Film And TV Are Still Boys’ Clubs, And It Needs To Stop

The more things change, the more they stay the same.

“Is most of commercial narrative filmmaking the product of mostly white men? Sadly, the answer is yes.” — director Alexander Payne (Sideways, The Descendants, Nebraska)

When I was at film school, the gender split in our class was pretty even, providing me with an unrealistic ideal of what the industry would be like. While I know and admire several brilliant female filmmakers, we are working (or trying to work) in a field dominated by men — both behind and in front of the camera.

Once you notice it, you start seeing it everywhere. I recently watched Wes Anderson’s new film The Grand Budapest Hotel and I left not caring if it was any good, but pissed off that another film by a filmmaker I admire was so shamelessly full of men. And as for behind the camera: in 86 years, only one woman — Kathryn Bigelow — has won the Oscar for Best Achievement in Directing. For The Hurt Locker. A film about men and bombs. The takeaway message seems to be that if you want to be taken seriously, you need to man up, ladies.

–

Write What You Know?

In a recent piece titled ‘Wes Anderson Answers: Will He Ever Have A Female Protagonist?’, Colleen Barrett argues that “just as female writers and directors… create films with fascinating female protagonists, Anderson defaults to compelling male ones, because it’s what he knows. So, as we lament the film industry being one giant gentleman’s agreement, it’s important not to play the blame game. Because if other male filmmakers are like Anderson, then they’re not trying to exclude women; they’re trying to make the best movies they can.”

Writing male characters because that’s ‘what you know’ implies there is a gaping, elusive, mysterious difference between the genders. Sure, there are idiosyncrasies, but there is no great ‘feminine mystique’. Just like a man, I eat, shit, sleep, love, have sex, worry about work, and what I want to do with my life. Sure, I don’t know what it’s like to be kicked in the balls, but I do know the pain of monthly PMS, and hopefully some day I’ll experience the joy of birthing a watermelon through a hole the size of a walnut. We are all feeling the pain. Barrett’s justification reinforces a divide, rather than breaking down outdated concepts of what it means to be a man or a woman.

Compare Wes Anderson’s films to those of Noah Baumbach, his frequent collaborator. Although Baumbauch co-wrote The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou and Fantastic Mr Fox with Anderson, his own films are consistently littered with complex, memorable female roles, for both major and minor characters. The multi-faceted, real women that populate his films (think Laura Linney in The Squid And The Whale; Greta Gerwig in last year’s Frances Ha) are more often than not inspired by the women in his life. As Baumbach told Indiewire last year, “I like to bring things and people that mean something to me into my work.” Meanwhile, female characters in Wes Anderson films are a rarity, particularly in leading roles. In The Grand Budapest Hotel, of the 17 leading characters, only three are female: two are love interests and one is a maid. I love Wes Anderson’s offbeat and perfectly symmetrical style, but there’s a wealth of quirky, deadpan Margot Tenenbaums just waiting to be written in.

–

“I Think Of A Woman, And I Take Away Idiocy And Idealism.”

Lars Von Trier told highbrow film magazine Sight & Sound in 2011 that, “Whenever I write a film, I write about myself and I might divide myself into two men and then write some terrible female cliché parts that are idiots or idealists or both. Just before I make the film, I switch the sexes around.” It’s not great that when Lars Von Trier tries to write women they are “idiots or idealists”, but the end results are nevertheless complex and unconventional female characters. This is not a trick that is recent or exclusive to the arthouse. Sigourney Weaver’s character in Alien and Angelina Jolie’s in Salt were originally written for men (as were these other “kickass” roles, too). It didn’t ruin the films or limit their audiences — in fact, quite the opposite, according to a recent study on ‘The Bechdel Test’.

The Bechdel Test is a tool for measuring the gender bias in films based on three criteria: that there are at least two named female characters, they speak to one another at some point, and they discuss something other than a man. A recent study of 1,615 films released between 1990 and 2013 revealed that on average, the films that passed the Bechdel Test had statistically lower budgets and yet made more money at the box office. That wasn’t a typo: films can be made with lower budgets, more female characters, and be more profitable than without.

–

But Women Just Aren’t That Funny!

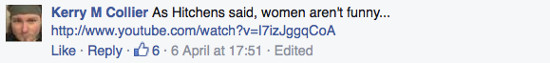

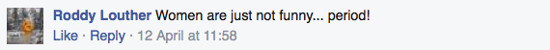

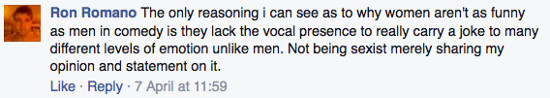

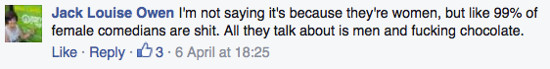

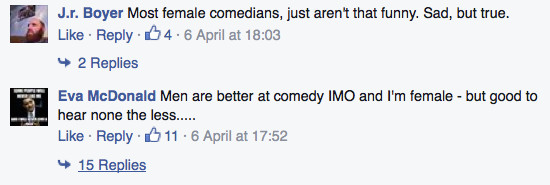

Ricky Gervais recently shared an article on his Facebook in which the author, Rachel Semigran, argued that whilst it’s great Gervais believes in creating “complex female characters” in his comedies, that he needed to put his money where his mouth is, and give us a main female character in one of his shows. What was disturbing — if not unexpected — were the hundreds of comments that appeared underneath his post.

“Women just aren’t that funny…” was something that came up loads of times. Do we really have to start listing names? Okay, let’s, just for fun! Tina Fey, Amy Poehler, Lena Dunham, Sarah Silverman, Kristen Wiig, Melissa McCarthy, Greta Gerwig, Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Mindy Kaling, Aubrey Plaza, Lizzy Caplan, Jane Lynch, Kaitlin Olson, Maya Rudolph, Allison Janney, Carrie Brownstein, Alison Brie, Gillian Jacobs, Yvette Nicole Brown, and so many more. Despite an abundance of talent, this is where we’re at.

–

Some Depressing Stats

A recent report by the Women’s Media Centre (founded by Jane Fonda) substantiates the hunch that women are grossly under-represented in the film and TV industry.

FILM (in the ‘Top 100 films of 2013’)

IN FRONT OF THE CAMERA:

– Females comprised 15% of protagonists, 29% of major characters, 30% of all speaking characters.

BEHIND THE CAMERA:

– In 2013, women accounted for 6% of (US) directors.

– If foreign films in the ‘Top 250 films’ are included, this figure increases to 8%.

– In other roles, women comprised 10% of writers, 15% of executive producers, 25% of producers, 17% of editors, and 3% of cinematographers.

TELEVISION

IN FRONT OF THE CAMERA:

– 43% of all speaking characters and 43% of major characters were female in 2012-13.

BEHIND THE CAMERA:

– Overall, women fared best as producers (38%), followed by writers (34%), executive producers (27%), creators (24%), editors (16%), directors (12%), directors of photography (3%).

The situation in Australia isn’t much more progressive. According to Screen Australia’s statistics, in 2011 women represented:

– 40% of actors (that’s actually a steady decrease of 9% since 1996)

– 48% of authors (down by 2% since 1996)

– 23% of directors (a decrease of 1% since 1996)

– 24% of editors (down by 2% since 1996)

– 6% of cinematographers (unchanged since 1996)

But it’s not all doom and gloom: we make up 95% of make-up artists!

–

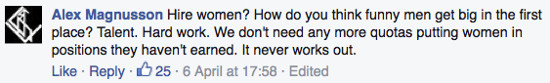

Hire More Women

It is not for lack of talent or hard work that women are not being represented on the small or silver screens. Maybe it’s because the entertainment industry ‘taste-makers’ are overwhelmingly white men who reward other white men, as in so many other fields. Women are not being given the same opportunities because ‘white male’ is just the accepted neutral.

For a recent example, just look at America’s current late night comedy re-shuffling. The leading US comedy talk shows have long been entirely monopolised by white men: David Letterman, Jay Leno, Conan O’Brien, Jon Stewart, Stephen Colbert, and more recently Jimmy Fallon, Jimmy Kimmel, Seth Myers and John Oliver. I’m not saying these guys aren’t awesome (Jon Stewart is my hero), but there should really be some women up there.

Just last week, Colbert was announced as Letterman’s replacement for The Late Show, despite some pretty formidable women’s names being thrown into the mix, including Ellen Degeneres, Tina Fey and late-night veteran Chelsea Handler. Whilst we can’t know for sure what conversations went on behind the scenes, we do know that Colbert had long been the front-runner (his contracts were even aligned with Letterman’s in anticipation), so it’s hard to believe any potential female hosts were seriously considered.

The two most historically successful female talk show hosts, Oprah Winfrey and Ellen Degeneres, are relegated to daytime slots because traditionally women were at home and their men out at work. Not only is this simply not the case anymore, but it perpetuates the great myth that men can only relate to men, that men would feel alienated watching a show hosted by a woman, and that a female host would be a niche, audience-limiting prospect.

The only way to level the playing field in such a male-dominated industry is to hire more women. While quotas are problematic and can potentially fuel a perception that women have not earned their positions, it’s clear that whatever we are doing right now isn’t working. In an ideal world, we would simply hire the best person for the job, but given the steady decline in female representation in the film and TV industry over the past 16 years, perhaps that stigma is something our generation has to bear. Our films are our stories — fictional or otherwise, they collectively represent our history and our identity. Women must be an equal part of that.

–

This is an edited version of an article that was originally published on the author’s website.

–

Alice is a filmmaker from Melbourne. She is currently living in an artist’s residency in Paris, where she eats croissants, acts pretentious, and tries to avoid dog poo. She hasn’t figured out how to use Twitter, but you can follow her movements at alicefoulcher.com.