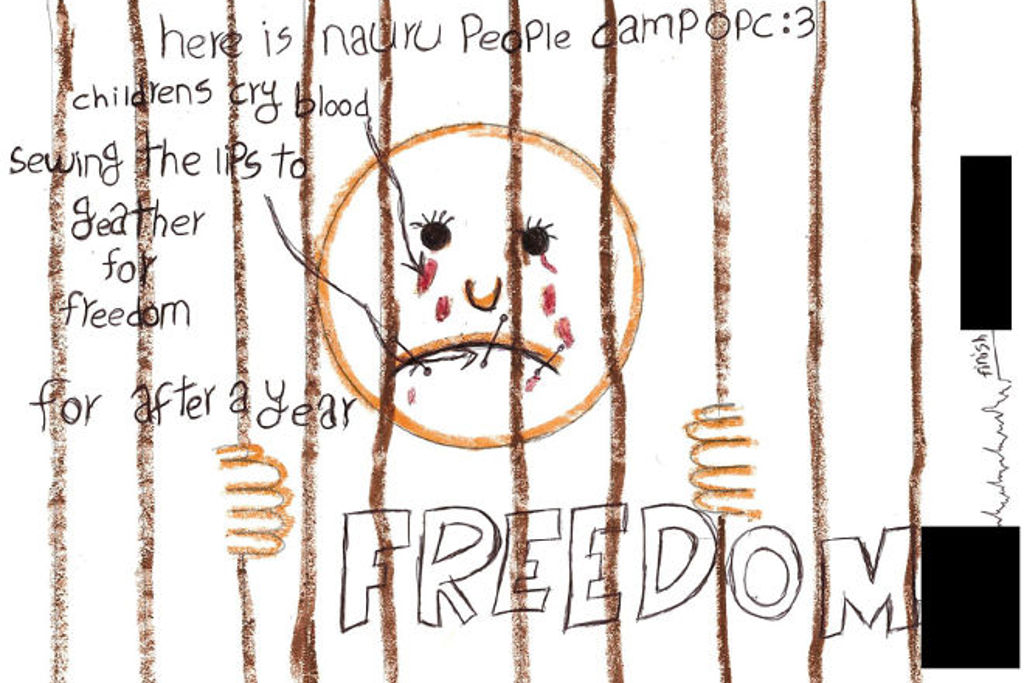

Around the beginning of last year, Australia’s broadsheets were covered in crayon.

With the Human Rights Commission’s Forgotten Children report tabled, more than 200 submissions were released to the public speaking from personal experience to life in offshore detention. This included typed letters, handwritten notes, and perhaps most alarmingly, drawings. In lieu of photos — journalists are largely prohibited in the centres — children in Nauru had given us their picture of the world.

This didn’t bring any salvation for those in detention.

A senate inquiry later found further reports of sexual assault, physical and mental abuse, and horrific living conditions. We’ve seen multiple claims of rape and a lack of adequate medical care. Between The Guardian‘s Nauru files detailing more than 200 other reports of abuse, and the forced closure of our facility on Manus Island, much of the country is desperate for change — though the true desperation comes from inside the camps. Just a few months ago, a 23-year-old Iranian man set himself on fire after screaming “I cannot take it anymore”.

It was with all this in mind that Australian photojournalist Isabella Moore travelled to Sweden earlier this year.

“Australia, like Sweden, is a party to the refugee convention,” Moore told Junkee. “They’re obliged to offer protection to people seeking asylum and cannot punish them for entering without permission or unnecessarily restrict their freedom of movement. They were both one of the first countries to become a State Party in 1954… [but in Sweden] I saw that refugees were taken care of regardless of how they came.”

While undertaking an arts residency in the southern Swedish city of Jönköping, Moore visited a temporary evacuation centre (in a space which was formerly a car showroom) called Oskarshall. “As Sweden, until recently, has been very generous with taking in refugees (around 160,000 between 2014-15) I wanted to see up close what the process for the asylum seeker looked like,” she says. “I thought it was a good time to help put the Australian policies into perspective by highlighting this differing humanitarian approach.”

“I was surprised to see that [the centre] had no fences and no security guards. The doors weren’t padlocked and the surrounds weren’t barb-wired. As a foreign freelance journalist it was easy to access the centre, I just had to explain my photo project to the manager and I was free to go ahead with it as I felt necessary — no questions asked. They trusted me.”

The resulting work paints a very different picture to those we’ve seen come out of comparable Australian sites.

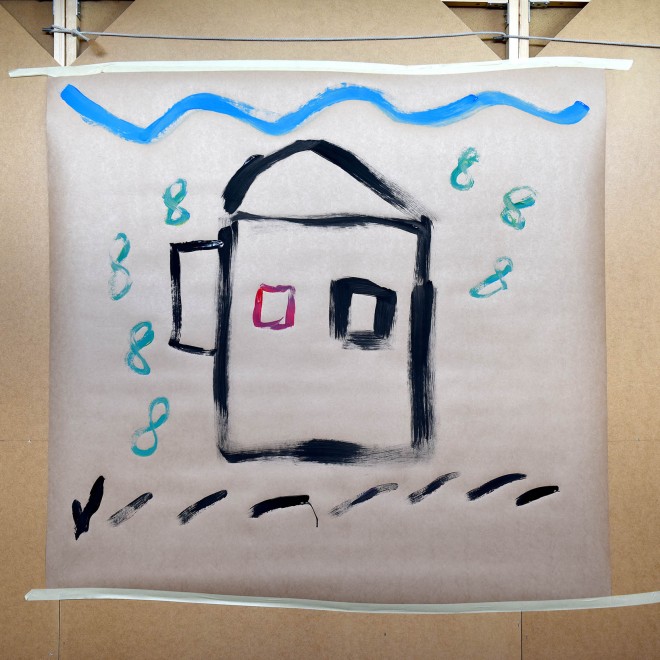

“FISK” (‘fish’ in Swedish) painted by Ayman and Moayed, both 11 years old, from Aleppo and Damascus, Syria.

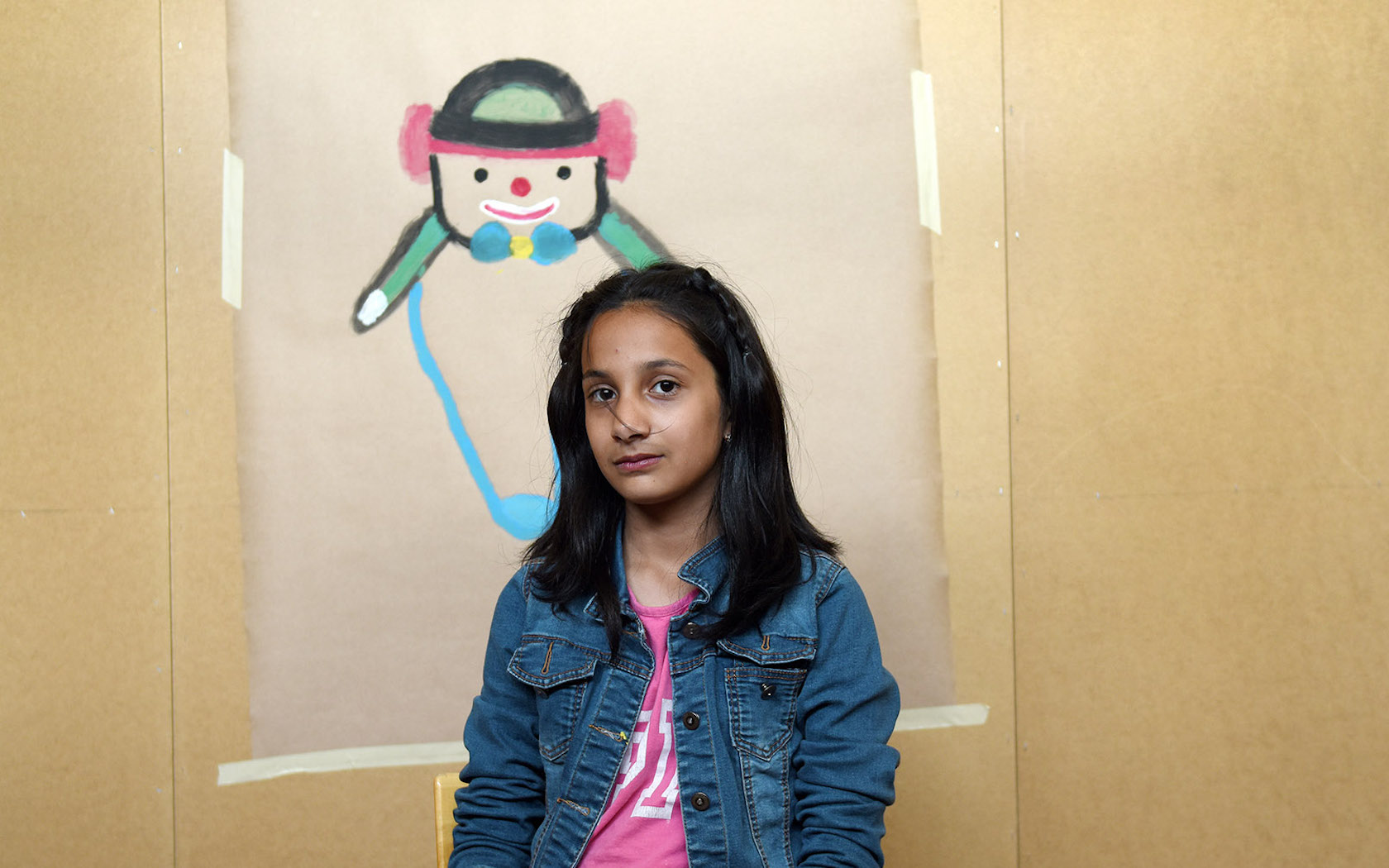

Moore’s project is essentially a portrait series, featuring a number of people living inside the centre; though it also features work from the refugees themselves.

“I didn’t want to stress [them] out and quiz them about their experiences of war,” she says. “I thought of a way to bring them some joy and, at the same time, get to understand a little bit about how they felt. I took a bunch of water-based paints, brushes and a large paper roll with me and asked people if they wanted to make a painting.

“You can read the rest from the pictures.”

Iman, 11 years old, from Kabul. Her painting was “Dolly”: a toy from the centre.

Oskarshall, the site Moore visited, was one of many smaller centres which popped up around the country to deal with an influx of refugees last year — an overflow from established centres in bigger cities like Malmö. The site was established in December 2015, when 150 people arrived in town by bus, and it housed a total of 200 over a six-month period.

As is fairly customary in Sweden, people stayed between one week and six months while waiting for the Migration Department to organise both their residency permit and temporary home. They were provided with a small stipend (which amounts to around $10.95 AUD per day) and allowed to fully interact with the community in which they were based.

“I observed that refugees were free to come and go as they wished,” Moore says. “They were housed, fed three meals a day, and given a small allowance for necessities, they were also given extra money if they needed medicine or wanted to see a doctor.”

“There were a large number of bedrooms [in the centre] with four to eight beds in each and, to allow for some privacy, temporary walls were set up between the bedrooms. The ex-manager of the centre, Lilian Lago, bought colourful cotton fabrics and sewed them into curtains to hang as doors at each bedroom opening, she also organised a deal with the local second-hand shop so families could visit and be sorted out with any clothes they wanted.”

Ayman and Moayed, both 11 years old, from Aleppo and Damascus, Syria.

This wasn’t the extent of the measures implemented to make refugees feel at home. Moore reports that Swedish families invited refugees into their home for Fika (a traditional coffee break) or social gatherings, and offered free Swedish lessons several times a week.

“I understood that parents were riding public transport to spend time in the city sightseeing with their children, and kids were learning to ride bikes (donated by the public) for the first time just outside the centre,” she says. “Friends of refugees could visit the centre and people could/would visit and interact with the refugees, as long as they came with a gesture of good will to offer.”

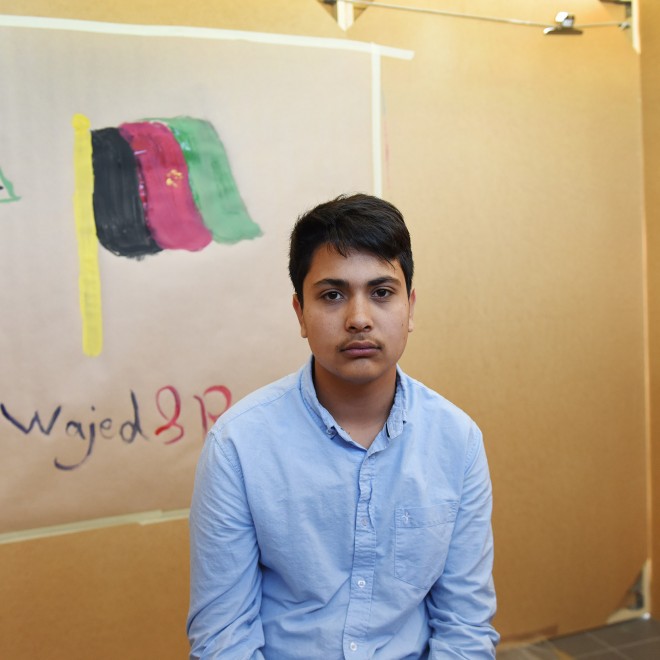

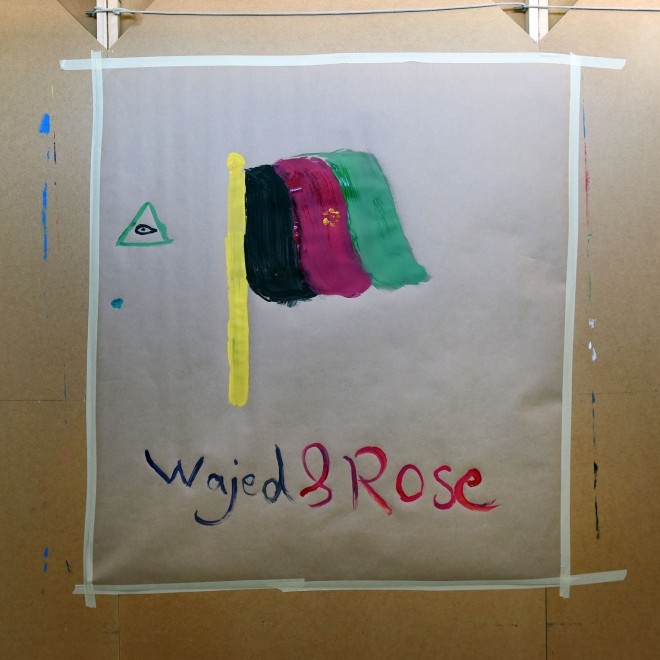

Wajed, 14 years old, from Kabul: “I miss Afghanistan”.

Sweden has long been praised for this humane approach to detention. Asylum seekers are accepted into the state’s care regardless of their method of arrival or lack of supporting documentation, and the system of being processed and integrated into the community is much more expedient. There are long-standing laws in place stating children can only remain in detention for a few days.

This has been well-noted by many in Australia. Way back in 2001, in an issue brief submitted to Parliament, Social Policy Group stated Swedish measures have resulted in “more open, more dignified and less stressful environments”. It also noted that, despite the fact “Sweden [received] more than twice as many asylum seekers per capita as Australia, fewer are detained”.

However, this hasn’t come without its problems. Once refugees are resettled in Sweden they’ve historically found it incredibly difficult to maintain employment. When the numbers of those seeking asylum got higher, the situation got worse — figures obtained from the National Audit Office by Bloomberg suggested a number of those who arrived in the country in 2003 were still seeking work in 2013.

Khaled, 25 years old, from Damascus. “This is the first thing I have ever drawn in my life,” he said. “Che is the reference to Guevara. For everyone they have a home to live in, except us, we have a home we live inside of.”

Late last year, when intakes amounted to 10,000 people per week (and Sweden’s yearly total was around 10 times that of their nearest neighbour, Denmark), the tide began to turn. Sweden’s Prime Minister Stefan Löfven announced tougher restrictions on borders and the introduction of temporary residency for refugees as the nation could no longer cope with long-term measures. Deputy PM Åsa Romson cried when she broke the news to the press.

Public sentiment was also affected around this time, and there were a spate of violent attacks aimed at refugees across the country. In October a man, motivated by racial hatred, brought a sword into a school with a high population of migrants and killed two people. One day later a detention centre burned down in a suspected arson attack. Swedish media outlet The Local report there were 18 further attacks on centres in the three-month period which followed.

The European refugee crisis is just that — a crisis — and Sweden is not without problems because of it. There are too few homes and jobs for those in need and too many people channelling their fears about that into violence and hate. It’s the same situation playing out all around the world. But, this cruelty hasn’t yet defined the nation. Sweden is still full of sites like Oskarshall where, as Moore puts it, “everyone is treated with human dignity”.

It’s an awfully low bar to shoot for, but Australia isn’t there yet.

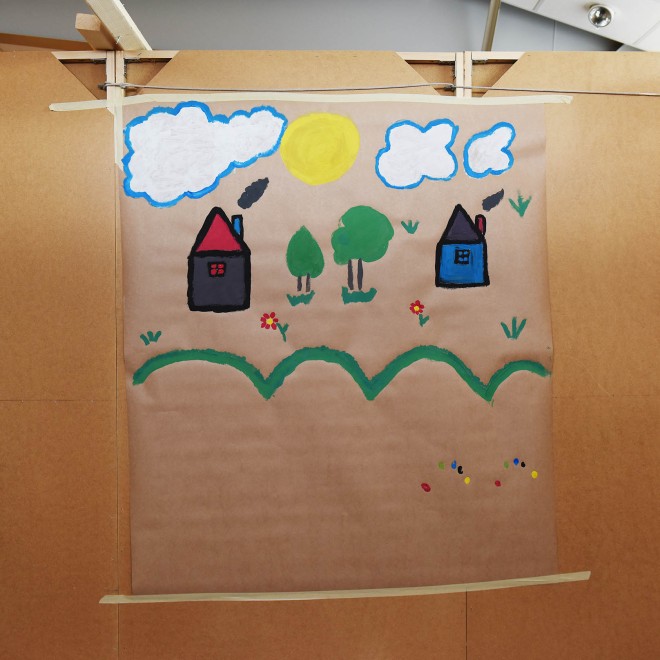

Atifa Razia, 12 years old, from Mazar-i-sharif, Afghanistan. She described her work as “a place to stay at home, relaxed in the countryside”.

–

Check out the full series here:

–

Isabella Melody Moore has worked for various news publications as a staff photographer and contributing photojournalist since 2010. She has worked regularly for News Corp and been published by The New York Times, The Guardian UK, The Observer Magazine UK, The New Internationalist, Frankie, Yen Magazine, and more. See more of her work via her website or Instagram.