A Guide To Australian Culture, As Told By A Manus Island Asylum Seeker

"We learn about Australian culture by watching the guards, so most of us have learned some swearing.”

“Growing up, I watched Skippy when I was a child,” says writer Behrouz Boochani. “I saw Australia the movie with Nicole Kidman too, that was okay. I enjoy listening to Kylie Minogue, especially Can’t Get You Out of My Head.”

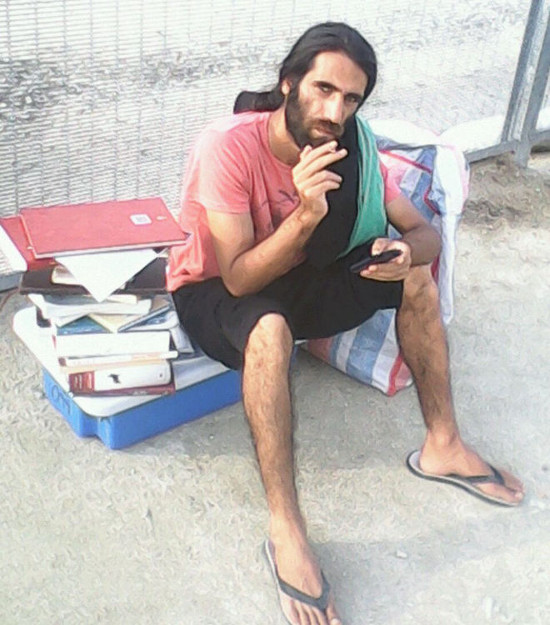

Picture Manus Island and chances are you think of a problematic detention centre. Its inhabitants depicted in grainy digital images of protests and riots, their faces rarely in mainstream media, their identities closely guarded and their ideas and thoughts even more so. But as people who grew up in countries with rich and proud cultural traditions, their knowledge of Australian culture is less well-known.

“They have not allowed us to know Australian culture here,” says Boochani, an Iranian Kurd soon to be entering his fourth year in detention. Both major party leaders have pledged that no detainees will settle in Australia. “They want us to learn about Papua New Guinea. We learn about Australian culture by watching the guards, IHMS, Broadspectrum and other Australians who work in this prison, so most of us have learned some swearing.”

Unlike most 32 year-olds who spend a lot of their time writing, Boochani isn’t clinging to the music of his youth or trying to stay on top of what other people in his chosen culture are doing. In fact, his listening habits are more likely to resemble those of someone twice his age.

“I listen to a lot of classical music,” he explains. “Especially Mozart and Beethoven. It’s perfect music for a place like Manus. I can endure the long queues listening to this kind of music. When I protested by sitting at the top a tree for ten hours I listened to Vivaldi’s Four Seasons. I also sometimes listen to Kurdish traditional music.”

Boochani grew up in Kurdish Iran, a place he left in July 2013 after publishing a series of popular articles pushing for Kurdish cultural freedom. The impression most Iranians had of Australia was a very positive one: a liberal democracy that created bright and buoyant cultural exports.

Like a lot of detainees, Boochani fled a government that operated, as he explains it, “a big propaganda system against western civilisation and values. It’s hard for Iranians to know what is going on in western countries, and what information we get is true.”

It is similar on Manus Island. A lot of information takes the form of gossip, rumours and people reporting translations of second or third hand news.

“My greeting here is ‘What’s news Behrouz? What’s happening in Australia?’” he says. “Everyone here knows Peter Dutton, Malcolm Turnbull, Scott Morrison, Sarah Hanson Young and Bill Shorten. People know them very well. We get our news from the internet and read articles from newspapers and websites in our countries and from Australia.”

While the detainees on Manus Island have been shown to be very responsive to political events in Canberra, mobilising protests against government announcements within hours of their broadcast, the art they create is less reflexive. Boochani is also interested in what motivates those detainees able to express themselves (some of whose artwork can be seen in the background of the video below) and the writers at work in the detention centre.

“They did not allow to us to listen to music for the first six months,” he says. “They confiscated our property so we could not access our music. But music has been something that has been important to many people.

“Writing and art here is coming from suffering. To survive people feel they have to write and create something. Some people are even writing for the first time. Some people make art through painting or drawing. Some people play music.”

The organisation Writing Through Fences is collating the work of people in Australia’s detention centres. As well as providing insight into personal experiences, the material collected is providing researchers and academics with insight into art made under stress.

“The media has written a lot, film makers have made films and politicians have talked a lot about it but I don’t think any of them can describe the reality of Manus,” says Boochani, whose first book in English has been written on Manus and is due out later this year.

“I write from inside the experience of being a political prisoner here as well as a writer. I try to describe how people feel under torture, how a father feels in a prison, how people are when they think about suicide. I write about the small things that add up to make this prison as well as people: stories, nature, what I observe. What I see through my eyes as an imprisoned writer.

“I feel that I am working for Australian history by writing this book. I will tell a part of Australia’s history and I hope I will be successful in my mission. Literature is a language of life.”

–

Andy Hazel is a freelance journalist based in Melbourne who works at The Saturday Paper.