’t believe stuff like this could ever exist in the real world. So I’m not trying to do Christopher Nolan with Batman, ’cause he’s sitting there working out, like, how would it work and what tools would he need. For me, Batman is a symbol, so that makes me do stories where I can play with that and explore what it means to have Batman inside people’s heads.

What I’ve learned is that he’s that one guy in a trial who stands up against the darkness and the thing that everyone’s scared of. All through history that character recurs, and right now in the 21st century, Batman is the best expression of that. I guess it’s why my Batman is deliberately non-realistic, even though obviously within the stories he can still be hurt, bruised, starved or betrayed. He couldn’t ever exist in the real world, so to me the idea of telling stories where he’s realistic is kind of daft.

Final Crisis #7 [art by Doug Mahnke; DC Comics, 2008]

So what do you think then of the realistic tone set in Nolan’s films continuing into Man Of Steel and most likely an upcoming Justice League film? Do you think that realism is maybe needed for moviegoers rather than comic readers?

I’m sure that moviegoers enjoy anything and tend to enjoy whatever they’ve paid money for, so that’s fine. You know, I’m sure they’ll be done well and Man Of Steel was done well. Just to me, the idea of making them realistic misses out on all the possibilities of treating them as purely symbolic aspirational figures. And look, I’d just rather see Superman fighting dinosaurs or flying through time rather than trying to tie him into the military industrial complex or talk about 9/11 or all these slightly tired ideas. It’s a difference in tone and approach.

I think the wider public would just as eagerly respond to a really colourful and imaginative Justice League movie, as to a dark or dystopian or, you know, otherwise realistically-inflected version. But honestly, in a character like The Flash, there’s no realism in these concepts at all, but what they have is an emotional depth and a weight and a symbolic value that’s just so much more interesting to explore.

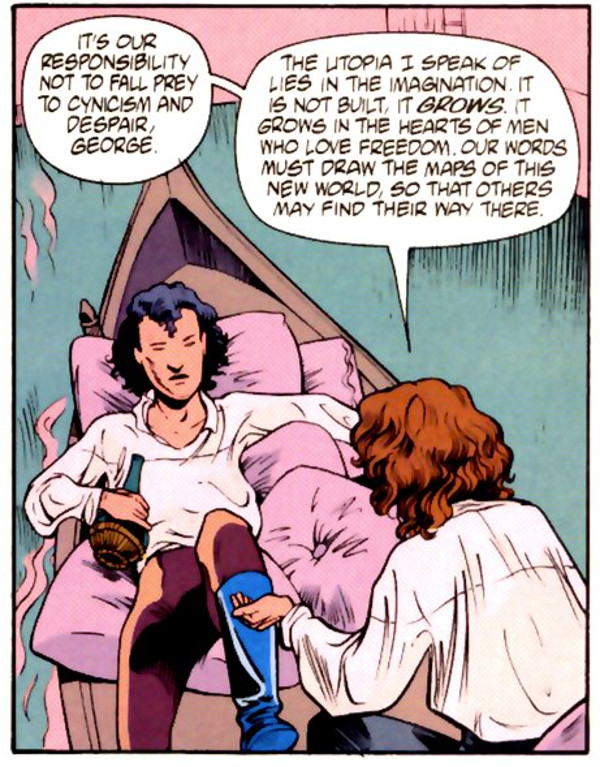

The Invisibles #5. Lord Byron in Venice, drinking wine and chilling with Percy Shelley. [art by Jill Thompson; DC Comics, 1995]

You used to be known as the punk of comics. The Invisibles fought any and every authority, and everything was so heavily philosophical — you know, you featured the Romantic poets, transcendentalism, Gnosticism, chaos magic, Dadaism, and in one issue a character summoned the spirit of John Lennon. Now that you’re dealing with the big guns of DC, all that stuff has maybe become less apparent. Are you still leading a revolution?

Yes definitely, the same impulse is in all of this stuff. I’ve just been thinking about it today and reading some William Blake, where a lot of these ideas of fighting ‘mind-forg’d manacles’ kind of come from. It was the same with the other Romantic poets like Shelley and Byron; I used to write them directly into my comics or have my characters quote them, and I think that was me just trying to absorb it all. But now — and I think you can see it in my work — I just get it. It’s just all more natural. I’m not saying I’m as good as any of these great poets, but certainly that same radical impulse is in all my work. You know, I think superheroes are our possibility of what man could become, a realisation of our own inner superhoods, so whether I’m writing Superman or punks, it’s still a revolution.

–

Head to GRAPHIC 2013 at the Sydney Opera House this weekend to see Grant Morrison in conversation with Gerard Way on Saturday October 5, and on a panel with Lein Wein and Dave McKean on Sunday October 6.

–

Paul Dalla Rosa sub-edits fiction for Farrago Magazine, co-hosts ‘The New Pollution’ podcast, and reads too many comics. Find him on twitter @PaulDallaRosa

[lead illustration by Frank Quitely, via Bleeding Cool]