Is TV Finally Ditching The ‘Gay Best Friend’?

"The 'gay best friend' trope is homosexuality on straight people’s terms. We deserve better."

Gays! They’re everywhere these days: in our homes, in our clubs, in our politics, and flocking together like tropical birds on our reality TV shows.

In terms of TV representation, we’re doing better than before. We’ve got gay wizards, gay superheroes and gay teenage detectives on our screens. We’ve got trans and gender non-binary characters in several television shows, such as Orange is the New Black and Transparent. But as heartening as it is seeing LGBTQI people on screen, showrunners still have a duty to make sure these characters are more than simple ticks in a box.

We deserve characters that fulfil more function than simply being on-screen and gay. We deserve better than the storied and egregious ‘gay best friend’.

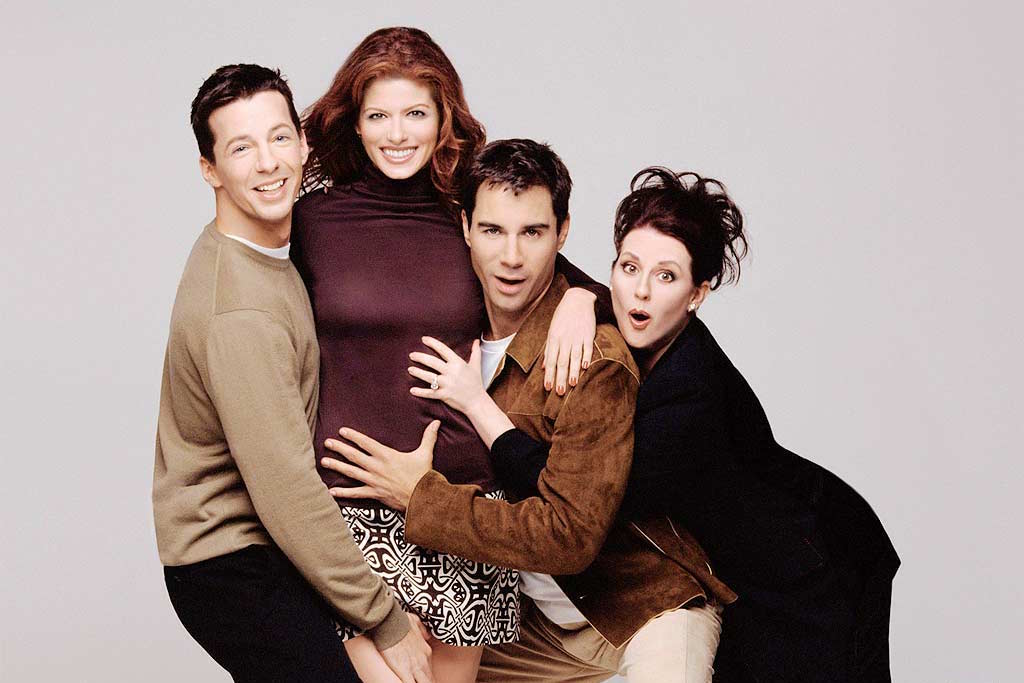

Where There’s A Will (And Grace) There’s A Way

The gay best friend has been a TV staple for decades now. If there’s a woman on TV having romantic issues, you better believe there is a sassy gay stereotype giving her wise yet arch advice. Think Stanford Blatch from Sex and the City, who was defined by an endless hunger for Carrie’s non-stop drama and poor relationship choices. He was the template for the gay best friend — the Platonian ideal.

George from Julia Robert’s best film My Best Friend’s Wedding was another notable member of the GBF (Gay Best Friend) vanguard.

They always seem to be men as well, with the few examples of lesbian best friend managing to fall outside the characteristics of this trope. This is probably because lesbian visibility on television is much lesser than gay men (imagine if Buffy started a trope of lesbian best friends who love to flay men with dark magic).

The gay best friend is ultimately defined by how much of an accessory he is to the straight protagonist. He’s basically only pulled out for special occasions, when someone needs a sympathetic ear, a shopping montage, or perhaps some gossip in a cocktail bar. In Sex and the City’s heyday, the gay best friend became a sign of status for the cultured, inner-city lady — as important as a pair of Manolo Blahniks or a Cosmopolitan.

“It’s homosexuality on straight people’s terms.”

The problem with this trade in stereotypical gay men is that it implicitly defines what an ‘acceptable’ form of homosexuality looks like — and in TV, that’s defined by what’s commercially viable. While the GBF is inherently bound up in notions of sexuality, they are rarely seen as sexual beings. The act of gay sex is still tip-toed around on a lot of television, especially commercial networks that are aimed at ‘families’. In some cases, this can even extend to displays of homosexual affection.

While still being represented, the gay best friend becomes hidden behind an outdated set of actions and behaviours, cloaked by acceptable, non-threatening stereotypes.

A lot of the conservative response to homosexuality is about ‘not forcing it down people’s throats’. Apart from being an overtly sexual terminology, this is exactly the kind of homophobia that the GBF trope often plays into. It’s homosexuality on straight people’s terms, rather than true representation of how gay people live.

When the only gay person on a show is given unequal time for their romance — or their love life is even treated as the comic relief, we’re overtly being told that straight people’s love is not only more important, but also the default. We’re being told that homosexuality is different, the ‘other’. Both Will and Grace were the main characters in their own show, for instance — but as revolutionary as that was at the time — we definitely heard a lot more about Grace’s love life.

Too Gay To Function

This is a trope that has slowly been put out to pasture, but it’s particularly interesting to analyse with a bunch of shows from the golden era of GBF now getting reboots. The short-lived SATC spin-off The Carrie Diaries had its own precursor to Stanford Blatch, Gilmore Girls rebooted with a partner for Michel, and Will and Grace is on its way too.

Although I don’t want to be complacent, it feels like new shows are taking more care in developing new gay characters. The bar has been raised so high with gorgeously three-dimensional gay characters and their complex gay romances in shows like Sense8 or Please Like Me, that it shines a stark contrast on shows that aren’t putting in quite the same effort.

This year, Netflix’s new teen-drama Riverdale features a gay character in the blandly handsome Kevin. Kevin was also gay in the Archie comics from which the show was based, although he was a late addition, only joining the gang in 2010 (which earned the comics a GLAAD award at the time). But I am watching the TV version of him like a hawk.

At present, while the series shows a delightful self-awareness to the gay best friend trope — even referencing the out-of-date cliche by name in a slick burn by syrup heiress Cheryl Blossom — they still have prioritised not only all the straight people romances over his own, but also Archie’s never-ending quest to play ‘Wonderwall’. When a bro’s love of guitar is prioritised over the one queer romance in a show, I get suspicious.

Everyone’s problematic fave, Girls, has also ignited discussion of the trope. Though he’s been the subject of criticism in the past, Hannah’s best friend Elijah was given a great deal of development in the show’s final seasons.

While he was always a go-to for support, bitchy gossip, and coke-fuelled nights out, he was also given space to grow through a complicated and full relationship (with full on-screen sex) as well as a standalone episode that focussed on a potential career path. Elijah might not be the main focus of the show — not being one of the titular Girls — but he is absolutely characterised as a full and real person with issues and arcs, who lives outside of Hannah’s problems.

Narratively, it’s worth having this diversity of romances — by limiting the GBF to a staid supporting role, we’re limiting the scope of our own stories. We’re limiting the worth of our representation on screen, forcing queer people into unrealistic moulds. And we’re limiting how many hot men we get to see kissing, and that I won’t stand for.

–

Patrick Lenton is a writer and author. He tweets at @patricklenton.