Forgot About Dre? With ‘Compton’, The Granddaddy Of Gangster Rap Just Made His Masterpiece

Dre's first album in sixteen years is a harrowing, melancholy work of genius.

As of last month, Dr. Dre was the most influential, culturally significant and wealthiest living musician not to have dropped an album in Willow Smith’s lifetime.

His confusingly titled 1999 release, 2001, hit record stores (record stores!) before Survivor, Dora the Explorer and CSI had even aired their first episodes. He kept promising to someday loose the fabled follow-up Detox, but besides a few abysmal leaked tracks, it just never eventuated.

Then, in August of 2015, he unveiled Compton: A Soundtrack by Dr. Dre, a surprise companion piece to Straight Outta Compton, the NWA biopic he co-produced. (The film arrives in Australian cinemas this week.)

It had taken 5744 days for Dre to make good on his promise. For context, Guns n Roses’ notoriously late Chinese Democracy took a comparatively swift 5479 days to manifest. You could squeeze the entire production of Boyhood in-between Dre’s LPs.

To quote Stain’d, “it’s been awhile.” So, let’s look back on why, exactly, Dr. Dre matters, and how Compton is unexpectedly one of the year’s most relevant releases.

–

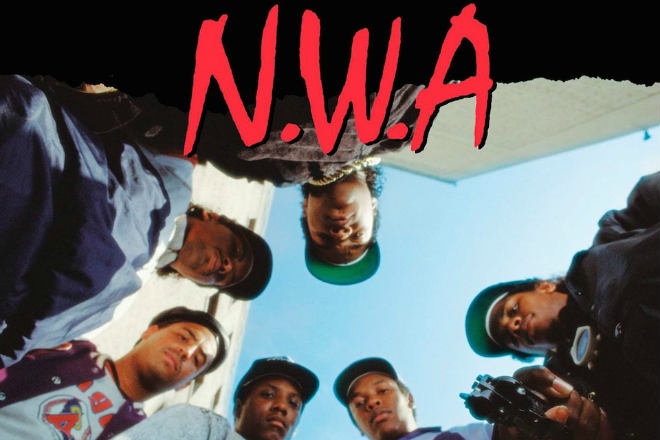

NWA And Straight Outta Compton Revisited

Andre Young – aka Dr. Dre — first made a name for himself as a member of ‘80s hip-hop collective NWA, alongside Ice Cube, Eazy-E, DJ Yella, MC Ren and Arabian Prince. The making of their first album, Straight Outta Compton, is what’s documented in the movie that shares its name, along with a depiction of the social schism caused by its hit single ‘Fuck Tha Police’; an anti-authoritarian anthem for persecuted black Americans that anticipated the LA Riots of 1992.

NWA burnt out quickly, but Dre recovered by forging Death Row Records with Suge Knight and releasing The Chronic, a funkified outlet for his music geekery and production prowess. Few artists can boast about creating a sound. Dre can.

And yet, he’s probably best known these days as the co-founder of Beats by Dr. Dre, a headphones brand he’d eventually sell to Apple for $3 billion. (It makes sense that he’d also spearhead Beats 1 Radio on Apple Music and even host a weekly program; he’s always seemed to be more interested in curation than rapping anyway.)

With a net worth of $700 million, Dre’s richer than pretty much any (not-McCartney) muso alive. And the one per cent isn’t really known for crafting incisive street poetry, unless Gina Rinehart comes out with an amazing Iggy Azalea diss track sometime soon.

Therefore, it’s understandable many have approached Compton — which was exclusive to Apple before becoming available for quaint, olde-timey physical purchase last week — with cynicism.

Fans had been so patient. Would he really betray them – and himself, given his reputation as a prickly perfectionist – by simply pooping out a synergized cash-in, like this thing?

Dre’s mogul status is such now that it’s hard to consider any of his decisions as anything but purely business-minded. This extends to his belated apology towards his past female victims of abuse, conveniently delivered as Straight Outta Compton began breaking box office records in the States and courting awards season attention.

It’s not the first time he’s expressed regret over his history of violence towards women, so perhaps his ‘sorry’ was genuine. It’s up to his victims to accept it or not, and they can’t be judged for going with the latter. The rest of us, as with any musician or actor with a checkered past, has to interpret their work through the awfulness. “Separating the art from the artists” is how cowards forgive themselves for liking the produce of flawed, troubled or downright bad people. Engage, don’t ignore.

That brings us to why his new album, despite those obstacles, is actually brilliant.

–

City Of Compton, And Why Dre Can Never Leave

Compton is a vibrant, nostalgia-tinged and guilt-filled hip-hop album by a 50-year-old man. We have entered the era in which there can be rappers with multi-decade legacies. There have long been grandfathers and grandmothers of rock, pop and folk. Dr. Dre is a granddaddy of modern gangster rap. On Compton, he reflects on how much has changed, personally and professionally, as well as, devastatingly, how much hasn’t, culturally and socially, for his country at large.

The album’s early highlight, ‘It’s All On Me,’ sees Dre recall over an old gospel track his halcyon days in NWA, and the memories – dark and light – are so potent, it inspires a more emotional, euphoric release than even the movie of Straight Outta Compton can manage. (The film is an entertaining document of an era, but undeniably varnished, unlike the album that inspired it, and the one inspired by it.)

Album closer ‘Talking to My Diary’ sees Dre get lost in a reverie thinking about the late Eazy, regretful over their feud. (Eazy’s unexpected cameo “from the otherside” on ‘Gone’ sends chills up the spine.)

However, what makes the album– and, to a degree, the film – important is its frustrated, no-nonsense portrayal of the epidemic of violence against black men in America. Dre, from his ivory tower, only feels guilt for those left behind. You listen to the album – polished in sound, not in subject – and it’s alarming how much pleasure he’s not getting from his many riches. Compton is an album about survivor’s remorse; on it, he regularly cedes the floor to more modern voices, who illustrate what’s actually transpiring at street level.

Kendrick Lamar (who shared a similarly impassioned album, To Pimp A Butterfly, this year) and relative unknown Anderson .Paak take centre stage on gory mission statements ‘Genocide’, ‘Deep Water’, ‘Issues’, ‘All In A Day’s Work’ and ‘Animals’. (Dre’s pal and the genre’s stickiest barnacle, Snoop Dogg, even takes on the violence in ‘One Shot, One Kill’.)

They’re all bracing listens. Anderson’s raspy, near-tears delivery of the “Animals” hook – “Please don’t come around these parts and tell me that we all a bunch of animals; the only time they wanna turn the cameras on is when we’re fuckin’ shit up” – is about the most heartbreaking sonic distillation of the #BlackLivesMatter movement I’ve heard. For those of us on the other side of the world (and spectrum of experience), it’s essential listening. Compton is an immersive experience. It’s an empathy generator.

Straight Outta Compton director F. Gary Gray was wrong to keep Dre’s violence towards women out of the movie, but not just because it sought to excuse him of his horrific actions. The tales that Dr. Dre and his contemporaries have been spinning for decades now are about systemic injustice – and how leaving a place like Compton isn’t actually ever possible. Compton, or East Chicago, or Ferguson, follows young black men wherever they go. The violence of those stories – and Dre’s past – is tied inextricably to America’s social strata. That’s not an excuse. That’s cause and effect.

That’s why ‘Issues’ – Dre’s supposed retirement track – closes with this defeated refrain: “In the city of Compton, this is where I leave you.” There is no happy ending here. Dre has realised that his message on Straight Outta Compton was an impossible one. There’s no “outta” Compton, no matter how far away one gets.

–

Simon Miraudo is an AFCA award-winning writer and film critic for Student Edge, RTRFM and ABC Radio. He tweets @simonmiraudo.

–

Straight Outta Compton is in cinemas on Thursday, September 3. Compton: A Soundtrack by Dr. Dre is out now.