‘Chasing Asylum’ Is A Must-See Documentary Exposing Australian Detention Centres To The World

This is what our migrant films look like in 2016.

Many things can propel somebody to make a movie, but for director Eva Orner, the impetus was simple: shame. “I thought I needed to make a film to shame Australia internationally,” she has said on the press tour for her new movie, Chasing Asylum. “Also, [I wanted] to educate people in Australia about what’s happening.”

Having already won an Oscar as a producer of Alex Gibney’s Taxi to the Dark Side (2007) — which helped shed light on the in-custody torture of detainees by the American government following 9/11 — the Melbourne-born filmmaker is now doing the same for asylum seekers. Considering the ridiculous to downright offensive rhetoric around the debate in Australia, she could have been forgiven for thinking the plight of refugees was just too much; an issue too monolithic in its scope and implications. But with statistics, news footage, whistleblower testimonials, and — most importantly — secretly filmed video taken inside the offshore detention centres of Naura and Manus, her new documentary has absolutely fulfilled her goal.

–

Anonymous Content

It’s ultimately these covert videos that separate Chasing Asylum from any number of other reports on Australia’s treatment of refugees. Recorded anonymously with cameras hidden in satchel bags or coat pockets, they reveal the first-hand tedium and squalor that many of these detainees face.

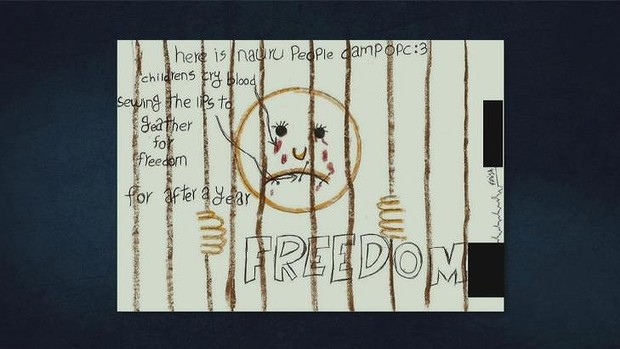

There’s disturbing graffiti sprawled across cement walls, drooping tents that are riddled with mould and WWII-era tin sheds that hide sweltering women and children. We also see first-person accounts of kids’ minds deteriorating without stimulation or education; and, most disturbing of all, the children’s drawings handed over in secret, away from the watchful eyes of the guards, that detail their pleas for the suffering to be over.

In one of the film’s most compelling moments, one of the anonymous videographers is revealed as a guard whose camera catches other employees calling the detainees horrible names with a complete disregard for human dignity. Others brave enough to put their face on camera include social workers who detail their own horror stories of needing to know how to cut down people who have hanged themselves, the daily self-harm they witnessed, as well as the rationale behind successive governments contributing to this system.

As cameras and recording devices are not permitted in these facilities, Orner has spent months traversing legal minefields in order to release the film uncut. At a post-screening Q&A in Melbourne, she confirmed she and her crew are under no threat of jail time. Nevertheless, the danger the people filming these videos are clearly in at the time comes through loud and clear as they are seen protecting themselves and those in front of the lens.

It’s as incendiary a work of documentary filmmaking that this country has produced in quite some time.

–

A Nation Built On The Backs of Immigrants

If Orner’s mission was to spark a bigger, national conversation on this issue then she is in no shortage of company among Australian artists. Recent theatrical productions like John Kachoyan’s Elegy covered the subject of asylum seekers head on, as did the SBS series Go Back to Where You Came From. Our cinematic history is littered with broader migrant stories too, sometimes even from those who made a perilous journey themselves.

While the early days of Australian film were dominated by stories of battlers, blokes, dames, and war-time adventure, this changed dramatically in the 1960s. Giorgio Mangiamele, a photographer from Sicily, migrated to Australia and went on to direct a series of films detailing the Italian migrant experience in Melbourne in a style reminiscent of Italian neorealism. In The Contract (1953), The Spag (1962), Ninety-Nine Per Cent (1963), and the Palme d’Or-nominated Clay (1965), Mangiamelli’s characters all faced antagonism from white Australians who viewed them with suspicion as uneducated thieves; out to steal jobs from the rest of us (sound familiar?).

These themes have remained popular with filmmakers ever since. Khoa Do (Mother Fish, Falling for Sahara), Tony Ayres (The Home Song Stories, Saved), and Solrun Hoaas (Aya) — from Vietnam, China, and Norway respectively — have brought their unique perspectives to stories of migration. Meanwhile, the European immigrant experience is a heavy part of what endeared wider audiences to titles such as Looking for Alibrandi (2000), Head On (1998), and The Heartbreak Kid (1992); all films in which characters struggle with the demands of their cultural heritage and the promise of freedom found in modern Australia.

These films and many more like them all deal with ideas that spring forth from this country’s past of inclusionary immigration that the central figures of Chasing Asylum will likely never be afforded. What would our country look like, socially and culturally, if we didn’t take in refugees after WWII or — as one of the film’s most pertinent segments suggests — then PM Malcolm Fraser turned away the troubled people of Vietnam in the 1970s?

–

Stranger Than Fiction

Of course, unlike those other films that have the benefit of having romance or comedy or just general cinematic artifice to keep the audience at a remove from reality, there’s no escaping the harsh, brutal truths of Chasing Asylum. The effect of Orner’s film is so potent that it will no doubt leave viewers, much like it did myself, in a mixture of stunned silence and blinding rage.

Orner’s film covers much more than just Nauru and the island of Manus too. With camera in tow, she visits Cambodia (where only a few refugees have been resettled), Afghanistan (where a family tells of hearing about their son’s death in detention), as well as showing us life aboard a boat full of asylum seekers — one of whom claims they want to move to Australia because they’ve heard it is a safe and humane country that respects refugees.

Like Taxi to the Dark Side, Orner’s film takes umbrage with a government that appears to be making up the rules as they go along. The hypocrisy of the actions of Parliament going right back to the Howard years is made blatantly obvious, and Chasing Asylum will hopefully cut through the second-hand hearsay and show these detention camps for exactly what they are.

The other film that Chasing Asylum recalls is Citizenfour, which committed a documentary coup of its own by having filmmaker Laura Poitas in the thick of the action as Edward Snowden leaked the NSA files that the US government didn’t want to know about, let alone see. Just like that movie, Orner’s goes beyond mere reporting and in fact becomes the news.

Chasing Asylum is a film that ought to be seen and discussed by all Australians whether they are for or against the government’s current policies. It’s hard to fathom anybody watching it and not being moved. The politicians are the ones really shaming and disgracing this country, Chasing Asylum just finds new and compelling ways to show it.

–

Chasing Asylum is in cinemas now.

–

Glenn Dunks is a freelance writer from Melbourne. He also works as an editor and a film festival programmer while tweeting too much at @glenndunks.

–

RELATED: More Than Mad Max: The Amazing Docos We Miss When We Talk About Australian Film