Sponsored by Contiki

In 2011, Christchurch was a live city curled around a broken centre. The earthquake that hit in February that year saw nearly three quarters of the buildings in the city centre either collapse or be damaged to the point of demolition. The entire area was deemed unsafe, not just for habitation but any public presence. The army was sent in to maintain a blockade, and the slow process of assessing and stabilising the damage went on for years.

As will always happen, some people didn’t like being told what to do. Whether it was fascination or a resentment of authority or the simple acceptance of a challenge, explorers found ways into the banned zones.

Some of them just looked around, climbing the shells of buildings before making their quiet way out. Some of them probably just sat and smoked or passed a bottle. Some would have gone to pay tribute to lost people or places. But some of them, as in almost any city in the modern world, went there to paint.

Ballerina’ by Tauranga artist Owen Dippie. (Image by Jocelyn Kinghorn)

–

For graffiti artists, the ruptured city opened up an unprecedented field of opportunity. Everywhere were unused walls, strange structural configurations, newly exposed surfaces. Whole facades of buildings had peeled away in life-sized dollhouse parody, revealing the levels within. None of it could be salvaged, nothing used. Concerns of ownership and appearance evaporated. Overnight, property became worthless. The modern way of understanding public space had changed.

A lot of the painting was basic: tags, scrawls, graffiti as the existential howl that it remains at its simplest level, or a means of marking areas that had been explored. But the artwork quickly grew more complex, and soon enough major murals were starting to take up whole walls.

And where graffiti is so often met with social antipathy, these images began to have a different effect. They were bright and colourful, or artful, or poignant, or funny, a point of variation or emotional connection in the middle of a landscape that was dominated by ruination and rubble and various shades of grey.

As these things go, momentum generates momentum. People saw what was happening and were compelled to respond in kind. Artists from outside Christchurch heard about it and came to add their contributions. Very soon, people locally who had nothing to do with graffiti came to see this local iteration as representing them. It was a sign that not all was lost; the first that someday people would be able to take their town back.

Banksy in the Canterbury Museum.

–

George Shaw And The Rise Of Spectrum

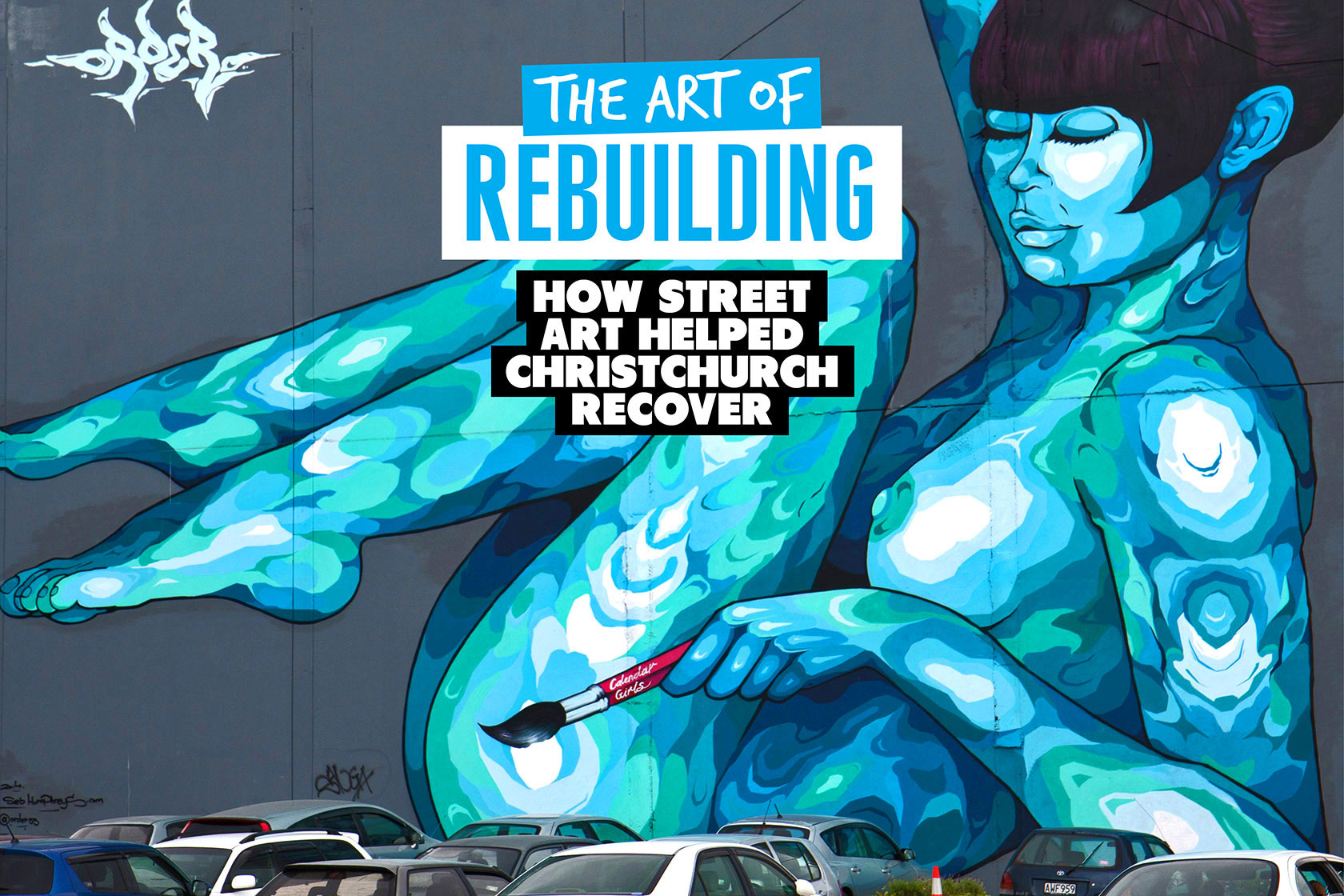

It’s not always beloved: some of the worshippers at the temporary cardboard cathedral designed by Japanese architect Shigeru Ban were less than delighted by the ethereal blue naked woman curled across several stories of concrete across the promenade from their front door. It probably doesn’t help that she’s on the wall of a strip club.

But street art has come to represent Christchurch in a bigger way than anyone imagined. Five years after the earthquake, the city is laced together by more than 50 major murals. They hang above bulldozed car parks. They spring into view as you round corners or pass other structures. There go Vexta’s fluorescent fractals. Here is ROA’s roof-high decoration of the extinct moa bird. There is one of French artist Seth’s sweetly naïve child observers. The city is still a mess, part demolition zone and part construction site, vacant lots of rubble or condemned lots fenced off on every block. Between all this appear the murals, a unifying theme amongst so many ruptured connections.

This atmosphere is what first drew George Shaw to Christchurch. It’s a great story: Shaw was already in his middle age and living in his native England when he fell in love with Banksy’s work in 2005. In one of the supreme acts of hipster one-upmanship, he amassed the world’s biggest Banksy collection before the ultra-famous artist got famous. By then Shaw was in love with street art more broadly. He also decided to move to New Zealand after a visit. By 2013, he heard what was happening in Christchurch and decided to get involved.

Shaw was central to curating Rise, the city’s first street art exhibition, in 2013. This included the massive Final Act installation, where Australian artist Ian Strange performed radical surgery on entire houses in the city’s suburban Red Zones to create a light show before they were demolished. It also included commissioned murals around the city.

After a comical run-in with a fly-fishing film festival of the same name, Christchurch’s Rise Festival became Spectrum Festival for its next edition. The second Spectrum wraps up this April. Partly it involves more murals out in the city, while the other part is housed within the substantial confines of the Christchurch YMCA building. As Shaw walks us through the different stages of the exhibition, its ambition and scope emerge.

–

Living In The Red Zone

The entry point is a deliberately cheesy homage to the felt-tip marker, key tool for tagging and sketching since the very beginning of the genre. Here it is edited into iconic movie posters and a wall-sized riff on The Jetsons. But things quickly get complex with the offering from Sofles, who you would likely remember from a famously brain-bending YouTube clip called Limitless that he made with another contributor to this exhibition, Selina Miles.

Here his painting is segmented across sheets of Perspex, each hanging from the ceiling a metre or so from the next. You walk between them – left, up, right, up – like an airport check-in queue. As you look back, more of the picture emerges. Only after the last frame can you try to line up all the component parts for the final image. Sofles spent three days staring at the Perspex, figuring out how to approach the job, before he even picked up a can of paint.

From there you arrive at an installation rich with resonance. “The foremost street artists from this city are called the DTR crew,” explains Shaw. “We tasked them with creating an urban jungle, and they decided to replicate a scene from that Red Zone that was fenced off in the central city.”

When you grasp the context, the effect is stark. You stand in a ruined office: water-damaged roof panels, mouldering furniture. Everything – desk, walls, computer monitor, even the telephone – is slashed in fluorescent tags, yet it retains enough sense of its office-ness that people walking through the exhibition apologise on entry for interrupting our work meeting.

Through a slumped doorway you enter the next phase, an external environment under the YMCA’s high roof. One wall is a recreation a building with the side gone, pipes and toilet tanks jutting out high above. A power pole caked in bird shit stands in one corner. Occasionally trains pass or barking dogs are heard on background speakers. The effect is eerie. But you’re not alone. Look closely in the office and a battered TV monitor is showing grainy CCTV vision. On it you can see the DTR crew – Wongi Wilson, Icarus, and Jacob Yikes – graffing another corner of this notional building.

The other parts of the exhibition are all worth attention: Milton Springsteen’s corrupted classics; the fractured Kiwi forest scene by “one of the country’s foremost artists of a generation” in Flox; the Miles video installation with 171 projected channels of street artists at work around the world; the tribute to 1960s New York when Taki 183 first spawned tagging; and the moment of beautiful, humorous revelation when you walk down a sombre tunnel towards a shrine, only to emerge and realise (spoiler alert) you’ve come down the barrel of an enormous, immaculately constructed felt-tip marker pen.

Along the walls of the final hangar are similarly proportioned spray cans, metres high, each painted by one of the contributing artists to the exhibition. Where you expect a street art exhibition to be a few photos of murals, the commitment to complex installation work makes Spectrum stand out a mile.

More amazing Christchurch Street art – this place has been a revelation – especially the Spectrum exhibition pic.twitter.com/yEjguu8Ua1

— Matt Jukes (@jukesie) March 12, 2016

But what really stays is the DTR section: that memory of life in the aftermath, and the reality it reflects. Some of the younger people in Christchurch express a wish to stop talking about earthquakes. It’s understandable. They have lives to get on with.

But not everyone can do it. The wall of the installation features a stylised self-portrait of the three artists. Like so many, what happened in Christchurch is part of what defines them now. Nor is it just part of the history: it’s part of the present. Cue Shaw in the room of the Miles installation. “See where the frame has kicked out a little bit, that top projector?” he had said. “That would have been from a quake the other day.”

–

Pay homage to Christchurch and the land of adventure – save up to 7.5% on New Zealand trips with Contiki. Check out trips NOW!

–

Geoff Lemon is a writer, radio broadcaster and editor of Going Down Swinging. Geoff would like to thank Christchurch & Canterbury tourism for their help with this article.

Sponsored by Contiki