Australia’s Getting A Seat On The UN Human Rights Council Despite Our Many Human Rights Abuses

In what world are we a "human rights leader"?

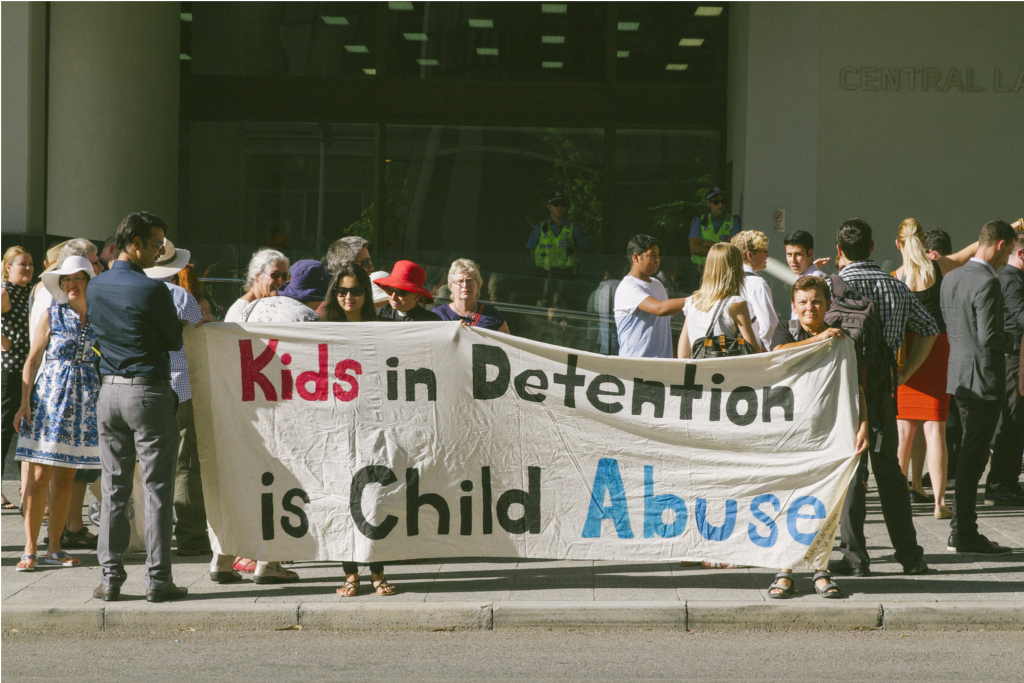

Well, Australia’s finally gonna get its wish. Later today, we’ll get a seat on the UN Human Rights Council, despite our human rights record featuring unacceptably high numbers of Indigenous deaths in custody and an offshore detention policy that breaches the UN Convention Against Torture.

But sure, sign us up to lecture other countries on their human rights abuses. Seems fine.

Australia’s been campaigning for a seat on the Human Rights Council since 2015, laughably describing ourselves as a “international human rights leader” with “a willingness to speak out against human rights violations and abuses”. Right from the get-go we’ve faced criticism from literally everyone (like, even North Korea and Iran) about our inhumane offshore detention policies. For a while, that criticism made it look like winning a seat would be tough, but France’s recent withdrawal from the race means Australia will be now be elected uncontested.

tip: flagrantly breach international law by detaining people in horrendous conditions so you, too, can get on UNHRC https://t.co/0XtSPEv1hm

— di frances (@di_f_w) October 15, 2017

https://t.co/5ZKbWUWZYL What a wretched body this must be if Australia is one of the better contenders.

— Ming The Merciless (@MGliksmanMDPhD) October 15, 2017

Lest we forget Rape & Torture in Australian detention centres#Australia to be elected to powerful UN HR council https://t.co/iGWrStQETR pic.twitter.com/kLjKKrYYTU

— #sanctionAustralia (@riserefugee) October 14, 2017

We won’t be the only member of the 47-seat council with a sketchy track record. The Democratic Republic of the Congo is going for a seat this week, despite its extensive and well-documented human rights abuses. Current members of the council include the Philippines and Saudi Arabia, both of which are currently facing criticism for extrajudicial killings.

That doesn’t make our human rights abuses less egregious though, and now’s as good a time as ever to point out that yet again, Australia is doing a lot of appalling shit we desperately need to change.

The Australian NGO Coalition Submission to the UN Human Rights Committee, prepared in September this year, is a very, very detailed look at Australia’s human rights failings. The report opens by listing a handful of Australia’s human rights improvements since its last review in 2009, before rolling on to an even longer list of things we’ve failed to do since then (e.g. provide reparations to the Stolen Generations), and an even longer list of areas in which Australia has “clearly gone backwards” on human rights.

Here’s a small sample of the problems the 84-page report highlights:

- Our boat turnback and offshore detention policies, which breach international law (we have a non-refoulement obligation to not send refugees back to countries in which they’re in danger).

- Our failure to address rates of violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, who are 45 times more likely to experience family violence than non-Indigenous women, and 10 times more likely to die from violent assault.

- Our “excessive police powers to lock people up”, including paperless arrest laws in the Northern Territory which are disproportionately used to imprison Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people for trivial offences.

- Our appallingly high numbers of Indigenous deaths in custody — the report notes that despite over 200 Indigenous deaths in custody from 1980-2013, no police officer has ever been convicted in relation to Indigenous deaths in custody.

- Our failure to ban forced medical interventions on intersex people (irreversible surgeries performed to “normalise” the genitalia of intersex children before they’re old enough to consent, which “if conducted without an evidence-based therapeutic purpose, evidence of necessity, and the consent of the patient they may constitute torture or ill-treatment, and medical experimentation”).

- Our failure to legislate for marriage equality.

- Our “extreme” metadata retention laws, which undermine rights to privacy by allowing law enforcement to access data without a warrant.

A coalition of NGOs will be briefing the UN on this report and Australia’s failings this week, though that briefing is unlikely to stand in the way of Australia simultaneously being elected to the Council (more than half the voting countries would have to refuse to vote for us to lose the spot).

That report does include a handy list of recommendations as to what we need to do to clean up our act though. We can only hope the government actually reads it.

–

Feature image by Louise Coghill, used under CC BY-SA 2.0 licence.