Alex Cameron, Kirin J Callinan And The Problem With “Ironic” Toxic Masculinity

This joke isn't funny anymore.

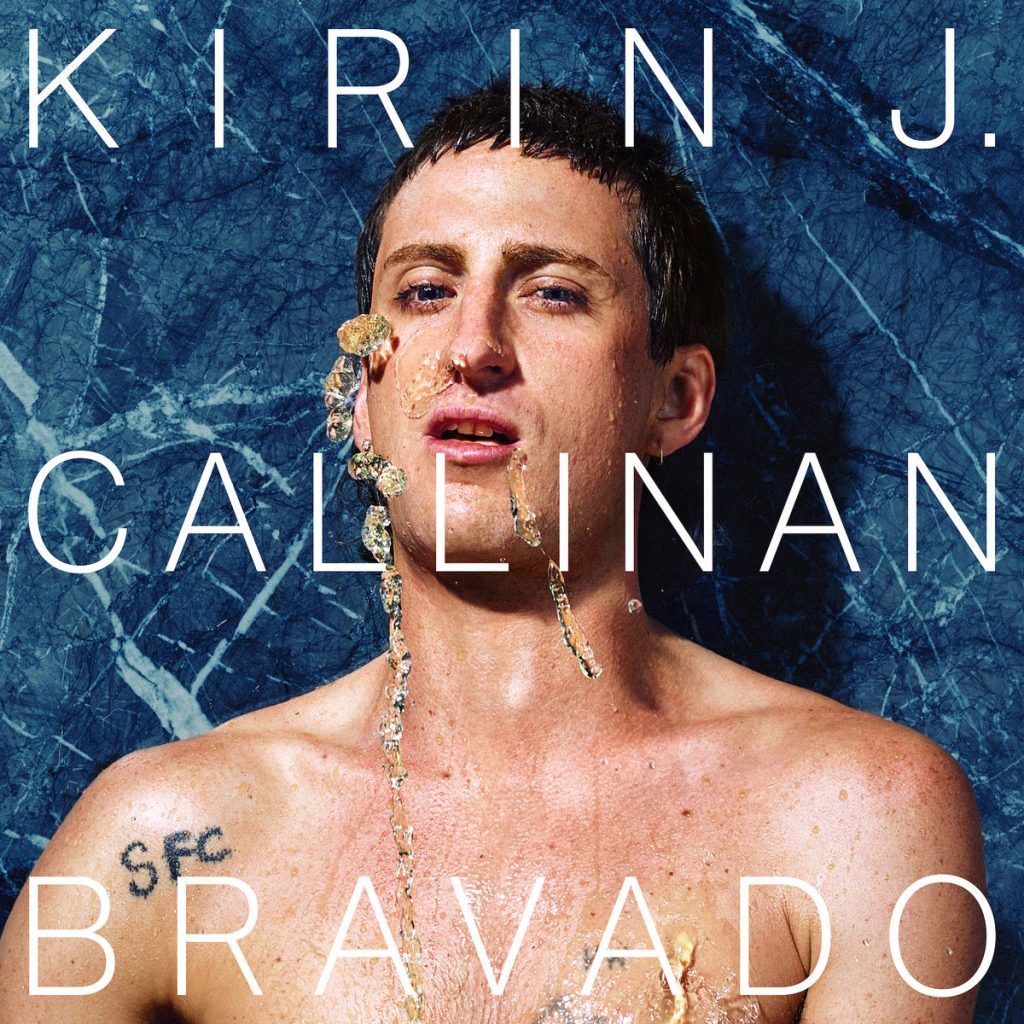

On his second album Bravado, Kirin J Callinan takes the piss. No, literally: on the album cover, Kirin takes aim at himself, the stream mid-air, just about to hit his face. Just don’t call it a joke.

“I think the record is deeply funny,” he told SBS Viceland earlier this year. “[But] just because something’s funny doesn’t mean it’s a joke. I’m deadly serious about it.”

Kirin repeats this sentiment a lot in interviews, as have fellow Australian acts Client Liaison and Alex Cameron. They all provoke the question, adopting the poses and images of Australia’s ocker past, poking holes in its legacy.

Kirin’s first album, Embracism, has him howl about toxic masculinity in a heavy accent reminiscent of late-night RSL sing-a-longs; Alex Cameron sings in character as a washed-up battler who mistreats women and himself; and Client Liaison’s early ‘90s corporate aesthetic-driven synth-pop is so gleefully vacuous that the duo is basically the pop star version of American Psycho.

And we love it. Each artist has had a massive year: both Bravado and Alex’s sophomore album Forced Witness released to international critical acclaim. Meanwhile, Client Liaison have built off last year’s debut album Diplomatic Immunity with headline-grabbing, high-production live shows, including the jaw-dropping Tina Arena cameo during their Splendour in the Grass set.

We laugh, too. It’s all abrasively tongue-in-cheek, an inflated version of a world we already know. That, of course, is the idea.

PISS.

It’d be hard to take these acts at face value. Even on aesthetics, Kirin’s melodramatic music videos and mullet, Client Liaison’s inflatable Foster cans and Alex Cameron’s speed dealer sunglasses alone let us know there’s irony at play.

And that’s before you listen to songs like ‘StudMuffin69’, where Alex croons about chatting up a 17-year-old girl online. It’s grossly funny, with a purpose.

“I know people’s first reaction will be to laugh and the second to wonder exactly what they laughed at,” Alex Cameron told Loud & Quiet. “Eventually they will realise they laughed because they liked it and it was true and it made them feel something.”

But are we laughing at these characters or egging them on? And do these acts benefit from these masculine personas more than they critique them? Sometimes, it’s a little too much of a pissing contest to tell.

Artistic Immunity

To their credit, the discomfort we can experience with these acts — particularly Kirin and Alex, whose lyrics are much more pointed — is part of their power. Teetering the line of nostalgia, they indulge the draw of ’80s and ’90s Australian rock while acknowledging the sexist, homophobic and racist roots of our masculinity-worshipping culture.

And while all three acts swear sincerity, there’s an undeniable cloud of irony over everything they do.

“We like using the word ‘absurd’,” Client Liaison member Harvey Miller told The Saturday Paper late last year. “We like absurdity. Les Patterson is a big hero of ours. It’s absurd; it’s theatre.”

“When we create an idea we’re like, ‘Yes, we’ll get a limousine, and we’ll drive around’ — and two weeks later we’re dead serious and onto the next thing,” said Harvey. “So we’re actually living it… The line blurs. We like to imagine something and realise the fantasy.”

When the line blurs, intent is lost but results remain. If the fantasy becomes reality, isn’t it just two guys buying a limo because they can?

And where does critiquing an alpha male’s need for constant attention sit if you’re continuously showing the world your own dick, à la the omni-naked Kirin J Callinan? What about Alex’s ‘The Chihuahua’, a forlorn love song where an ex-lover is only known as “The Pussy” to reveal how men continue to treat women as sexual objects first, people second?

It’s easy to dismiss criticism when everything’s done with a wink. But it’s a delicate dance, one which too easily follows the steps of the past, treading on the toes of minorities in the way.

Was It All Bravado?

In the vinyl of Bravado, there’s a photo of a naked Kirin J Callinan painted head-to-toe brown, blending in with the leather lounge he’s reclining on. It’s blackface, frustratingly lazy and offensive in its lack of care. It’s a line Australians should know by now not to play with.

In June, Isabella Trimboli, co-founder and editor of Gusher Magazine — an Australian print music journal written solely by women and non-binary contributors — called the image out on Twitter. It received little attention elsewhere.

Speaking to Junkee, Isabella elaborated on why she finds this ironic posturing troubling. “There is a long history of women, people of colour, and queer people using humour to make a mockery out of systems of oppression that hurt them,” she said.

“So when straight, cis men co-opt the joke and have their whole shtick be some grotesque masquerade of masculinity, the joke just isn’t funny anymore. Instead of critically mocking the privilege men have in society, it just feels like they’re rubbing it in. Embracing sexist or racist language and imagery is not the same as interrogating or subverting it.”

And yet, she says, “these men are the ones that are praised for their self-awareness and insightful cultural critique as if they’re the first ones to lift the lid on how toxic masculinity can be.”

It’s an idea which covers the discomfort in Client Liaison playing the didgeridoo during live shows, a well-intentioned moment that contextually comes off as more kitsch than genuine.

Or Alex Cameron’s unnecessary in-character use of the slur “faggot” repeatedly on Forced Witness track “Marlon Brando”. Towards the end of the song, the character half-heartedly apologises for the slur — by using it again.

Speaking to FlavourWire, Alex defended his use of the word:

“I feel challenged by that song, still — it’s about people that, if I could flick a button, ideally wouldn’t exist,” says Alex. “But unfortunately they do; we’ve been confronted by them in Australia, and in our travels. I felt it’d be more irresponsible as a straight white man to not represent that, to not address it, to not challenge it in a song.”

Again, it’s a well-intentioned idea. It’s a clever portrait of males who refuse to do better, even when called out.

But the layers of irony don’t shield a queer listener from the impact of hearing a slur they’ve likely had hurled at them. It does, however, shield Alex. It’s a critique that doubles as a pat on the back, one which we as an audience we’re keen to join in on.

In the shield of irony, we’re given a little more distance than we deserve from Australia’s ingrained sexism, homophobia and racism. It’s easy to laugh, because we, The Smart Audience, get it.

In Pitchfork’s review of Forced Witness, they celebrate how the album “forces us to see, the most despicable thing about these bros isn’t that they’re total pigs — it’s that they know it and refuse to do anything about it.”

This is true, and a testament to Alex’s songwriting. But you could also ask anybody who isn’t a straight white male about their experiences, and they could tell you the same thing.

The difference is you’d know they aren’t taking the piss.

—

Jared Richards is a freelance writer and co-host of Sleepless In Sydney on FBi Radio.