Andy Bull On David Lynch, Paul Auster, And His Pop Culture Picks

The Sydney artist's second album, Sea Of Approval, is out now. We asked him for moments in pop culture that have inspired him the most.

‘Pop Culture Picks’ is a (semi-)regular feature, where we ask interesting people for their inspirations — authors, films, websites, albums, events, people, whatever. For more instalments, click here.

–

It’s been five years since Andy Bull released his debut album, We’re Too Young. Five years is a long time between drinks — but judging by the Sydney artist’s follow-up, his time wasn’t idly spent.

Released earlier this month, Sea of Approval manages to be both personal and expansive, packed with drama, sonic trickery, and emotive pop — but never sounding dense for the sake of density. Sexed-up bedroom jams about self-doubt and longing make room for piano breaks and drum machines; classic ballads and pop songs balloon out to waves of ethereal, intergalactic synths. Theatrical interludes separate shifts in mood and genre, heart and heat, as Bull looks as much back to the ’80s as he does to the future of pop. In fact the self-produced album is crammed with so many sonic references that we were curious about the inspirations behind it — so we asked the artist to write about pop cultural moments that have most affected him.

“I’ve been charged me with the task of writing about some of my favourite things,” Andy Bull wrote back. “It feels a little like being given an exam paper that has no question or hypothesis at the top; just the word discuss.

“But skimming through recent memories, here are four different things that felt significant at the time and have perhaps have informed my own thinking since.”

–

An author: Paul Auster

Andy Bull: Sometimes, when I’m in the middle of a dream, I get this sense that I have dreamt that dream before; there’s some sort of cue, maybe an object or a sensation that, within the dream, triggers déjà vu with the kind of intensity that you can only know while wading around the murk of your subconscious. I get a kind of feeling like “everything is connected, I see it, I’ve seen it all before, it all makes sense now”, and then I wake, left reaching lamely out for whatever the understanding was as it inevitably drains away, and I’m back, dumb and dry-mouthed in my bed, primed to smash ham-fisted through another day on earth.

Read Paul Auster’s books, and you’ll come as close as ever to knowing this sort of feeling in your waking hours. They often start out like pulp crime novels, but thread by thread mutate into something else altogether. Identities merge — yours, his, the protagonists within this book and across others — and what begins as a kind of satisfyingly familiar literary noir ends up turning inside out and dropping deep into the psychic soup pot as traditional literary structure apparently collapses.

Read a few of his books if your going to read any, because a sort of thematic trajectory will reveal itself, if you can put your finger on it. And check out The Winter Journal, his first memoir, because it frames and contains the seeds of much of his fiction.

–

A film: Mullholland Drive, dir. David Lynch

Andy Bull: I actually think that this was the first David Lynch film I ever saw, although it seemed strangely familiar to me at the time. This film impressed me with a feeling that my senses were no longer mine, or at least I couldn’t trust them.

Crucially, I reckon, the takeaway from this film was not its plot or dialogue, but its very distinct mood, its rejection of chronological logic in favour of symbolism and wordless feeling, feeling which seemed to colour everything about it. I think I see this as significant because it made me wonder if I could teach myself to think of music in the same way — less didactically and more cinematically; even, or perhaps especially, when the expected logic or structure of a story seems askew.

Watching Lynch and reading Auster are experiences that have some things in common, actually. Even outside of the creative process, there is something important to be gleaned from Lynch; to me, it’s the awareness that beneath the gloss and sheen of normality and daily life lies a unseen substrata of obsessions, darkness and horror.

–

A gig: Jack Ladder and The Dream Landers

Andy Bull: In 2011, Jack Ladder had a three-week residency at the Beach Rd Hotel in Bondi. Entry was free. It wasn’t a hyped thing. I went along one night with my housemate to a respectably attended show, and was so impressed by what I saw that I returned the next two weeks as well.

I’d known of Jack Ladder previously from his album Love Is Gone, which I’d thought of as a superior work of its kind — ‘Barber’s Son’ had one of the best lyrics going around at the time, I reckon. What he and the Dream Landers were serving up at this residency, though, was something else altogether; live renditions of what would become the (bewilderingly ambivalently received) album Hurstville.

These were sweeping, thundering, bleak and unforgiving arrangements of songs, with lyrics that described a kind of imminent personal apocalypse. The apparent mundanity of words like “I’ll flip the burgers and you work the till” and “I dug my own grave just standing still” gave me the a palpable sense of a man who had toed the line of an emotional event horizon, submitted, and collapsed into infinite coldness. And yet there was so much power in it all, it was somehow redemptive at the same time. I’d never heard anything quite like it.

Kirin J Callinan was playing guitar in the band for those shows, and since that time I’ve come to know him; recently I mentioned to him how moved I was at those shows. Kirin agreed: “Those shows felt seminal”. They certainly were formative for me; what I saw was a band wrangling more raw power up there on stage than I had ever come close to summoning myself. It was very inspiring.

–

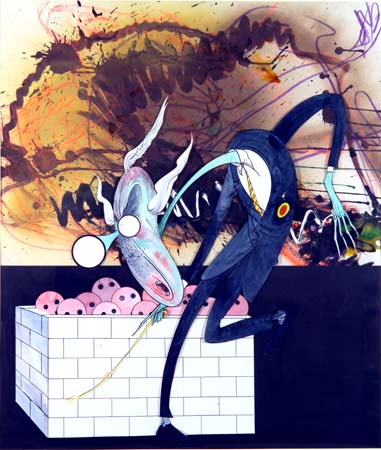

An illustrator: Gerald Scarfe

Andy Bull: When I was seven or eight years old, my dad returned from a few months working overseas with a bag full of gifts for my brothers and I. He’d been working at a hospital Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, and the gifts consisted of two kinds of items: the first was free T-shirts printed with Operation Desert Storm propaganda, left over from the Gulf War. Mine had a cartoon of a fighter jet, a mushroom cloud, and the words “Good Night Saddam!!” across the top; fittingly, it would become my pajama top for the next year or two. Good night Saddam, and good night everybody!

The other kind of item delivered by this errant Saint Nick was pirated cassette tapes. The cassettes were labeled Moby Disc and Hang Ten, rather than, say, Capitol or Columbia, and included tell-tale spelling mistakes and the odd sequencing error. Side A would end abruptly midway through a song, and Side B would pick it up again casually as if it were no big deal. My older brothers and I scrambled over the pile, and I, being seven, grabbed the one that I thought had the best cover art, which happened to be Pink Floyd’s The Wall. I suppose if you’re going to own just one cassette tape, it might as well be an epic, 27-track prog-rock concept album with an accompanying film.

–

–

Of course, the music was way over the top, but at that age it just seemed so immense and immersive and awe-inspiring. The lyrics introduced me to some bleak ideas: war, nationalism, drugs, racism, bombs, domestic abuse, and needless to say, they had me asking a few questions. I was prompted by all this to write the first song of my own, which was really just a Frankenstein-job of Wall songs with some of the words changed.

Crucially in amongst all this was the fact that the aforementioned album artwork and, later, the film’s incredible, terrifying animation sequences, were illustrated by a guy named Gerald Scarfe. I was a mad keen drawer as a kid — for a long time I thought that’s what I would grow up to do — and Gerald Scarfe’s drawings really got to me. Being that young, the significance of every new sound and vision seems enormous, I guess because there is no precedent for them and your young brain has to really jump up and organise itself around the event. Still, if you look at what Scarfe does, it’s not hard to imagine having a strong reaction to it; it’s visceral, bold and grotesque.

Like H.R. Giger’s Alien, or say, the slimy clump of what? that blocks the shower drain, Scarfe’s illustrations seem to have been put together out of the tangled, aberrant stuff that you forgot about, or have denied. Aberrant feels like the operative word here, in that these tangled psychic clumps are not so easily separated; it reminds me of the lyric to Laurie Anderson’s ‘O Superman’; like Scarfe, she draws from a murky place where logic dissolves and the Personal and Political, Savior, Tyrant, Mother, Nation and Chemical Bomb all bleed into one another. History is complex and the world is messy.

It’s potent stuff on an academic level, and its immediate stuff on an aesthetic one.

Later, in my teens, I would read Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and mistake Ralph Steadman (also English, also born 1936) for Scarfe. The two do have, at a glance, aesthetic similarities, but pan out a little further and you can see a longer tradition at work from which they take their cues. Dadaism, Expressionism, and much of what the National Socialists would call ‘Degenerate Art’ pre-WWII, and then perhaps post-war artists like Francis Bacon would leave a trail for them both — but maybe particularly Scarfe, whose living would come from political cartooning. Check out Otto Dix’s Der Krieg cycle and you’ll see how Scarfe could be said to have pulled threads of degeneracy into the Cold War world of British newspapers. That’s the role of the cartoonist I’d wager, to literally illustrate what is perverse, and in this way it’s not the artist who is degenerate but rather the object illustrated. Perhaps this is why we continue to call it by the National Socialist label: because it turns out that it’s is a good name, with ironic truth.

The last thing I’ll say here about it is this; when I was a boy and I looked at these pictures, I assumed they illustrated a world of horror and strangeness that had ended long ago, or at least was far away enough to not be of consequence to me, even as I slept soundly in my Goodnight Saddam! T-Shirt. I suspect however, that like the muddled objects of degenerate art, the world remains violently tangled as ever.

–

Andy Bull’s Sea Of Approval is out now.

–

ANDY BULL NATIONAL TOUR

Brisbane: Sunday September 7 @ Spiegeltent — tickets here

Canberra: Thursday September 11 @ Transit Bar — tickets here

Newcastle: Friday September 12 @ Cambridge Hotel — tickets here

Sydney: Saturday September 13 @ The Metro — tickets here

Adelaide: Thursday September 18 @ Jive — tickets here

Perth: Friday September 19 @ The Bakery — tickets here

Rottnest Island, WA: Saturday September 20 @ Rottofest — tickets here

Hobart: Friday September 26 @ Waratah Hotel — tickets here

Melbourne: Saturday September 27 (sold out) & Sunday September 28 @ Corner Hotel — tickets here