Cool Prisons, Women’s Rights, And Other Heaps Fun Stories From Australian History

Ahead of this weekend's Australia Day festivities, let's reflect on some of our better achievements.

Australian history and how it’s taught in schools is back in the public eye after Christopher Pyne heroically announced plans to save the minds of the nation’s youth from the lurking threat of Communism by revising the national curriculum to remove “partisan bias” and refocus it on “important events in Australia’s history” like Anzac Day, Federation and presumably Bob Menzies’ birthday. While listening to Pyne go on about ‘Straya (or anything) is about as aesthetically pleasing as a night of Jim Beam and Indian food, renewing the conversation around what we teach kids about our country could be something of an opportunity, because there’s a far bigger problem with the current Australian history curriculum than its chronic Freedom deficiency.

As any high-school student will tell you (using words like “totes” and other terms you don’t understand), it’s really, really boring — so boring that it turns most people off Australian history for life. This is the worst, because Australian history — not the Phar Lap-Don Bradman bowl of porridge they forced on you at school, but the actual things that happened — is friggin’ amazing. If we’re going to rejig the curriculum, we could do a lot worse than squeezing these awesome bits of our history in before that last week of the semester where the teacher just chucks on School Of Rock.

–

We Basically Invented Modern Democracy

In the mid-1800s, the ‘democracy’ most people got was kind of like skim milk: it looked like the real thing, but was just objectively not as good. In England, for example, you couldn’t vote in secret — your vote was recorded next to your name, which meant that if Lord Alan Jones’ grandfather was running for Parliament, he’d know if you didn’t vote for him and probably kick you off the dirt farm you worked on his land. More recently, dictatorships that hold sham ‘elections’ get the result they want by recording who votes for them and beating up or imprisoning whoever doesn’t.

In 1838, a bunch of righteous dudes called the Chartists decided the situation was, to use the parlance of the time, straight whack. They got together and published the ‘People’s Charter’, calling for the right to cast our votes in secret and other dangerous poor-people ideas like letting all adult men vote and paying Members of Parliament so regular people could afford to run. England’s rulers responded to the Chartist’s demands by sending cops to smack them around and then packing them off to Australia, the Empire’s all-purpose human wastebasket. Australian colonial elections were just as corrupt and unrepresentative as British ones, but England’s super-strict class hierarchy was pretty hard to enforce in a place where you needed ex-cons to grow your food, giving the Chartist leaders the wiggle-room they needed to gather support and pressure colonial governments into not acting like the Plastics in Mean Girls.

In this analogy, the Plastics are colonial governments, fat Regina George is the Chartists, and “sit with us” is participating in democracy. It is a flawless analogy.

Cut to 1854 when a couple of grubby miners in Victoria formed the Ballarat Reform League, which issued Chartist-inspired demands for fair representation and to not be ripped off all the time, please and thank you. The Victorian government responded exactly how the English one had in 1838, but the miners flipped them the bird, got someone’s mum to stitch a flag together, and the Eureka Rebellion happened. While the Rebellion didn’t pan out because soldiers have lots of guns and miners don’t, the Eureka miners became heroes overnight, the leaders of the revolt were acquitted of treason, and colonial parliaments started passing laws basically gifting the Chartists everything they couldn’t get in England, including the secret ballot — the first laws to do so anywhere. The secret ballot took off all over the world like parachute pants in the ’90s, and to this day is the gold standard for countries adopting democratic reforms. It’s other, widely-used name? The ‘Australian ballot‘. You’re welcome, everyone else.

–

We Were Into Women’s Rights Before It Was Cool

Most people know in a vague way that Australia was the second country to grant all women (except Aboriginal women, in some states) the right to vote after New Zealand, and if you didn’t know that, we super did and go us. That’s pretty much everything you learn about Australian women’s suffrage at school, which makes it seem like women were just gifted the vote without having to do anything. That’s wrong, sister — the suffragettes worked their petticoated butts off, touring the country and collecting thousands of signatures on petitions in the days when signing a petition meant, like, picking up a pen and writing your name, which just seems like SO MUCH WORK now. They didn’t even get to tweet about it after.

It is true, though, that the old white moustaches who ran the show back then were much less douchey on the women’s suffrage issue than the old white moustaches elsewhere. In the late nineteenth century, Australia was pretty much a giant experimental greenhouse for new ideas that couldn’t get a run in older democracies like America and Europe. Women’s suffrage in Australia was already a done deal when governments in England and the United States were fighting tooth-and-nail to keep women out of the voting booth, let alone political office. When Australian women scored voting rights federally in 1902, they also became the first women to win the right to run for office, dooming us to the eventual man-hating Juliartatorship we somehow survived together. Even so, the fact that the suffragettes didn’t have to resort to throwing themselves under freaking horses to get their natural rights like they did in England is pretty great.

Also, those people you’ve never heard of on our money with the illegible signatures? About half of them were awesome trailblazing ladies. Australia’s first female politician, Edith Cowan, ran against the Attorney-General who introduced the law giving her the right to run into Parliament, beat him, and used her new platform to promote sex education in schools. Baller move, Edith. Catherine Helen Spence was the first Australian woman to stand for office — in 1897 guys, come on, give it up — and campaigned her whole life for proportional voting to make elections fairer. After Spence died, she was given the title ‘Grand Old Woman of Australia‘, which is officially the most swag title to ever swag. They’re on the five and fifty-dollar notes respectively (not the five-dollar note with the Queen on it, the other one), so while you’re mainlining House Of Cards on the couch, they’re up in Cool Old-Lady Heaven making it rain forever using cash money with their own faces on it.

–

We Cured Prison Forever, But Then We Forgot

You know the third season of The Wire, where Major Bunny Colvin makes a last-ditch effort to keep The Game out of honest neighbourhoods by setting up zones where dealers and addicts can do whatever they want? And it works super well, with crime plummeting and whole city blocks coming back to life? And when his gambit gets found out, the whole grand scheme gets shut down and Bunny is forced to resign in disgrace? It’s an incredible story, but no one would have the guts to pull a stunt like that for real, right?

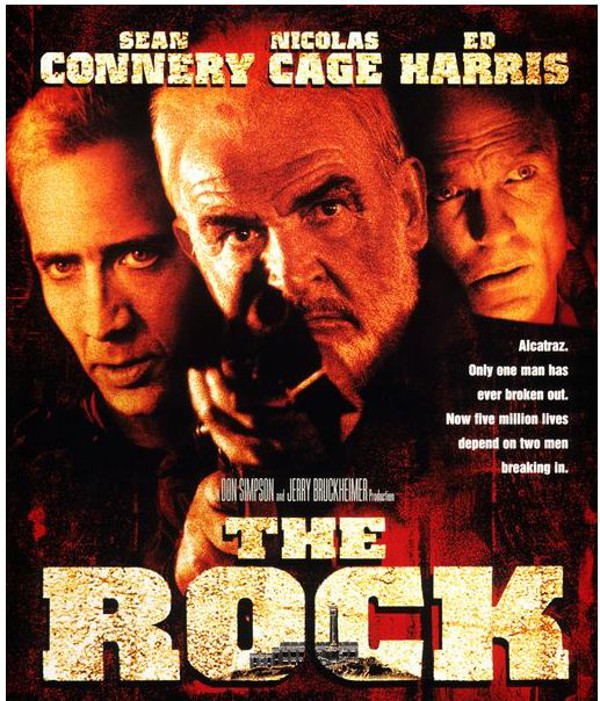

Wrong, sunshine. Scottish-born prison commandant Alexander Maconochie — aka the most amazing guy you’ve never heard of — did that exact thing, only on an island fortress prison in the middle of the Pacific around the same time the postage stamp was invented. In 1840, Maconochie was appointed superintendent of the Norfolk Island penal settlement, a place reserved entirely for the worst of the worst: murderers, rapists, and serial offenders deemed beyond any hope of living in decent society. Norfolk Island was basically Super Alcatraz — a hell on earth in the middle of nowhere, where convicts were treated so appallingly that they would draw straws to be stabbed to death by their cellmates as a form of assisted suicide.

Once in charge of this island hellhole, Maconochie made the classic first-day prison move of finding the biggest, baddest mother in the yard and knocking his ass out to establish dominance. Oh wait, no he didn’t — he called 1,200 prisoners together and told them that the old system of floggings, confinement and general hideousness that had gone on for years was over. Maconochie’s assumption, beyond radical for its time, was that even the worst offenders could be rehabilitated if they were treated with respect and given the opportunity to better themselves. In his four years running Norfolk Island, Maconochie ordered books and magazines for a library, started classes to teach convicts skills like carpentry and gardening, gave every prisoner a plot of soil to grow their own food, built churches and set up a synagogue, dismantled the island’s gallows, and set up gravestones for convicts who died.

As word of the new system got out, colonial Australia went berserk. Newspapers and politicians called Maconochie a madman and predicted that the bloodthirsty criminals he was treating so liberally would soon kill everyone in authority, escape to the mainland, and start a convict rebellion, Con Air-style. What actually happened went like this: to celebrate the Queen’s birthday one year, Maconochie let the convicts out of their cells and treated them to a day of food, rum, entertainment and fireworks, paid for with his own money. Obviously, as soon as they got outside the prison walls, these hundreds of newly-unleashed criminal maniacs took advantage of Maconochie’s naivety, banded together and — oh, they put on a musical. And some poetry readings.

And tossed back their glorious, flowing hair.

It couldn’t last — Maconochie was sacked by a government convinced he was a lunatic, and his replacement turned Norfolk Island back into a hell on earth. Maconochie died in England years later completely forgotten, his ideas regarded as a bad joke. The only upside to the whole experiment was that it totally worked — of the 920 prisoners Maconochie released to the mainland during his tenure, twenty re-offended. That’s a two per cent re-offender rate. The current re-offender rate in Australia? 60 per cent. The guy basically cured jail at a time when the default way of dealing with criminals was “send them around the world where we don’t have to look at them”. He deserves his own national holiday or, at the very least, a ten-part HBO mini-series starring Guy Pearce.

–

Alex McKinnon is a Sydney-based writer and journalist who will finish his Arts degree one day, swear to God. He is the former editor of the Star Observer, Australia’s longest-running LGBTI weekly newspaper.