What Is The Debate Around Australia’s Race Hate Laws Really About?

Surprise, surprise, it's mainly about Andrew Bolt.

Australia’s most influential conservative voices have been raging against the country’s race hate laws since roughly 2011. After Andrew Bolt was successfully sued for racial vilification, the debate around Section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act became a key battleground in Australian politics and it’s showing no signs of stopping.

This week, a broad coalition of community groups signed a joint letter in support of the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) and Section 18C — the main federal law against racial vilification. The letter is a response to the ongoing debate around Australia’s race hate laws that has become a key focus for sections of the conservative media. Crikey has reported that in just three months The Australian wrote 135,000 words on Section 18C. That’s the length of a decent sized novel.

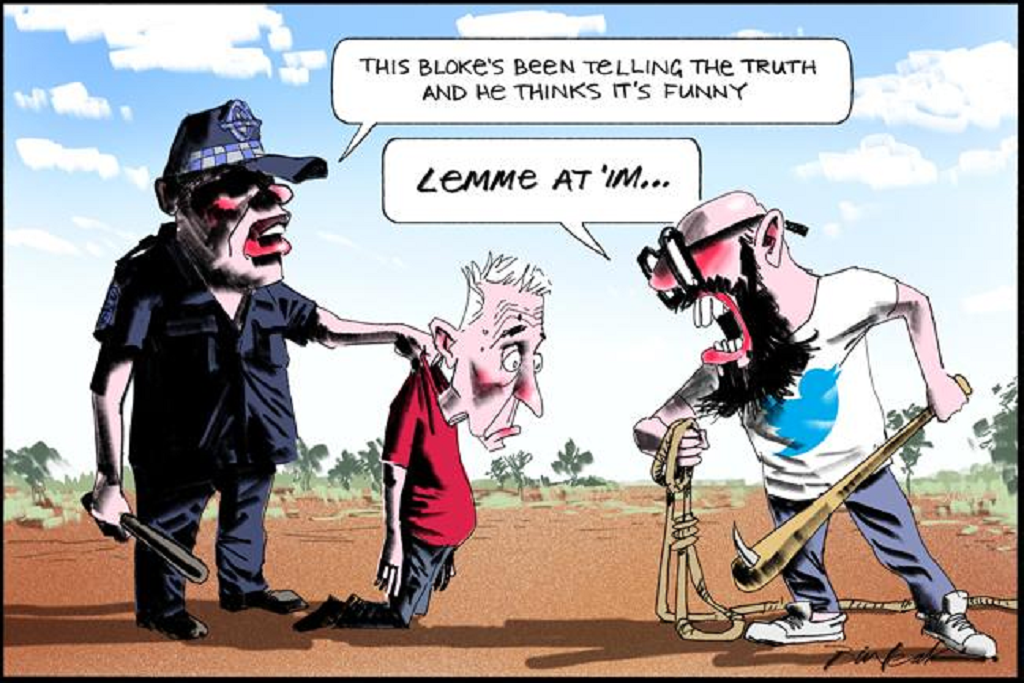

More recently, the political controversy on the issue has focused on two high-profile cases. The first relates to News Corp cartoonist Bill Leak, whose cartoon depicting a drunk Indigenous father was referred to the AHRC. The second matter relates to a group of three students from the Queensland University of Technology who allegedly posted offensive comments on Facebook.

In response to pressure from the media and the right-wing of the Liberal Party, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull has initiated an inquiry into the Racial Discrimination Act which will examine how the AHRC deals with race hate complaints.

The joint letter, which has been signed by groups including Amnesty International, the Asylum Seekers Resource Centre, Australian Muslim Women’s Centre for Human Rights, Get Up!, the Federation of Ethnic Communities’ Councils of Australia and Reconciliation Australia argues that both the Racial Discrimination Act and the AHRC are working well to protect Australians from racism.

But despite the support from groups representing Australians from culturally diverse backgrounds, Section 18C is still under attack from those who believe it’s an unnecessary restriction on freedom of speech. They want the law amended or even abolished.

–

How Does Section 18C Even Work?

Section 18C makes it unlawful for someone to “offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate” another person, or a group of people, on the basis of their race, colour or national or ethnic origin. If an individual feels like the law has been breached and they’ve been racially vilified, they can make a complaint to the AHRC.

The AHRC has a responsibility to try and mediate those complaints, and the majority of them end up being resolved through that conciliation process. However a small number of complaints (about 3 percent) end up being pursued through the courts because either of the parties weren’t happy with what the AHRC recommended.

In those instances it’s up to a judge to determine whether the law has been breached. That’s what happened when Andrew Bolt was accused of breaching Section 18C in 2011.

Bolt had written a column where he accused fair-skinned Indigenous Australians of using their identity to win grants and prizes. A judge found that Bolt had breached the law and concluded that “fair-skinned Aboriginal people (or some of them) were reasonably likely, in all the circumstances, to have been offended, insulted, humiliated or intimidated by the imputations conveyed in the newspaper articles.”

–

Why Is It So Controversial?

Conservatives have never really liked Section 18C because they think it impinges on freedom of speech. But it wasn’t until Bolt was successfully sued that a co-ordinated push to weaken it, or remove it altogether, really gathered steam.

Former Prime Minister John Howard said recently that the law “didn’t seem to matter” when he was in charge and it took the Bolt case for people to realise “how potent this thing was”.

Since Bolt lost his court case, right-wingers like Tony Abbott, Cory Bernardi and David Leyonhjelm have been agitating for 18C to be amended. Bernardi has already announced he will introduce a bill to remove “offend” and “insult” from the Act, meaning someone will only be acting unlawfully if they humiliate or intimidate another person based on their race. Pauline Hanson and Derryn Hinch also want 18C weakened or removed.

The Bill Leak case has also become a bit of a lightning rod for conservatives. Andrew Bolt and The Australian have been running a “Je Suis Bill Leak” campaign, comparing the cartoonist to the Charlie Hebdo magazine that was targeted by terrorists, which seems wildly over the top.

One of the problems with the current debate is how polarised it’s become. You’re either in favour of Section 18C ,in which case you hate freedom and democracy, or you’re against it, which means you’re a giant racist.

In reality, the issue is much more complex, and something that’s become clear through the political brawl is the fact that many commentators don’t actually understand how the law works in practice, or what the role of the AHRC is.

–

Cutting Through The Bullshit

Influential conservatives like Andrew Bolt, along with the conservative wing of the Liberal Party, really don’t like the Australian Human Rights Commission. In particular, they aren’t great fans of the Commission’s president, Gillian Triggs.

Triggs has publicly condemned the government’s refugee policies, which has made her a target of many on the right-wing of Australian politics. But recently, the focus of the attacks has moved to another key AHRC figure: the race discrimination commissioner, Tim Soutphommasane.

Soutphommasane is responsible for the AHRC’s handling of complaints under Section 18C. And as we’ve already established, conservatives really don’t like 18C. But the problem is a lot of the commentary in terms of how the AHRC deals with complaints seems to misrepresent their responsibility.

Last month Malcolm Turnbull said “I think the Human Rights Commission has done a great deal of harm to its credibility by bringing the case against the Queensland students”, referring to a complaint made regarding their alleged behaviour.

In 2013 Cindy Prior, a staff member at the Queensland University of Technology, made a complaint against a group of students for allegedly posting offensive comments in a Facebook group after they were asked to leave a computer lab reserved for Indigenous students (the students in question were not Indigenous).

The AHRC conciliation process in response to the complaint failed and Prior took her case to the federal courts. But the important thing to note here is that it wasn’t the AHRC who brought the case, as Turnbull suggested. It was Prior.

Here’s the thing: the AHRC doesn’t bring cases against anyone. Its role is to mediate complaints. If individuals choose to reject that mediation and take a case to court, that’s their prerogative. It’s not the fault of the AHRC.

Seventy-six percent of the AHRC’s 1,308 conciliations are actually successfully resolved. So it seems like Soutphommasane and his team are doing their job. Whatever problems people might have with the law itself should be fairly debated, but blaming the AHRC misses the point.

So what about the law? Does it really restrict freedom of speech?

Ultimately, that’s a matter of perspective. Free speech purists will argue that there should no restrictions whatsoever. Supporters of Section 18C argue that not everyone has the ability to engage in public debate equally, and there should be protections to stop newspaper columnists and cartoonists, for example, racially vilifying minority groups.

Often the debate around Section 18C ignores the very relevant law that follows immediately afterwards: Section 18D. Section 18D actually creates a whole bunch of loopholes which makes offensive speech legal, if it meets certain conditions.

According to the AHRC, Section 18D ensures that “artistic works, scientific debate and fair comment on matters of public interest are exempt from section 18C, providing they are said or done reasonably and in good faith”.

Most of the people unhappy with how Section 18C works right now want to remove the words “offend” and “insult” from the Act. They think those words are too subjective. But the community groups who signed the joint letter argue that the evidence suggests the law works well now, there are enough exceptions and the AHRC and judicial processes are robust enough to ensure the law is upheld fairly.

While the debate around freedom of speech has focused almost exclusively on Section 18C, other commentators have pointed out there are plenty of other laws that restrict speech in potentially more harmful ways. Defamation law, restrictions on immigration detention centre workers from speaking out and suppression orders are just some examples of laws that currently severely restrict freedom of speech. They can stop people reporting on government policy and hamper the work of journalists in holding powerful interests to account.

Getting the balance right in our race hate laws is important, but at the moment, the level of debate is pretty underwhelming. We should start by making sure people properly understand how Section 18C works, and widen the discussion around freedom of speech to include all the laws that could restrict it — not just those targeting racial vilification.