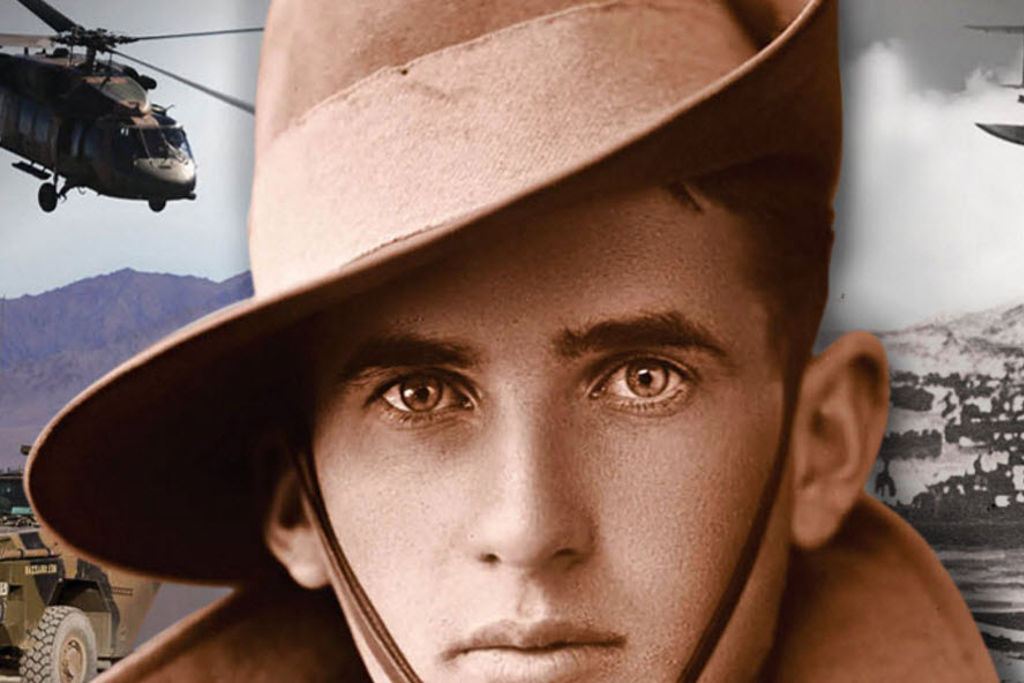

Every Anzac Day, Australia Commemorates War While Ignoring A Genocide That Killed Millions

Yes we forget.

Every April 25, Australia stops. In a time when debate over January 26 is more heated than ever, Anzac Day is the closest thing Australia has to a bona fide national day. We spent more than $300 million on centenary commemorations in 2015, and any perceived critique of the day’s sacrosanct status meets with severe backlash.

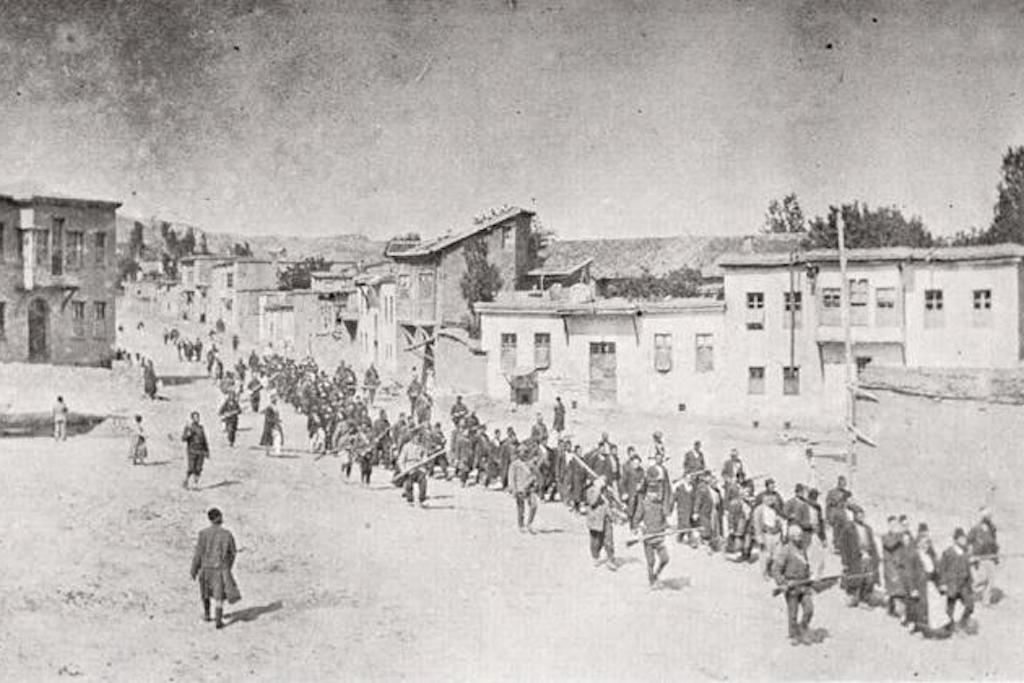

Every April 24, Australia’s Armenian community marks a very different milestone. The day before Australian troops stormed Gallipoli’s beaches in 1915, hundreds of Armenian community leaders and intellectuals were arrested in Constantinople and deported to holding centres. Many were later killed. ‘Red Sunday’, as it came to be known, marked the beginning of the systematic extermination of up to 1.5 million Armenians, Pontic Greeks, Assyrian Christians and others by the Ottoman Empire.

Armenian Australians have long pressured Australia to formally recognise the Armenian genocide, and received support from senior politicians and state parliaments. But Anzac Day’s central place in the Australian psyche – and the leverage it gifts a Turkish government implacably opposed to any recognition of the Ottoman Empire’s crimes – has frustrated their efforts.

Don’t Mention The War

Ironically, Gallipoli underpins decades of friendly relations between Australia and Turkey. Both nations view it as a formative episode in their respective histories. Mustafa Kemal, the founder of modern Turkey, commanded Ottoman troops during several of the campaign’s pivotal battles. Tens of thousands of Australians who travel to Gallipoli each year provide a boost to the local economy, and Australian Prime Ministers regularly give Anzac Day speeches from Gallipoli’s historic battlefields.

This partly explains why Australia’s official position on the Armenian Genocide is at odds with those of the International Association of Genocide Scholars, the United Nations, the European Parliament, Pope Francis, and 29 countries.

In a 2014 letter to the Australian Turkish Advocacy Alliance, foreign minister Julie Bishop said that while “the Australian Government acknowledges the devastating effects which the tragic events at the end of the Ottoman Empire have had on later generations and on their identity, heritage and culture … we do not, however, recognise these events as ‘genocide’”.

The Turkish government has a long and successful history of pressuring other countries not to recognise the genocide. In 2008, Barack Obama promised the United States would officially acknowledge the genocide if he won the presidency. When he left office eight years later, that promise remained unfulfilled. The European Union’s strong stance on the genocide has seen Turkey distance itself from the EU.

Whenever Australian recognition of the genocide becomes a likely prospect, the Turkish government uses Gallipoli as a weapon to coerce our politicians into silence. In 2013, Turkey threatened to ban members of New South Wales’ state parliament from attending Anzac Day centenary services, after the parliament unanimously passed a motion recognising the genocide. Then-Turkish foreign minister Ahmet Davutoglu said MPs would be denied visas if they tried to travel to Gallipoli, accusing them of trying “to damage the spirit of Gallipoli”.

The threat of Turkey acting against Anzac Day has deterred many Australian politicians from pursuing formal recognition of the genocide, especially once in government. In a speech to Parliament in 2011, Malcolm Turnbull called the genocide “one of the great crimes against humanity”. As Prime Minister, Turnbull has gone quiet on the subject. Former prime minister Tony Abbott, who once marked every April 24 with a statement of remembrance, declined to send a government representative to Red Sunday commemorations in Yerevan, Armenia’s capital, in 2015.

Even politicians of Armenian heritage have been unable to break Turkey’s gag. Joe Hockey, Australia’s current ambassador to the United States and our Treasurer between 2013 and 2015, is of Armenian descent, and urged Australia to formally recognise the genocide throughout his political career. Hockey was barred from speaking at a 100th anniversary commemoration of Red Sunday in 2015, shortly after Abbott held bilateral talks with Davutoglu, then Turkey’s Prime Minister.

Today marks 94 years since the Armenian genocide. For those of us with Armenian heritage we pause to remember the 1.5 million who perished.

— Joe Hockey (@JoeHockey) April 24, 2009

NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian, the granddaughter of Armenian genocide survivors, gave Gallipoli a wide berth in 2015, commemorating Red Sunday in Yerevan instead.

The Battle For Recognition

Armenian National Committee executive director Haig Kayserian says Turkish lobbying is “one of the big obstacles we face” in convincing Australian politicians to follow their convictions. Despite government backbenchers like Julian Leeser, Jason Falinski, Craig Kelly, Trent Zimmerman and Tim Wilson publicly stating their support for recognition, the ANC have difficulty in persuading more senior politicians to go against official government policy.

“A lot of politicians are very vocal on human rights in opposition, but that changes when they get into government. When you’ve got the foreign minister coming down on you like a ton of bricks, you start to weigh up the risks of speaking out”, Kayserian says.

Nonetheless, Kayserian is optimistic that momentum is shifting toward recognition.

“The ANC has been meeting people on all sides of politics for years, and there’s not been a single politician who’s disputed the facts of the genocide”, he says. “Instead, someone will say ‘I have 15,000 Turkish Australians in my electorate’, or the Anzac issue will come up. If an Australian government overcame those diplomatic and bureaucratic hurdles, the numbers are there. They’re there today, they were there yesterday, they’ll be there tomorrow.”

“It’s not acceptable for any civilised nation to allow the use of human rights as a bargaining chip. We had Gough Whitlam not allowing a segregated South African rugby team to tour Australia in the ‘70s. We had Malcolm Fraser stand up to Margaret Thatcher and visit Nelson Mandela in jail. We need that sort of backbone now.”

—

Alex McKinnon is a freelance writer based in Sydney, and a former editor of Junkee and the Star Observer.