Hating Anne Hathaway: How ‘Colossal’ Has Ignited Debate About Powerful Women

This movie about Godzille Anne Hathaway is deeper than you might think.

Imagine you woke up one morning and you were Godzilla. You’d still be you — same friends, same job, same problems — only now, once a day, your frustrations would be unleashed on the unfortunate populace of Japan. That’s the premise of Nacho Vigalondo’s Colossal (except it’s definitely not Godzilla, nor even in Japan, for finicky legal reasons), in which Anne Hathaway’s Gloria finds herself mysteriously controlling a kaijū wreaking havoc upon South Korea.

That premise makes for an incredibly unconventional monster movie. But even more so than you’d expect! Sure, there aren’t too many monster movies that could be accurately likened to a Joe Swanberg indie movie; there are more scenes here of Gloria hanging at a bar owned by her old friend Oscar (Jason Sudeikis) than of behemoths tearing down skyscrapers.

What sets Colossal apart is how it takes a conceit that could’ve easily made for a power fantasy and twists it into a disempowerment story, with Gloria’s newfound abilities proving a terrible liability. The film’s blackly comedic tone — it’s not a “comedy”, whatever you’ve heard, though it is funny — sours as it transforms into a dark allegory of abuse, alcoholism and misogyny.

Anne Hathaway, Queen of the Monsters!

Had Colossal been written with a male lead, I suspect it would have resembled the superhero power fantasies so popular in Hollywood. One of the film’s poster taglines — “All She Could Do Was Save The World” — even (falsely) promises that kind of film. It promises something familiar. Vigalondo isn’t known for familiarity though. His filmography is defined by intricate, unique experiments like Timecrimes and Open Windows: idiosyncratic genre films that don’t fit into any one genre. It’s important that Colossal doesn’t have a male hero. It has Anne Hathaway — and that’s why it (mostly) works.

Hathaway plays against type in the role. She’s a loser. Not a loser like in The Devil Wears Prada, where her apparent ineptitude is just a cutesy veneer for enthusiasm and raw talent. No, an actual loser; one with messy hair and a drinking problem who begins the film getting dumped by her boyfriend (Dan Stevens, playing the beauty to Hathaway’s beast). The monster appears to be a projection of sorts of an emotional crisis resulting from that breakup (and its associated issues, like needing to squat in her parents’ uninhabited house after getting kicked out of her now-ex-boyfriend’s apartment). Hathaway is excellent in the role, smoothing out her usual intensity with an endearing hangdog vibe.

Critics have been quick to align her on-screen role with her reception off-screen — a reception that, particularly in the wake of her Les Mis Oscar win, has been decidedly frosty over the last few years. Colossal, apparently, represents — or deserves to represent — a thawing of public opinion. Colossal “Just Made Anne Hathaway Cool Again”.

According to recent press, Hathaway is now likeable; it’s no longer cool to hate her! The film’s “a welcome reminder of what a good actress [she] can be, except that some of us never forgot in the first place.” The Ringer argues that Colossal is leveraging its lead actress’ extratextual baggage; Vogue veers off into a tangent about Hillary and Trump, because this is 2017, after all.

Hey media, this is my answer.

Sincerely

An Anne Hathaway fan. pic.twitter.com/67q8BnDSpJ— Anne Hathaway (@AHathawayNews) April 6, 2017

Why is this narrative so intoxicatingly enticing for today’s film critics? In part because it’s a convenient hook — hey, I’m using it! — but it’s also illustrative of our expectations of the narratives we expect around actresses and (yes, Vogue) powerful women in general. Powerful women, it seem, need a redemptive narrative to be respected. Everyone, apparently, was a Hatha-hater when she was an earnest, talented actresses winning accolades left and right. But now that she’s suffered through adversity (read: you and your friends disliking her), she’s deserving of newfound acclaim.

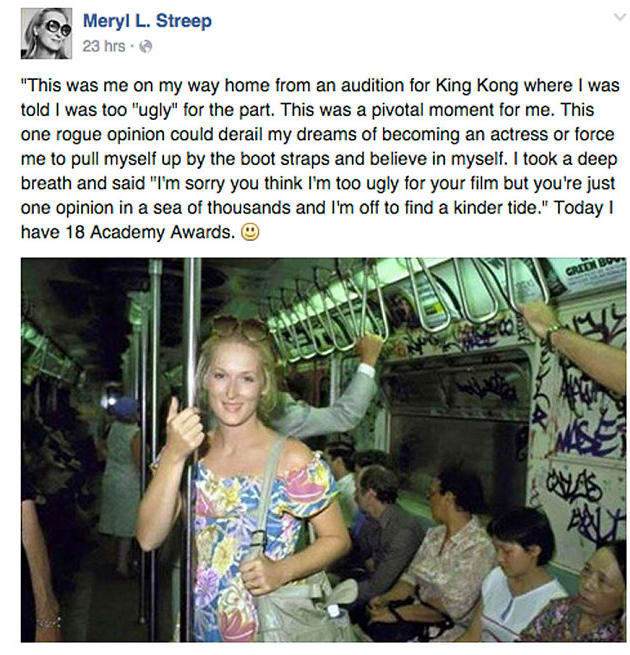

This isn’t a corner case. While their male counterparts earn enduring respect off the back of a small number of roles, it seems we need actresses to continually prove themselves. Think about the narrative around Nicole Kidman’s superlative work on Big Little Lies — rather than simply celebrating the quality of her work, it’s been framed as a revelation from an oft-dismissed actress (as discussed in Anne Helen Petersen’s extensive profile, ‘How Many Times Does Nicole Kidman Have To Prove Herself?‘). Even Everyone’s Favourite Actress Meryl Streep had a (fictitious) Facebook post about her overcoming adversity early in her career go viral.

The popularity of posts like this suggests a hunger for these stories. We want stories of successful women couched in failure and difficulty and recovery; stories that give us permission to like these women, who are more successful than we could ever hope to be.

You sometimes see these narratives take hold for men — remember the “McConaissance”? — but they’re outliers compared to their ubiquity for women. These stories aren’t necessarily ill-intentioned, particularly if they acknowledge the disproportionately difficult path women must follow to achieve success. Still, they imply that within our society, the power obtained by powerful women is a double-edged sword: something that needs to justified and qualified to be fully accepted. And in an insidious — and possibly unintentional — way, that’s the story that Colossal is telling.

A Disempowerment Fantasy

Almost immediately, Gloria’s uninvited connection to the kaijū devastating Seoul becomes a liability. Oh, sure, she has a bit of fun showing off her powers to her new barfly friends (Sudeikis is joined by the grizzly Tim Blake Nelson and ditzy Austin Stowell), but she also has to live with the understanding that — intentionally or otherwise — she’s caused the deaths of many people. (A thread that remains perplexingly unexamined throughout; the populace of South Korea are never developed beyond a throng of nameless victims.)

Gloria tries to do the right thing as legally-not-Godzilla; she carefully plots out how her physical space maps to the streets of Seoul to ensure that she causes no more collateral damage. If that were all there was to Colossal, it’d probably only make for a memorable short film. Local Woman Discovers Amazing Powers, Must Carefully Police Her Actions To Avoid Hurting Others. There’s some subtext there about how powerful women are expected to be considerate of others in a way that men are not, but not enough to justify feature length.

Enter the men in Gloria’s life. Her ex, Tim, returns and is quickly established as a manipulative cad who’d expected that the break up would draw her back into his arms, more dependent than ever. Much like the narratives we construct around actresses, he tears her down while intending to build her back up to be more ‘likeable’, respectful, recognisant of her place. He’s not interested in allowing her to rebuild her life — he wants her by his side, a little more broken than before. But Tim is small fries compared to the mounting of influence of Sudeikis’ character, Oscar, who transforms from ally to abuser with terrifying swiftness.

To elaborate further would probably constitute spoilers. Suffice to say that Vigalondo’s screenplay isn’t afraid of following its storyline down a very dark path. Gloria’s ‘powers’ are stripped of their power entirely, becoming a tool with which she can be leveraged. This suggests the paralysing effect of addictions — specifically, alcoholism — but it’s also demonstrative of how differently we treat powerful men and powerful women.

Where men’s achievements and abilities are valorised, women are expected to apologise for their success, to emphasise their failings (even if those failings are little more than unapologetic ambition). Colossal recognises that we see successful women — whether accepting Oscars or stomping around Korea — as monsters.

Yes, it’s time to stop hating Anne Hathaway. But it’s also time to reflect on why we hated her in the first place.

–

Colossal is in cinemas now.

–

Dave Crewe is a Brisbane-based teacher and freelance film critic who spends way too much of his time watching movies. Read his stuff at ccpopculture or pester him at @dacrewe.