A Wilder World: Hayao Miyazaki’s Unsung Masterpieces

The legendary animator behind Spirited Away and Princess Mononoke is planning to retire after the release of his new film. Here's a few of his lesser-known career highlights.

It’s a sad day for animation lovers, with news that the legendary Hayao Miyazaki plans to retire from filmmaking. Again.

Studio Ghibli head Koji Hoshino revealed the news during a press conference at Venice Film Festival overnight, ahead of the premiere of Miyazaki’s latest movie, The Wind Rises, about a boy who dreams of designing planes in pre-WW2 Japan. Miyazaki himself was not present, but is expected to make a statement himself next week from Tokyo.

Miyazaki’s career in animation stretches back nearly four decades, but he’s best-known for his work at Studio Ghibli, the animation house he co-founded in 1985. Ghibli’s films — specifically Miyazaki’s — have come to define Japanese animation for many outside the country. His body of work includes beloved titles like My Neighbour Totoro (1988), Princess Mononoke (1997), Howl’s Moving Castle (2004) and Ponyo (2008). The best-known of all may well be Spirited Away (2001), about a girl transported to a world of spirits and monsters.

This isn’t the first time that Miyazaki has called an end to his career; the filmmaker has announced his retirement twice before, the first time shortly after Princess Mononoke came out in 1997.

You’ll probably be seeing a million and one clips from Spirited Away and pictures of Totoro on your Facebook feed in the coming days, so in honour of his long and brilliant career, fans Alexander Tulett (AT) and Alasdair Duncan (AD) decided to look back at some of the lesser-known works of the Miyazaki and Ghibli canon.

They may not be among the best-known titles, but they’re essential elements of Ghibli’s animated magic. If you’ve worn out that DVD of Spirited Away, give one of these a try.

–

The Castle of Cagliostro (1979)

Miyazaki’s directorial debut is an absolute masterstroke, combining ingenious animation with genuinely funny dialogue and unforgettable set pieces. The story is part of a series starring Arsène Lupin III, master thief and utter goofball (as well as handy reference for Lupe Fiasco), written as the fictional grandson of the fictional French detective of the same name.

The plot set-up is relatively straightforward: after robbing a casino only to find the burgled cash to be counterfeit, Lupin — who recognises the counterfeits from his early criminal career — and his men track the source of the bills to a European country called Cagliostro. But this basic plot becomes irrelevant as soon as you witness the virtuosic car chase sequence that occurs almost immediately upon their arrival.

Steven Spielberg is often incorrectly attributed as saying that this is his favourite car chase scene in a movie. But while he may never have actually said this, it’s easy to believe it to be the truth. The way the action fills the frame so effortlessly is very reminiscent of the early-Hollywood action films that informed much of Spielberg’s work. It’s also a great indication of Miyazaki’s beautiful attention to visual detail, a trend that would continue throughout his entire filmography, and a big part of the reason that his fans fall so deeply in love with the movies he helps create. — AT

–

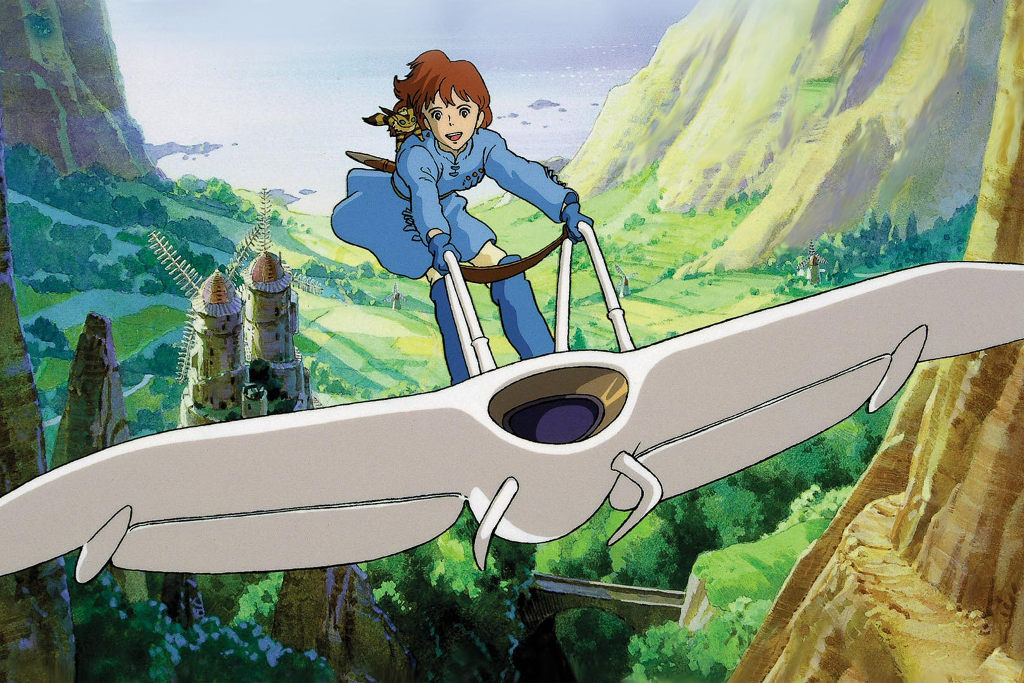

Nausicaä Of The Valley Of The Wind (1984)

Many of Miyazaki’s films are about children, and his young protagonists share a lot in common. They tend to be smart and wily, yet simultaneously naïve and a little bit needy. They may like to go off exploring mysterious worlds — like the forest at the bottom of Satsuki and Mei’s garden in My Neighbour Totoro, or the bathhouse of the spirits that Chihiro encounters in Spirited Away — but like real children, they still rely on the reassurance of home and family.

Nausicaä bucks this trend somewhat: its heroine is still a child, but by virtue of her circumstances, she’s forced to be self-sufficient, and carries the weight of the world on her shoulders.

The premise of Nausicaä Of The Valley Of The Wind is actually pretty scary. The cities of the world have all burned down in a great apocalyptic war, leaving behind great, toxic forests and tiny pockets of humanity. Nausicaä herself is a princess from the peaceful Valley Of The Wind. She travels frequently to the toxic jungle, attempting to find the source of the sickness that it spreads, and has even formed a bond with the Ohmu, the huge, feared insect creatures that live there. When war inevitably comes to her peaceful valley, she has to stand toe-to-toe with adults to prevent the destruction of everything she loves.

Nausicaä is a beautiful and sad movie, and one that doesn’t try to shield its child audiences from darkness, or even violence. Though it was released in 1984, before the founding of Studio Ghibli, it is generally regarded as being the first Ghibli film, setting the tone and style for Miyazaki’s later works at the studio. — AD

–

Porco Rosso (1992)

At the Ghibli Museum in Mitaka, there stands a recreation of Miyazaki’s study and work desk. Amongst the piles of paraphernalia, illustration equipment and boxes that litter the small space are a large quantity of photo books, both purchased and collated by Miyazaki. Mostly containing photographs of landscapes and architecture, these serve as inspiration for creating the hyper-real world that Ghibli films inhabit. These settings feel real because they’re obviously so rooted in reality, with the fantastical elements woven through subtly and seamlessly.

Porco Rosso is perhaps one of the least commonly celebrated Studio Ghibli films, despite containing some of the greatest characterisation and the most beautiful background scenery of any movies that Miyazaki was involved in. The film typifies the Ghibli universe method of combining the real with the unreal, and by the end of the film you’ll find it hard to believe that Porco Rosso wasn’t truly soaring over the Adriatic Sea.

The film also contains the line “A pig that doesn’t fly is just a pig”, which could either be the greatest assessment of the human condition in cinematic history, or one of the most brilliantly absurd thoughts uttered since the demise of Monty Python. Either way, undeniable genius. — AT

–

Miyazaki’s Legacy: Ni No Kuni — Wrath Of The White Witch (2013)

Hayao Miyazaki is rumoured to dislike video game adaptations of his work. 1983 saw the release of Cliff Hanger, an ill-fated arcade game that incorporated elements of The Castle of Cagliostro. Around the same time, a trio of indifferently-received Nausicaä games came out for home consoles. Following the releases, he refused to let any further works be adapted, meaning no platform-jumping Princess Mononoke or cell-shaded Spirited Away.

So it was quite a big deal when Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli announced plans to partner with RPG developer Level 5 on Ni No Kuni: Wrath Of The White Witch. Miyazaki’s actual involvement in the game was minimal, but his influence still hangs heavily over it.

Simply put, Ni No Kuni is one of the most stunningly beautiful titles ever to grace the Playstation 3. The game features many of the hallmarks of a typical Ghibli film, including a richly-detailed fantasy world, and a plucky young protagonist to explore it. The game tells the story of a young boy named Oliver, who is grieving the loss of his mother when his favourite toy comes to life and tells him that there may be a way to bring her back, by finding her ‘soulmate’ in a parallel world. In this world, Oliver fights and tames various monsters, makes new friends, and eventually becomes a hero; it’s a basic story that’s been told many times, but Ni No Kuni does it with poignancy and beauty.

Every corner of the world is impeccably designed, from the glittering glaciers to the haunted forests. In classic RPG fashion, the terrain opens up as you travel on foot, by ship, and eventually, swooping and soaring on the back of a trusty dragon called Tengri. If you’ve ever wanted to jump into a Ghibli film and explore the world at your own pace, Ni No Kuni gives you that chance. It’s an exceptional game, and we have Miyazaki’s legacy to thank for it. — AD

–

Alasdair Duncan is an author, freelance writer and video game-lover who has had work published in Crikey, The Drum, The Brag, Beat, Rip It Up, The Music Network, Rave Magazine and SameSame. You can find him on Twitter at @alasdairduncan.

Alexander Tulett presents Close To The Edge on FBi 94.5, plays bass for alt-pop band Maux Faux and DJs hip hop under the name Moranis. You can also find him on Twitter at @bombedatapollo.